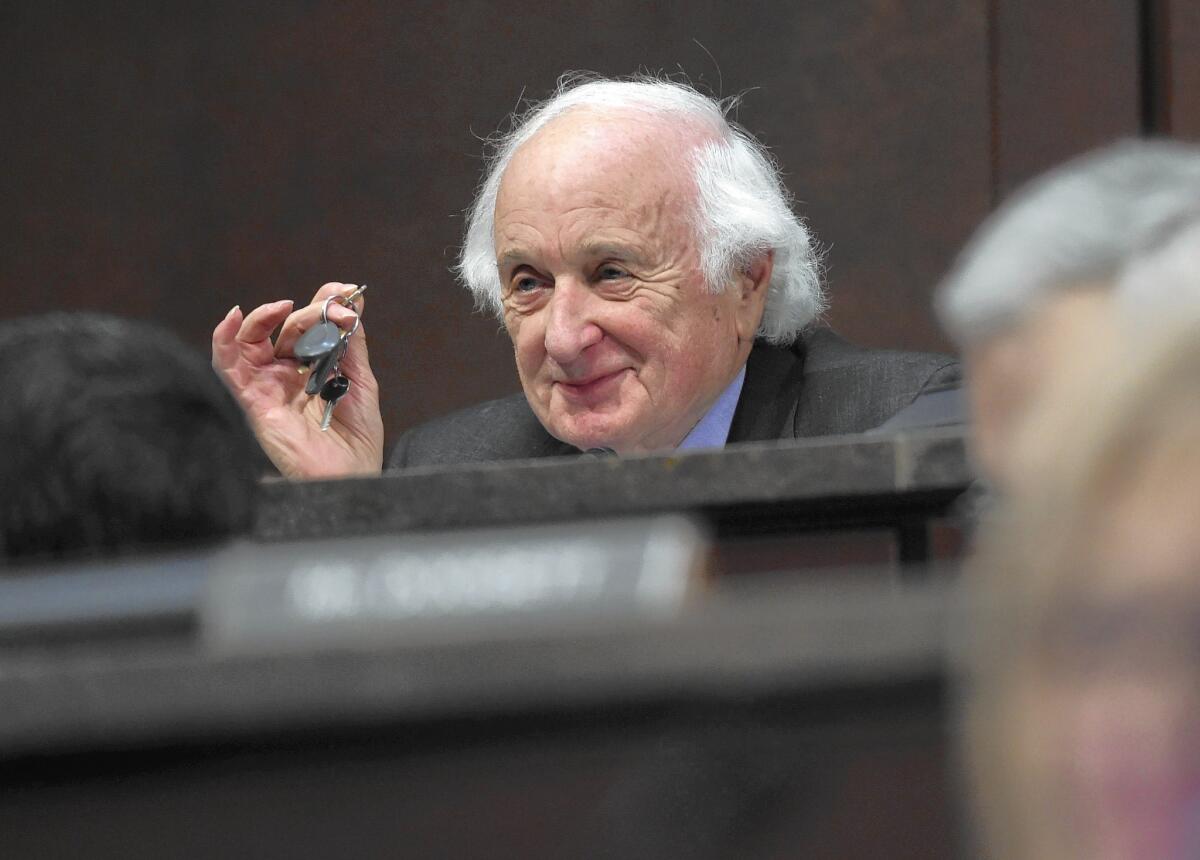

Rep. Sander Levin, 83, may pose greatest obstacle to sweeping Asia trade pact

- Share via

Reporting from WASHINGTON — Some years ago, the congressman from suburban Detroit bought an $11.46 universal joint from Joe’s Auto Parts, put it in his pocket and headed to Japan with a question: Why was it that foreign autos were jamming American streets, but the U.S. couldn’t export a simple coupling gadget to the Asian nation?

The answers were not reassuring to the young lawmaker, Rep. Sander M. Levin, who was just beginning to understand the scope of the nation’s trade imbalances.

Those experiences from the 1990s and earlier shaped Levin into one of the Democratic Party’s leading architects of a U.S. trade policy that embraces globalization but also strives to protect American jobs.

Now, as President Obama scrambles to negotiate a sweeping trade pact with Asian nations as a capstone to his final years in the White House, the administration’s biggest obstacle might very well be the 83-year-old congressman from outside Motor City.

Levin is as liberal as Democrats get, a gray-haired grandfather who spent his youth road-tripping across the West in an old DeSoto (and sometimes a rented Chevy) with his younger brother, the former Sen. Carl Levin. In three decades in Congress, he’s championed Michigan’s working class.

In the House of Representatives, he sits physically — and ideologically — opposite the younger Rep. Paul D. Ryan (R-Wis.), who is chairman of the powerful Ways and Means Committee and a free-market enthusiast. Levin, the committee’s top Democrat, advocates a strong government role to ensure a level playing field with trade partners.

If the president wants to push the 12-nation Trans-Pacific Partnership, or TPP, through Congress this year, first he must win over Levin and other leading liberals, convincing them to ease their demands and give U.S. Trade Representative Michael Froman a freer hand.

