Native Americans rewrote the playbook for preserving public land — and Trump is trying to erase it

- Share via

Near the summit of Comb Ridge, in a high-desert region of dancing shadow and red rock splendor, serrated peaks form one of southeast Utah’s most recognizable landmarks.

It is hallowed ground for the Navajo and other Native American tribes whose ancestors scaled cliffs to build stone settlements on ledges and alcoves beneath trackless mesas.

Eleven months ago, descendants of these ancient people notched one of the great political achievements in Native American history. Following 14 months of government-to-government negotiation between the United States and five Native American tribes, President Obama signed Proclamation 9558.

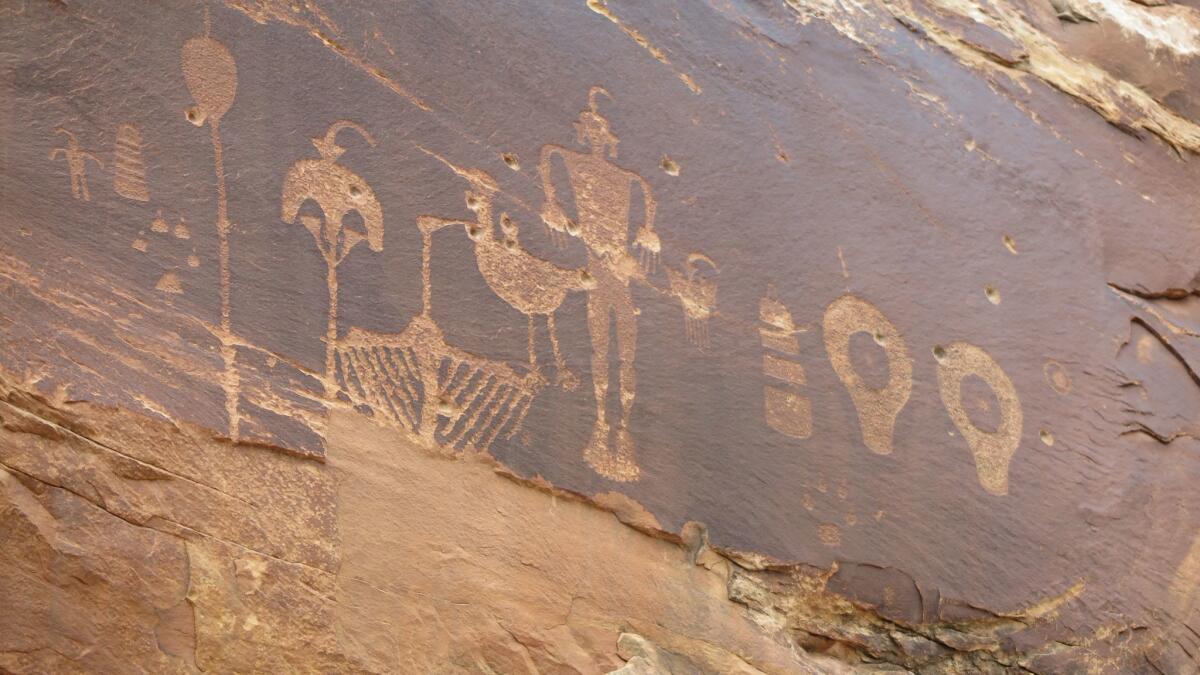

The proclamation, made under the presidential authority of the Antiquities Act to protect public lands, conserves over 100,000 Native American archaeological and cultural sites within the newly established 1.35-million-acre Bears Ears National Monument.

Much of the history of Native Americans in the centuries after European settlement is a ledger of lost land — getting pushed off lands they considered sacred. This time, they gained protection for their land in a way that had never happened before.

That achievement is now under siege by the Trump administration, also in an unprecedented way.

He may not have known it at the time, but when Obama signed Proclamation 9558, he set in motion a far-reaching confrontation over land, resources and political influence that could reshape rural communities and decide stewardship of the West’s public domain for the rest of the century.

Utah’s Republican congressional delegation immediately vowed to amend the Antiquities Act to strip its authority for presidents to act on their own to protect large expanses of federal land. A bill to do that, sponsored by Rep. Rob Bishop (R-Utah) and supported by the Trump administration, cleared the House Natural Resources Committee, which he chairs, five days after it was introduced in October. No hearing was held.

Its passage would mark a decided tilt in favor of industrial and political forces that have worked for decades in the West to dismantle safeguards for federal land and the environment. Its defeat would strengthen the influence of conservationists and tribes to develop and install new safeguards.

President Trump’s antipathy to the antiquities law and the new monument has galvanized Native American groups, who see the standoff as another test of their strength a year after the confrontation over the Dakota Access pipeline in North Dakota — another instance in which Trump reversed an Obama decision that favored a native tribe.

“We understood that it would provoke a reaction,” said Shaun Chapoose, a Ute Tribal Business Committee member, referring to the Bears Ears designation. He is a member of the Bears Ears Commission of Tribes that Obama established to help manage the monument.

