‘We are not leaving’: The final days of an Oregon occupier

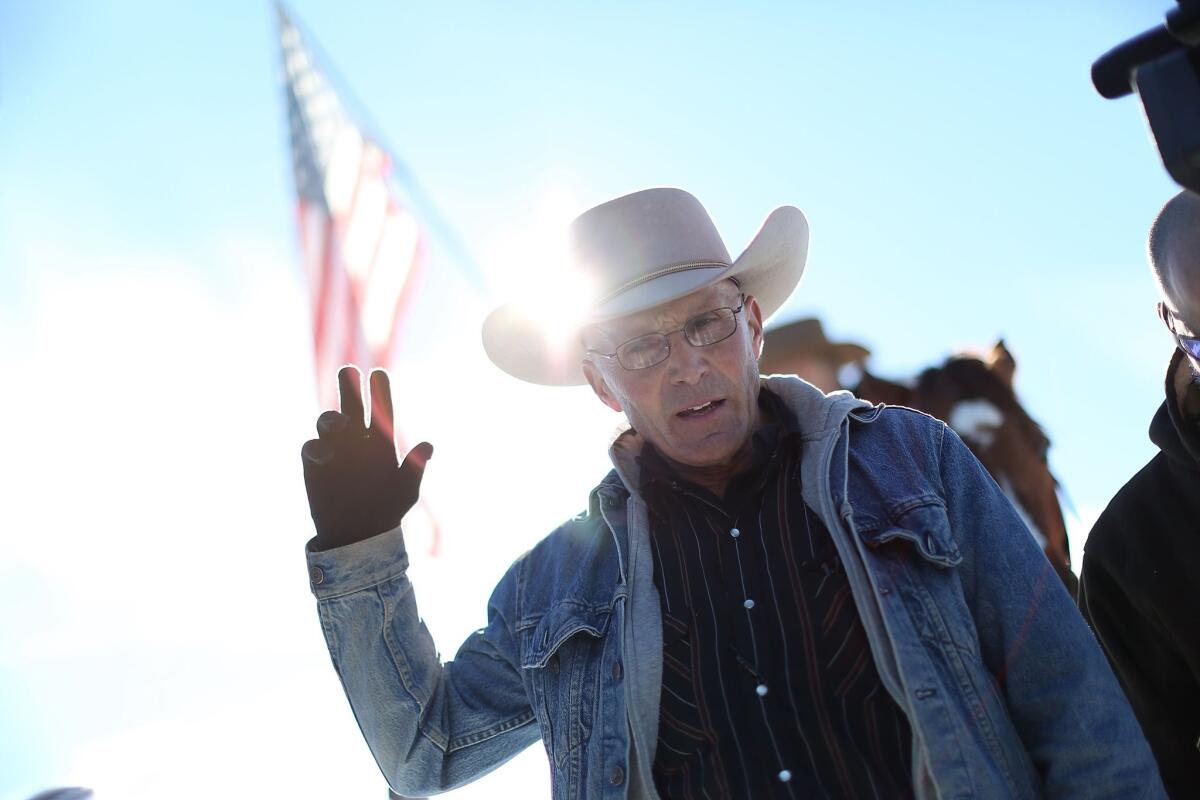

LaVoy Finicum speaks to the media as he and others occupied the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge on Jan. 15 near Burns, Ore.

- Share via

Reporting from Burns, Ore. — “Hello, America. This is LaVoy Finicum.”

Speaking into a camera, Finicum leaned against a stone wall, looking every bit the part of cowboy rebel he had become in the media, hands jammed into the pockets of his denim jacket, a holster on his hip.

It was Monday, the 24th day of the armed occupation of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge. It was also the last full day of his life.

Robert “LaVoy” Finicum was one of the occupiers protesting the federal government’s administration of public wild lands and the prosecution of two local ranchers. An Arizona rancher born and raised on Navajo land, Finicum in recent years had refashioned himself as a herald of a fallen America.

The FBI and Oregon State Police traffic stop and shooting of Robert “LaVoy” Finicum in Oregon on Tuesday. The video has been edited from the version released Thursday by the FBI.

In 2015, he wrote a novel called “Only by Blood and Suffering,” which warned of government collapse, and now he served as a spokesman for a small but well-armed protest movement.

“We see the saber-rattling of the federal government. We see the increase of their armaments. We see their intimidations,” Finicum told his YouTube viewers in a soft voice. “That’s not a cause for alarm on our part.”

In recent weeks, Finicum, 55, hinted often at his willingness to die, of how he’d prefer death over sitting in a jail cell where he couldn’t look up at the stars.

But overall, things had been relatively calm. Armed protesters were freely coming and going from the refuge. A troupe of singing children from Kansas had recently stopped by to give a small concert.

