At Ft. Hood sentencing, Army spouses describe anguish of waiting

- Share via

FT. HOOD, Texas — When Angela Rivera and other Army wives heard there had been a shooting at this central Texas Army post four years ago, they immediately called their husbands’ cellphones.

No one answered.

On Monday, as testimony began at the sentencing of the man convicted of murder in the Nov. 5, 2009, rampage, Rivera and other wives relived the uncertain hours of what many here call Five November.

The shooting left 13 dead and more than 30 others wounded. At the time, Rivera had no way of knowing whether her husband, Maj. L. Eduardo Caraveo, was among the casualties.

She watched the news at home in Woodbridge, Va., hoping for clues.

“They just kept repeating the same thing: 13 dead,” Rivera said on the stand, tears in her eyes as she faced the man responsible.

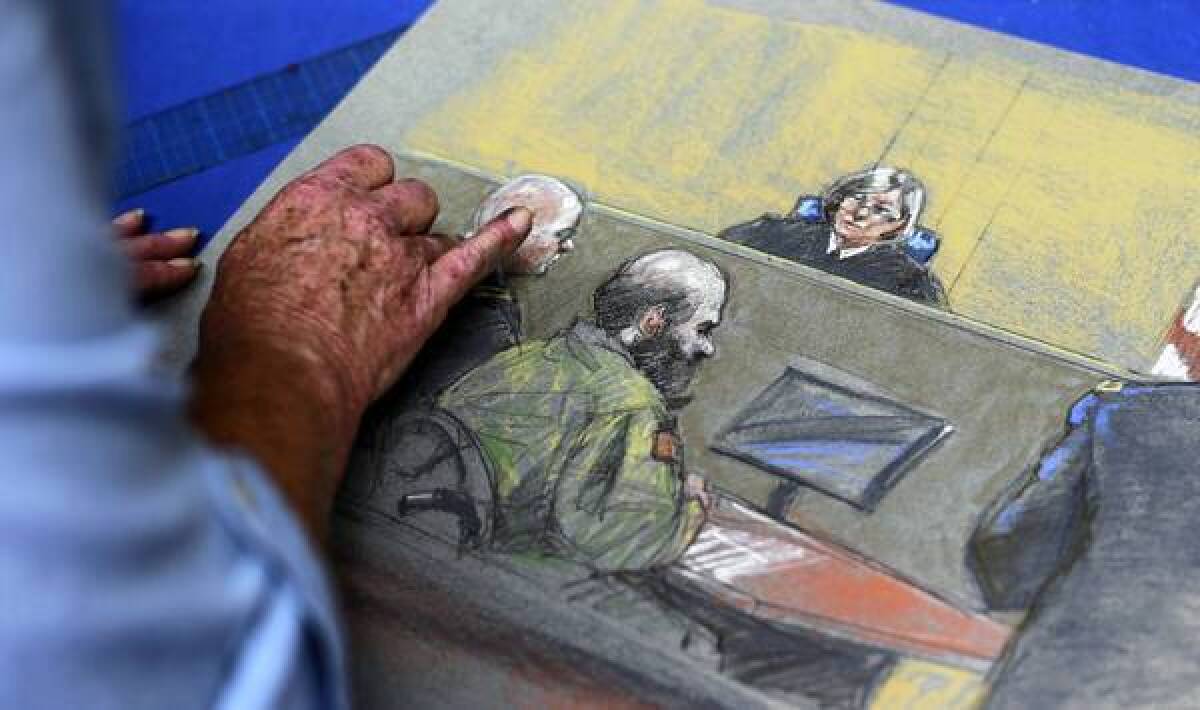

Maj. Nidal Malik Hasan stared back, impassive. The Army psychiatrist, who is defending himself, was convicted Friday on 13 counts of premeditated murder and 32 counts of attempted premeditated murder and could face a death sentence. The same military jury that convicted him will decide his sentence: 13 officers, all Hasan’s rank or higher.

Jurors scrutinized Hasan on Monday as his victims and their relatives testified.

Moments before the shooting, Shoua Her exchanged texts with her husband, Pfc. Kham Xiong, 23. She asked whether he was coming home for lunch, but he was busy. So she went outside to play with their three children.

A neighbor drove up with news of the shooting. She texted her husband again — no reply.

She called the Army hospital, her husband’s buddies, his first sergeant. No one knew where he was.

At 3 a.m., the doorbell rang. Through the window of her Army housing, she could see the pair of soldiers in uniform.

Gale Hunt was searching for news of her only son, Spc. Jason Hunt, 22, of Frederick, Okla., the boy with the crooked smile who had dreamed of joining the infantry and reenlisted while deployed in Iraq.

She left him a brief message: “When this is all over, just call.”

By evening, when he had not called back, she tried Ft. Hood, and reached a young man who kept telling her she needed to talk to someone else.

She was not surprised soon after to see the uniforms approaching her house.

“I kind of just turned my back on them and left them at the screen door,” Hunt said.

She picked up her cellphone, called her daughter, kept the line open and returned to the door.

“Go ahead,” she said.

As they spoke, Hunt said, “I could hear my daughter screaming.”

Caraveo, Rivera’s husband, had been at Ft. Hood preparing for his first deployment to Afghanistan. As news of the shooting spread, his wife back in Virginia kept checking for a missed call.

They never left messages. If they saw a missed call, they just called each other back.

She reached an official at Ft. Hood, who told her they had notified all the families of the dead. Still uneasy, Rivera tried to sleep.

At 5:25 a.m., the doorbell sounded.

She could see them through the glass in the door: two uniforms.

Rivera thought of her husband’s family — he was the youngest of seven. She thought of their youngest son, just 2 years old. Caraveo, 52, had been scheduled to fly home for Thanksgiving.

Instead, she received his camera and a few final photos. There was Caraveo in fatigues and helmet, hoisting a gun and smiling broadly under the mustache he cultivated. Prosecutors entered the photo into evidence Monday, along with photos of Hunt and other victims, displaying them on a small screen for the jury and Hasan.

Rivera told the jury that she has had to leave the home she shared with Caraveo. Too many reminders, she said: his car in the garage, his empty chair.

But she saved his cellphone. As long as she kept it activated and charged, she could call and hear him on voicemail, a legacy for their young son.

Then one day Rivera made a startling discovery. Caraveo’s voice had vanished. She called the cellphone company, but the voicemail greeting had changed. There was nothing she could do. Her husband was gone.

molly.hennessy-fiske@latimes.com

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.