Next month, Trump is expected to go to Utah to announce his formal decision to change the boundaries of Bears Ears and several other monuments, including the neighboring 1.9-million-acre Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument. The president has already informed Republican Sen. Orrin G. Hatch of Utah that he intends to shrink both.

To some extent, the differences between Obama and Trump in managing the public domain are familiar for the West. Recent Democratic presidents have tended to side with environmental and Native American advocates, Republicans with grazing, mining and energy interests that support greater development of public lands.

Other facets of the division, though, are new. Obama designated 29 new national monuments, more than any other president. And although previous presidents have adjusted boundaries, legal scholars say no president before Trump has considered such a sweeping declassification of national monuments nor attacked the premise of the antiquities law.

In April, the president signed an executive order that directed Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke to review boundary and management changes for 27 national monuments established under the Antiquities Act since 1996, most of them by Democratic presidents Obama and Clinton.

The Trump administration’s review fits with its other ambitions for the West’s public lands. The president and his aides have set out to reverse Obama-era restrictions on mining in the Grand Canyon, repeal rules for improving oil and gas leasing practices on public lands, and promote a program of “American energy dominance” that could open boundary regions of national parks and the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to oil and gas drilling.

The president’s public lands program has deep support in the regions of the rural West, like San Juan County, Utah, where grazing, mining, and oil and gas production still have economic relevance. It reflects long-standing frustration about federal management practices that are perceived as heavy-handed.

“The truth is, you’ve got a community of people who care about each other and care about the land and have protected it,” said Phil Lyman, a 53-year-old accountant and San Juan County commissioner whose opposition to federal land managers has gained national prominence. “All we want to do is be peaceful and have quiet enjoyment of our surroundings. This monument designation dramatically affects that.”

How? By encouraging thousands more people to visit a culturally and historically important preserve that is not prepared to handle them.

“The Antiquities Act is intended to preserve items of antiquity,” Lyman said. “You start using it as a massive landscape management tool and you’re going to lose it for what it was designed to do.” He argued that “industrialized recreation” at Bears Ears “stands to destroy the very thing the monument purports to preserve.”

Opposing the Trump administration is a nationwide counterforce of environmental lawyers, Democratic lawmakers, recreational and tourism business leaders and Native American tribes. These groups are united by several goals. One is to strengthen existing safeguards and develop a new, ecologically sensitive, energy-efficient economy. A second is to preserve sensitive lands that are sacred ground for Native Americans.

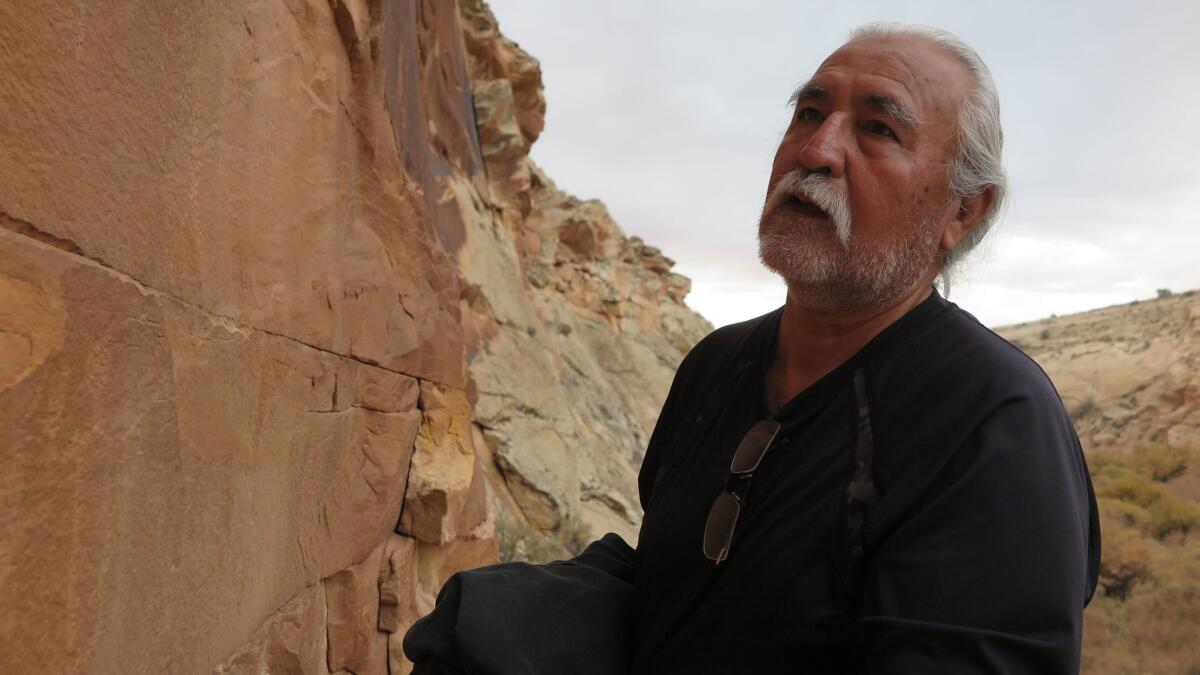

“These lands offer a form of healing that we want people to accept so we can live in harmony together,” said Willie Grayeyes, a Navajo leader and chairman of Utah Diné Bikéyah, a nonprofit policy group formed by Utah’s Navajo community leaders to advocate and organize support for the Bears Ears monument.