Finicum brushed aside the idea of surrender as others wondered when law enforcement — which had been trying to avoid a massacre like Waco or Ruby Ridge — would lose its patience and sweep in through the sagebrush.

“We are not leaving,” Finicum said. “We are here to do a job. Our course is fixed.”

::

As a two-vehicle convoy drove toward the town of John Day, an aircraft silently filmed from overhead.

Harney County had not been a happy place since the occupiers invaded the refuge on Jan. 2. Most, like Finicum, were from out of state, and they demanded nearly impossible concessions from the federal government. Residents bickered over whether to back the cause.

On Tuesday, protest leaders, including brothers Ammon and Ryan Bundy, decided to head to a community meeting in John Day in neighboring Grant County. They were on a campaign to measure and drum up support among locals.

But there’s only one convenient way to get to John Day from the refuge: U.S. Highway 395, a two-lane blacktop that winds into the forested Blue Mountains, where visibility drops dramatically, and where there’s no one around.

Which meant it was the perfect place to spring a trap.

A sign announces a closed road leading to the occupied federal wildlife refuge near Burns, Ore., on Jan. 29.

Mark McConnell was driving the second car in the convoy, a Jeep. He later said he had been chatting with another occupier, Brian Cavalier, when they saw nearly a dozen heavy-duty police vehicles waiting for them along the side of the road.

The FBI and the Oregon State Police’s moment had come, and their troopers and special agents sped into action.

They first pulled over McConnell’s Jeep, which also held Ammon Bundy, the most visible face of the occupation.

For all the public curiosity and concern over what Bundy might do, he and the other two men were detained without resisting. “They were a little rough on me, but I would be too,” McConnell said later, noting that he was armed.

But as law enforcement sped up behind the other vehicle filled with occupiers, a white truck, the driver took a little while longer to pull over.

Finicum was at the wheel.

::

Men in tactical gear trained their guns on Finicum’s truck, which came to a stop in the center of the highway.

One of the truck’s back doors opened, and Ryan Payne, an Army veteran from Montana, got out and surrendered.

But no one else followed, and Finicum’s truck sat idle, its brake lights blazing red.

In the foreword to his book, Finicum had thanked his family for the love and the memories they’d given him, then appended a warning: “It is my belief that freedom will arise again in this land, but only after much blood and suffering. This is my witness and my warning.”

Exactly 7 minutes and 7 seconds after he stopped his truck, Finicum took his foot off the brake and hit the gas pedal.

He chased the open road as it curved left, then right. The snowy mountain forest streamed past as the truck sped ahead.

But when the road curved left again, Finicum suddenly saw a police roadblock.

Finicum braked, veering off the road to the left — around a spike strip, officials said — and nearly hitting an FBI agent who had darted away from the roadblock. The truck came to a stop in a deep snowbank.

The soundless video taken from a surveillance aircraft shows Finicum springing out with his hands in the air seconds later.

“Just shoot me, then!” he called out, according to one of his passengers, Victoria Sharp.

When an Oregon State Police trooper came into view with his gun drawn — while another state trooper approached from behind — Finicum quickly lowered his arms and brought them toward his body. The FBI later said he appeared to be reaching for the loaded 9-millimeter handgun later found in his inside left jacket pocket.

The troopers shot Finicum where he stood, and he crumpled to the ground, stretching out his right arm after he fell on his back.

In the minutes that followed, officials tossed nonlethal noisemakers and irritants to incapacitate the passengers still in the truck: Sharp, Shawna Cox and Ammon Bundy’s brother, Ryan. Red gun-sight lasers danced over Finicum’s motionless body in the snow.

Ryan Bundy, who supporters later said suffered some kind of arm injury, was the next to emerge from the truck.

With his hands in the air and his cowboy hat still on his head, Bundy seemed to glance toward Finicum before walking toward police.

::

When the news broke, most of the remaining occupiers decided it was time to leave the wildlife refuge.

Men loaded their vehicle with supplies that had been sent in support of the occupation. Some did not take time to pack. Guns lay scattered around the compound, abandoned by their owners.

“Everybody panicked when they murdered LaVoy,” Sean Anderson, one of the final holdouts at the refuge, said later. “We had no communications, no walkie-talkies.”

Diesel trucks idled in the darkness. Children who had been in the camp were gone. The few holdouts scurried around the compound.

“Where’s all our Americans?” David Fry, a 27-year-old dental technician from Ohio, shouted in a video streamed live. “Where’s all our supporters? We didn’t get much!”

He panned his camera across a room of empty cots and turned to his viewers: “You guys are going to watch me die, live.”

“See you in heaven!” he told another occupier as if he were saying goodbye.

“Make sure you tell my daughter why I died,” another occupier said.

The end felt near.

“At least I got to meet LaVoy Finicum before he was murdered,” Fry told his viewers. “He was a good man.”

Pearce reported from Los Angeles and Yardley from Burns.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.