So far, Levin and other Democratic lawmakers are not so inclined, though the pact — covering countries that make up 40% of the world’s gross domestic product — has drawn support from many Republicans.

For Levin, who is in his 17th term in Congress, this could be one of the last big legislative fights of his career.

His pursuit of a trade policy that ensures labor, environmental and medical rights for workers, at home and abroad, recalls a brand of liberalism that once defined the Democratic Party, and may be rising again with the ascent of a newer generation of liberal leaders such as Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.).

“The basic issue is not whether you need trade, but whether you need to shape its course,” Levin said during a recent interview in his office, where the universal joint he carried so many years ago has been immortalized on a plaque resting by a window overlooking the Capitol.

After nearly five years of TPP negotiations, the White House hopes it is near a deal with the other Pacific nations, but it wants Congress to help with the last mile by providing so-called fast-track authority — a mechanism that has been used in the past to strengthen the president’s negotiating hand.

It asks Congress to agree in advance that lawmakers won’t amend the terms of any deal reached, and instead only approve or reject it with a simple up-or-down vote.

Conservative Republicans are loath to give the president such expanded power, but liberals are also wary of the administration’s request. Whether the White House can assemble a majority for passage remains uncertain as the Republican chairman of the Senate Finance Committee moves toward a vote next month on the fast-track bill.

In the meantime, the administration is lobbying hard, not only for the TPP, but also for Levin’s support, which White House officials know will carry considerable sway among his colleagues.

“We’re moving forward with the most ambitious trade agenda in American history,” Froman recently told a national conference of county administrators, including those from Los Angeles. “These are exciting times because the finish line for TPP negotiations is in sight. And that means more good jobs and a stronger middle class here at home.”

Levin is not so sure. Like many Democrats, he feels burned by some previous trade deals, which promised new markets for American goods but often left empty factories and jobless workers.

One of his top concerns remains the issue of currency manipulation. He has been pushing the administration to include trade rules that would prevent Asian countries from altering their exchange rates to make their exports cheaper.

He also is fighting for stronger labor and environmental standards, building off the landmark May 10, 2007, accord that Democrats struck with President George W. Bush to enforce workplace rights abroad.

But progress on these fronts has been slow, despite trade representative Froman’s almost daily visits to Capitol Hill to build support.

At this point, the administration appears to have pinned its hopes on a fast-track bill being negotiated by Sen. Ron Wyden of Oregon, the Democrats’ top member of the Finance Committee. Fast-track authority is also supported by the committee chairman, Sen. Orrin G. Hatch (R-Utah), and Ryan in the House.

But the administration’s strategy looks in peril as talks between Wyden and the others have dragged on.

Levin instead has focused his energy on shaping the trade pact itself, removing himself from the fast-track debate but warning that granting such authority would weaken Congress’ leverage to influence the final deal.

His stance has confounded some TPP opponents who worry Levin has marginalized himself, allowing the administration to try to circumvent his influence. They would prefer he fight more directly against fast-track.

“Before we fast-track a package, we have to know what’s in it,” Levin said.

The lull in Congress has created an opening for fast-track opponents to ratchet up the pressure. Warren has amplified her concerns over certain provisions of the trade bill, and the powerful AFL-CIO has announced that labor would freeze all federal campaign contributions to conserve its financial resources for the coming legislative battle.

“I think we’re going to be able to put together a majority and stop it,” predicted Richard Trumka, president of the AFL-CIO, who said trade pacts were “like a vampire: They keep coming down the street.”

At the same time, the White House has intensified its own campaign with upbeat blog posts about the pact’s potential economic benefits and regional visits to lawmakers’ home states as it tries to lock up votes from reluctant Democrats — and especially Levin.

“There’s tremendous pressure on him by the White House to do what they want,” said Rep. Marcy Kaptur (D-Ohio), a Levin ally since 1985, when the two young lawmakers made their first visit to Japan.

It was on that trip that Levin got the idea to use the universal joint as a symbol of the nation’s emerging trade imbalance. Kaptur had lugged boxes of Toledo-made Champion spark plugs to Japan, which she stuffed in her purse and gave to Levin to carry in his suit pocket. They handed them out to Asian officials.

“My heart goes out to him,” Kaptur said. “He’s been struggling with this his entire career.”

After all the years of fighting, Levin’s voice can sometimes sound tired, a creaky drone that belies a surprising stamina.

He recently remarried after his wife of 50 years died. During a congressional break last month he flew to Colombia to check on the status of labor rights imposed in an earlier trade deal.

In Levin’s 32 years in Congress, he has voted in favor of 14 trade pacts and opposed four — defying then-President Clinton to vote against the North American Free Trade Agreement.

How he will vote this time remains unknown to the White House, and maybe even to him.

“It’s all about trying to shape a trade agreement so you understand the impact on people, their livelihoods,” Levin said.

When asked whether he has talked to Obama lately about it, the congressman grew quiet. An older generation of elected officials doesn’t always like to boast about its proximity to power the way up-and-comers do.

“Yes,” he said.

And?

After a silence, he hinted that he hasn’t given up on trying to influence the final deal: “We were discussing content.”

Twitter: @lisamascaro

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.