Robert E. Lee was not the George Washington of his time. But a lot ties them together

- Share via

“Is it George Washington next week?”

His suggestion to reporters that Washington and Lee were similar figures in history —and that if memorials to one had to go, so did memorials to the other — is not new.

To examine this argument, we turned to Barton Myers, an associate professor of history at … wait for it … Washington and Lee University, in Lexington, Va.

The school was founded in 1749 as Augusta Academy. It went through two name changes before 1796, when Washington endowed the school with $20,000 to help it survive and the trustees showed their appreciation by renaming it Washington Academy. It later became Washington College. Lee became president of the school in 1865. After his death in 1870, the trustees gave the school its current name.

Myers’ answers have been edited for length and clarity.

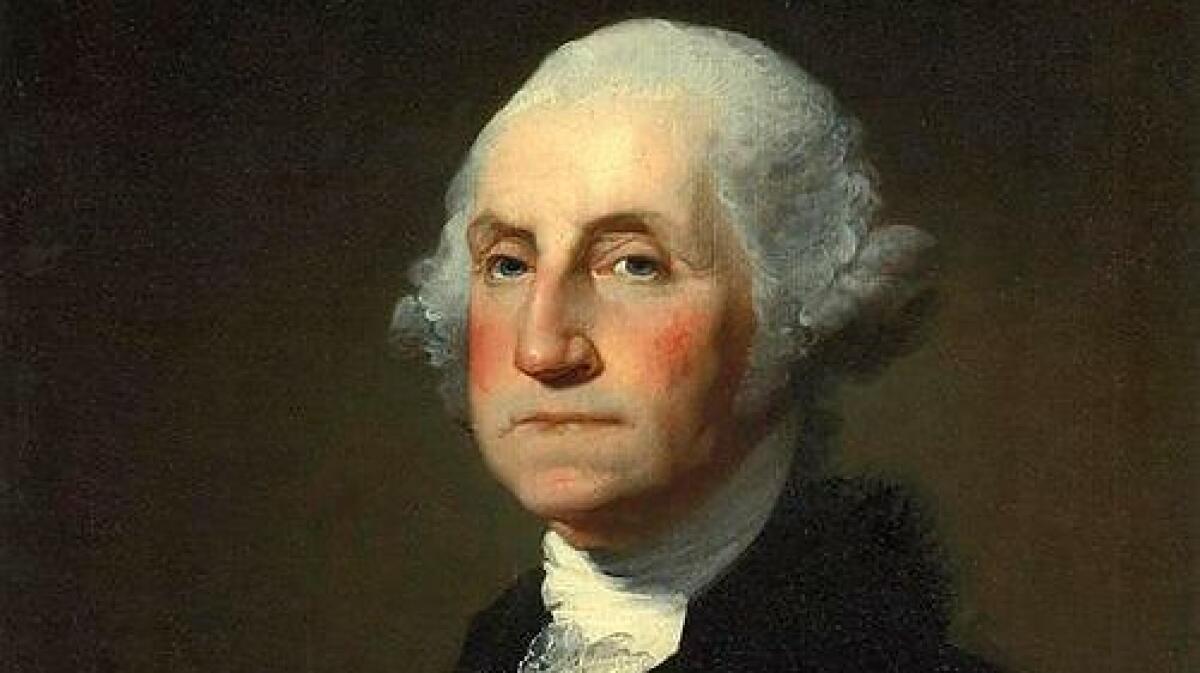

What are the similarities and differences between President George Washington and Gen. Robert E. Lee?

“I think there are strong similarities in terms of their backgrounds. They were both Virginians. Both men had served in the United States armed forces. Both men were recognized as great military figures and great battlefield commanders during their own time.

“These men both became figures of unity for their individual cause and symbols of their individual causes — men that the soldiers could rally around and see as symbols of their cause.

“There is also the family connection.”

What is that family connection?

“Lee ends up marrying into the Custis family [Martha Dandridge Custis, the widow of a wealthy Virginian named Daniel Parke Custis, married George Washington in 1759] and ultimately ends up administering the Arlington estate [the grounds of which were selected as the site of Arlington Cemetery]. He ends up inheriting even dueling pistols that belonged to George Washington.”

How were these men different?

“I think Lee really admired Washington as an example, as a military figure in particular, but ultimately departing from Washington’s example. Washington had actually worked during his presidency to put down a tax rebellion, the ‘Whiskey Rebellion,’ that occurred during 1791, during his administration. But Robert E. Lee joined the rebellion, ultimately choosing the state of Virginia after Virginia seceded from the Union.

“Both men did capable jobs.

“It took Washington a little bit of time to develop as a military commander at the level of general and army command, but ultimately he chose a ‘Fabian Strategy’ of battle avoidance that ultimately saved the American cause during the revolution, kept that army together as a symbol and ultimately was able to win that conflict.

“Lee, on the other hand, chose a very different path, a path of large-scale engagements that ultimately bled the Confederate Army, although winning many major victories along the way…. But subsequently finding defeat during the overland campaign and against Ulysses S. Grant, an equally gifted American commander.”

What were other differences between these two men in terms of the paths that they took?

