Fiancee wants to solve mystery of Border Patrol agent’s death

- Share via

Reporting from Houston — When Angela Ochoa arrived at her fiance’s hospital bed, he was unconscious.

“He had cuts to his hands, swelling to his face, to his abdomen. He obviously had to have put up a fight,” Ochoa said.

But no one could tell her what had happened. Later that day, Nov. 19, Border Patrol Agent Rogelio “Roger” Martinez died.

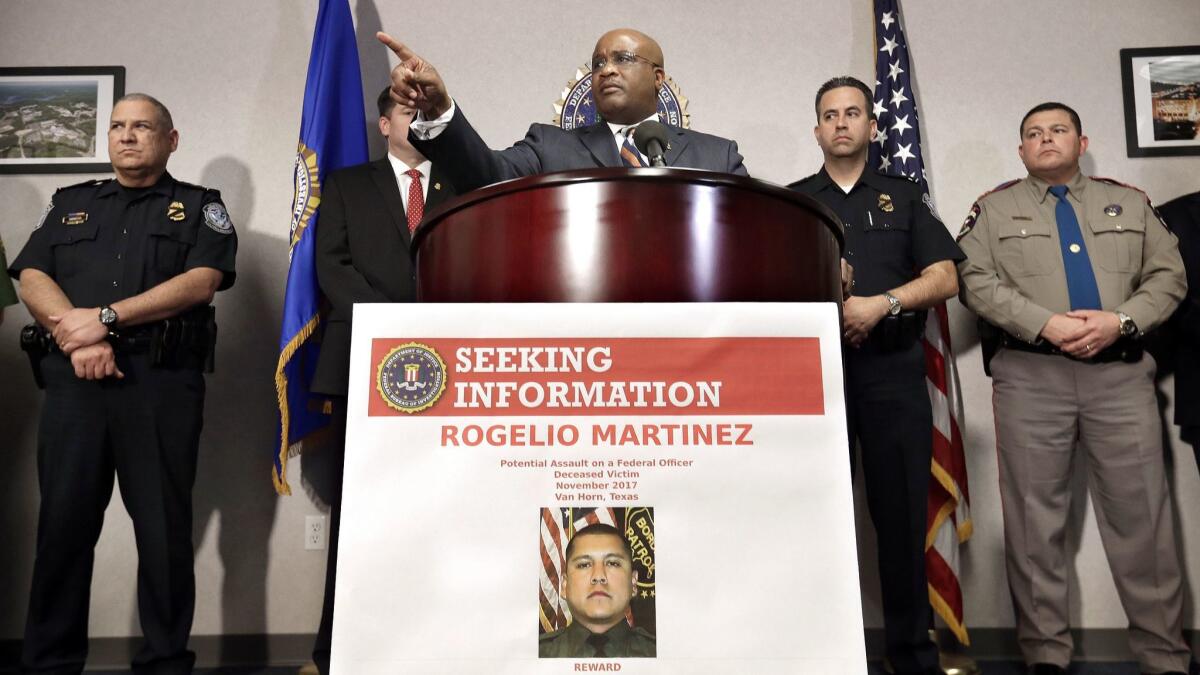

To this day, no one can tell Ochoa what happened to the man she was to marry. Agents in the Border Patrol union say he was assaulted by rock-hurling migrants. President Trump and other officials held up his death as example of the dangers faced by the Border Patrol and as another reason to build a wall on the U.S.-Mexico line. But this week the FBI said it had found no evidence of an attack; it offered no further explanation for Martinez’s death.

So for now, Ochoa continues to await answers. She said this week that on the last night of his life, Nov. 18, Martinez sent her a text message at 10:30 p.m.

“He was letting me know he was going to be out and about — that they were sending him out,” Ochoa said.

Martinez, a four-year veteran raised on the border, didn’t talk much about the danger of his work. So his fiancee took the late-night patrol in stride.

“OK,” she texted back. “Have fun.”

Martinez, 36, was working along Interstate 10 about 120 miles east of their home in El Paso. He had just radioed the nearest Border Patrol station to say he was checking a sensor that had been activated in a concrete culvert frequented by migrants and drug smugglers. He would be “sign cutting” — searching with his flashlight for footprints and other signs of activity on a moonless night in the high desert.

Fellow Agent Stephen Garland, at a gas station a dozen miles away in the nearest town, Van Horn, was summoned to assist Martinez.

Soon after, Garland, 38, called his wife on his cellphone, disoriented. She alerted the station in Van Horn that he and Martinez were in trouble.

Garland then spoke with a dispatcher, saying he wasn’t sure where he was but that the two were hurt and had run into a culvert.