The outcome of this clash, the most intense since the Reagan administration, will determine whether the president’s goal to limit restrictions over the West’s land and natural resources is a sound strategy for economic development or a treacherous exploitation policy that has outlived its economic worth.

The town of Bluff, a scratch in the desert near the Arizona border with 258 residents, is the front line in the monument struggle. Established in 1880 by Mormon settlers, Bluff served briefly as a southern Utah outpost for a uranium boom that pocked the landscape with doghole mines after World War II to supply nuclear electricity generation and atomic weapons production.

San Juan County’s 17,000 residents are about evenly divided between whites and Navajo. Both groups see Bluff as a launch point for hikes and camping, Jeep excursions on rough dirt roads, and trips to forage for wood and herbs in one of the world’s most breathtaking landscapes.

“It’s massive. It’s stars in the night sky. It’s silence. It’s that kind of place,” said Jim Hook, the owner of Recapture Lodge, one of several comfortable hostelries in the town. “It’s so incredible. Your mind just goes crazy with the distance.”

Most Bluff residents long ago decided they were firmly on the side of the Native American tribes that wanted to preserve ruins and halt looting of artifacts from Bears Ears, and the environmentalists who wanted to preserve wildlands. Besides the lodges, the tiny settlement has several restaurants and shops that sell Native American art and crafts. Sales have increased with the monument designation.

Twenty-five miles north is Blanding, the biggest town in Utah’s largest county, and the epicenter of resistance to Bears Ears and federal land management agencies in southeast Utah. The country’s lone uranium ore processing plant still operates near Blanding, and the town’s business and political leaders, and many of its 4,000 residents — including Navajo and Ute families — resist what they see as insensitive and overly aggressive federal oversight of public lands.

But Blanding’s pro-development activism has not paid off economically. It has lagged behind other towns, such as Moab, 75 miles to the north, that have staked their claim on environmentally friendly tourism.

“We love visitors. Who wouldn’t?” said Lyman, the county commissioner. But he and the county’s two other commissioners join with Utah’s congressional delegation in asserting that establishing Bears Ears was an abuse of federal authority and the Antiquities Act.

“It’s not constitutional,” Lyman said. “Decisions have to be made at a local level. It’s like having kids. I will decide how to manage my child, not some other person.”

That view sharply diverges from the one held by the coalition of five tribes that negotiated the monument’s boundaries.

San Juan County’s western mesas and canyons, home to the distinctive rock formations known as Bears Ears, are where the Navajo believe their people rose from the earth.

For years, the leaders of the Navajo and four other tribes — Ute Mountain Ute, Ute Indian Tribe, Hopi and Zuni — spoke among themselves about protecting their home ground. But they feared that making those concerns public would invite government action to restrict access. It wasn’t until 2010, when they were invited by former Utah Sen. Bob Bennett to join a congressional public lands initiative, that the tribes got involved in a government process to decide how to use the land.

Ultimately, though, the tribal leaders said their ideas were consistently blocked or ignored. In 2015, convinced they couldn’t prevail, the tribes abandoned the congressional initiative and pursued a new course. Mindful that Obama and Sally Jewell, the Interior secretary, were sympathetic to their cause, and that Obama’s presidency was close to its end, the tribes focused on the Antiquities Act as a vehicle to secure Bears Ears.

In October 2015, the five tribes formally proposed setting aside 1.9 million acres in San Juan County and neighboring Grand County for the monument.

“This proposal is unique and wholly unprecedented,” said its authors.

Fourteen months later, Obama decided on a smaller monument and prepared a declaration that established a five-member tribal commission to work with federal agencies to draw up plans. The language of the proclamation, say historians, also put the tribes and the chief executive in closer spiritual alignment than any agreement ever signed by a U.S. president.

“Abundant rock art, ancient cliff dwellings, ceremonial sites, and countless other artifacts provide an extraordinary archaeological and cultural record that is important to us all,” said the proclamation, “but most notably the land is profoundly sacred to many Native American tribes.... The area's human history is as vibrant and diverse as the ruggedly beautiful landscape.”

While opponents in Blanding, Washington and Salt Lake City condemned the monument, tribal leaders celebrated. “We were finally heard,” said Nizhone Meza, the Utah Diné Bikéyah legal and policy director.

They also prepared for a new struggle to defend Bears Ears from a new administration. Mark Maryboy, a Navajo leader, and other activists say tribes and environmental groups are ready to unleash lawsuits in federal courts once Trump formally declares his decision.

“Let’s just say we have a lawsuit in the hopper right now,” Maryboy said.

Schneider is a special correspondent.

ALSO

Trump's environmental rollbacks hit California hard, despite Sacramento's resistance

Border Patrol losing agents faster than it can hire new ones

So what's behind the recent fraternity hazing incidents on college campuses nationwide?

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.