“I think from Lee’s perspective he agonized over the decision to secede from the Union in 1861. Initially, he was offered command of all Union forces in the field by Gen. Winfield Scott, and he chose at first to ask Scott if he could sit the war out. And Winfield Scott, who is the greatest soldier in the republic at that point, said, ‘There is no room for equivocal men in my army.’

“And that was almost like a direct rebuke of Lee’s attempt to equivocate and be neutral. Lee ultimately went home, thought about it, and I think he knew the position of Virginia. Virginia, at that point, was headed out of the Union. Within days, Lee made the decision to resign his officer’s position, and within a few days after resigning subsequently was offered command of all Virginia state forces in the field, and ultimately Virginia joined the Confederacy.

“It was a very difficult decision for Lee, but he made a calculated loyalty decision, a loyalty decision that tiered Virginia and his family over the United States, an institution that he observed for decades as a dedicated, loyal U.S. Army officer. He made a decision to tier his loyalty to his family and to the state of Virginia over that.”

And what about Washington’s direction?

“Washington is a very interesting case. In some ways, Washington would be easily seen by the British government as committing treason early on — his part of instigating a rebellion and supporting that rebellion, though Virginia was a latecomer to the rebellion.

“But ultimately, Washington rises to be a central figure of unity in America. He was a figure of unity that brought together the colonies, Virginia being a leading one because of the command power and prestige. He was one of the wealthiest individuals in the country. He was a man of stature and respect because of his service during the French and Indian War and in the militia in Virginia during the [Revolutionary] War. And ultimately he became a unifying figure for all colonies to get behind.

“I think Lee has a similar purpose by 1864 for the Confederate armies.”

What about the argument that since both men owned slaves they were morally corrupt and should not be honored?

“Washington was certainly one of the largest slave owners in the country. A sum of his wealth came from ownership of slaves. He was also a huge landowner in the Ohio country and in Virginia was actively working to develop that throughout most of his life. When Washington dies, he takes the tact of freeing his slaves, directly in his will. Therein lies the partial separation.

“Washington, I think, saw the writing on the wall and saw the future of America, and in his farewell address as president worked very hard to tamp down ideas like sectionalism and division within America, and party politics.

“And he was in line with what was the Federalist Party at that point, which was a party of national institutions and supported things like road and bridge building. He was very much turning toward becoming a nationalist at a time when America’s colonies were very weak and needed unity.

“Lee administered the Arlington estate in the 1850s, was involved in punishing slaves. Some historical accounts, newspaper accounts that are reporting through hearsay, do account for Lee being involved in actually personally whipping a slave. They are not direct eyewitness accounts, but he was definitely involved in administering the day-to-day operations of a plantation. He clearly was involved in the recapture of slaves that had run away and the administration of the estate.

“I think Lee found slavery quite annoying as a day-to-day institution to run. His public comments on this are out there in a letter from 1856 to his wife where he talks about slavery being a great evil, but a great evil primarily to white people, because of what it was doing to the lower classes within the South and that it was a moral drag on those people.”

Is it reasonable in any way to say that Washington and Lee were equivalent figures in U.S. history?

“I think there was a time in the American South, especially immediately after the Civil War, when they were looking for heroes who were going to help bind up very open wounds. And as a result, people who participated in the veneration of Lee after his death, the ‘lost cause’ mythology and its erection, after the war, would have made that equivalent comparison.

“When the Confederacy was established in 1861, they put Washington on the Great Seal of the Confederacy. He was directly linked in symbolic fashion to what the Confederate cause was doing, by Confederates. I think there was an effort to make Lee an equivalent figure, by white Southerners in particular. After the war, people who had fought with Lee in his army wanted him to be that figure.

“So yes, there was a time in this country where there were a lot of people, millions of people perhaps, who felt that way.”

When and why were these statues erected in the first place?

“It really comes in three phases.

“Most of the monuments [went] up around the 50-year anniversary mark of the American Civil War, which corresponds to veterans’ organizations meetings and the Jim Crow period of American history. Many of those monuments are directly related to the ‘lost cause’ mythology and the effort to reestablish firm white supremacy, and even the rise of the second order of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s.

“Then there’s a second wave of monuments that come and spike during the civil rights movement, but also the centennial period, which was a very celebratory moment during John F. Kennedy’s administration, looking at the American Civil War and reunion as a celebratory moment in American history.

“And then there was a third wave of monuments that has come within the last 30 or 40 years, that are predominantly markers on battlefields designed to either honor veterans of the war that are Confederates or actually interpret the specific places of units on battlefields.”

Should statues of both men be taken down?

“There are many concentric circles to this discussion. In part because there are national battlefields that include Confederate monuments, there are national historical landmarks that include Confederate markers and monuments, there are national military parks that include Confederate monuments — all of which are actually interpreted and well-interpreted by federal historians and people who work in the National Park Service.

“And there’s been a long-standing, established set of policies and debates within the National Park Service establishing that set of guidelines on how to interpret these monuments. So at the federal sites, ultimately I would say NPS policy is directly what should hold.

“I think local municipalities are going to make these decisions as they see fit and as they have public discussions and forums about them and we’re seeing that.”

For more on global development news, see our Global Development Watch page, and follow me @AMSimmons1 on Twitter

ALSO

Tensions grow inside ACLU over defending free-speech rights for the far right

With Trump and Congress increasingly at odds, hopes for Republican legislative agenda fade

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.