The agents were found in the 9-foot-deep culvert. Both were still wearing their utility belts. Martinez still had his flashlight in his hand.

An autopsy released this week found Martinez died of “blunt-force trauma,” but how he received his injuries remains unclear. His manner of death was ruled “undetermined.” U.S. Customs and Border Protection Commissioner Kevin McAleenan sent a memo to agents late Wednesday that revealed more.

“The absence of evidence is a key factor in this case — not due to lack of effort or determination, but because evidence which would indicate the presence of other persons or the commission of a criminal act is not present,” the memo said.

McAleenan wrote that the FBI had found no evidence the agents were attacked, and noted further evidence indicating an assault by smugglers was unlikely.

“There were no defensive wounds on Agent Martinez or his partner who suffered injuries in this incident, and there was no third-party blood or DNA evidence recovered from the scene or from the agents’ clothing,” the memo said.

No footprints were found at the scene except those of the agents and first responders, and experienced trackers found no other sign of outsiders there, the memo said.

The memo said Agent Garland, 38, “fell” about 22 feet from Martinez, “landing on his back and sustaining significant injuries to his back and skull.”

“His resultant injuries have impaired the agent’s ability to recall the events of the incident,” the memo said.

Brandon Judd, president of the union that represents agents, the National Border Patrol Council, took issue with the memo and insisted the agents were attacked.

“In that area drug smugglers use booties to disguise their footprints,” he said. “The problem right now is there is no evidence of an attack, a vehicle accident, or a fall. And I would argue that where Agents Martinez and Garland’s bodies were a fall is just not likely.”

He said there was no evidence that a vehicle had approached the agents and knocked them into a culvert, and they had no injuries to their lower bodies from falling.

“I have an agent out at the scene right now. Agent Garland was [lying] approximately 13 feet from the culvert tunnels. It would be impossible to fall off the top 13 feet away. Part of Agent Martinez’s body was in the tunnel and part was out. Also not indicative of a fall,” Judd said Thursday. “Nothing makes sense except for an attack from behind. Especially when you consider they were specifically checking an area known for drug smuggling.”

Ochoa said she and Martinez’s family had met with FBI investigators in recent weeks, but learned nothing new.

“They haven’t given us any hope that they’ve found any new leads. It just seems like they’re getting nowhere,” said Ochoa, a medical assistant.

She didn’t know Garland or his family before the incident and hasn’t spoken with them.

“He hasn’t reached out to any of us,” she said.

She and Martinez had dated on and off for more than eight years. She watched him cast about for work after he studied graphic design at the University of Texas at El Paso. They lost touch when he joined the Border Patrol and moved across the state to work in Falfurrias, but reconnected when he returned home in 2016. By then, he wanted to settle down with his 11-year-old son, Sergio, in his hometown.

Sometimes he would tell her about the problems agents faced, including lousy radio reception. That was especially concerning to agents where he was patrolling the night he died — one of the most remote areas of the border where agents always work alone. Now Ochoa wonders why they didn’t have better radios, and whether that played a role in her fiance’s death.

“How can you not provide them that instead of spending all this money on a wall? What good is that when your agents are stuck out there?” she said.

Martinez wasn’t close with agents in Van Horn, and never talked about Garland, Ochoa said. She wants investigators to push the agent for more information.

Garland is still doing physical therapy and has not been cleared to return to work. He declined interviews through local Border Patrol union officials. An FBI spokeswoman said Garland was assisting with the investigation, but union officials said he still couldn’t remember what happened the night he and his partner were injured. The last thing he remembers that night was leaving home to start his shift, according to investigative reports.

“I really think that Agent Garland knows a lot more than what he says. I don’t believe that he doesn’t remember anything ... there was nobody out there but them two,” Ochoa said. “The fact that they’re not getting answers is because they’re not interviewing the right person.”

Ochoa, recalling her fiance’s attitude toward his work, said he tried to do his job humanely. He would tell her about agents mistreating migrants, and how it bothered him. He tried to reach out to migrants caught crossing the border illegally, especially to Central American and Mexican youths, whose numbers had increased in the months before his death.

“He had a big heart. He really enjoyed spending time with the kids they would catch … kids that lived the hard life outside of this country. He enjoyed getting to know them,” she said.

Ochoa’s fiance used to leave love notes tucked in her lunch, her gym bag or under her windshield. The day he died, after she returned from seeing him at the hospital, she found one last note waiting, hidden in her makeup bag: “I love you.”

molly.hennessy-fiske@latimes.com

Twitter: @mollyhf

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.