California recall frenzy failed to materialize after Arnold elected

- Share via

It may be too soon, a mere decade after the California recall, to assess its lasting legacy. There have been significant changes in the way elections are run in the state, which, if proponents are correct, may eventually produce a more compromising class of lawmakers less beholden to special interests.

Far easier is noting all that wasn’t accomplished by the upheaval: The budget wasn’t balanced or the deficit painlessly whittled away. The interest groups and their seductive cash weren’t banished from Sacramento. As for easing partisan rancor, there have been precious few sightings of lions and lambs cuddling in the Capitol’s legislative chambers, or even on the lawn outside.

Something else didn’t happen: the cycle of dangerous, debilitating reprisal recalls — the ouster of Democrat Gray Davis leading to a retaliatory strike against Republicans, followed by an attack on Democrats, ad infinitum — that opponents forecast back in 2003.

The same warning was heard in Colorado during the recent recall effort aimed at two Democratic lawmakers targeted for their support of sweeping gun control legislation. It didn’t work there, either; both were tossed from office.

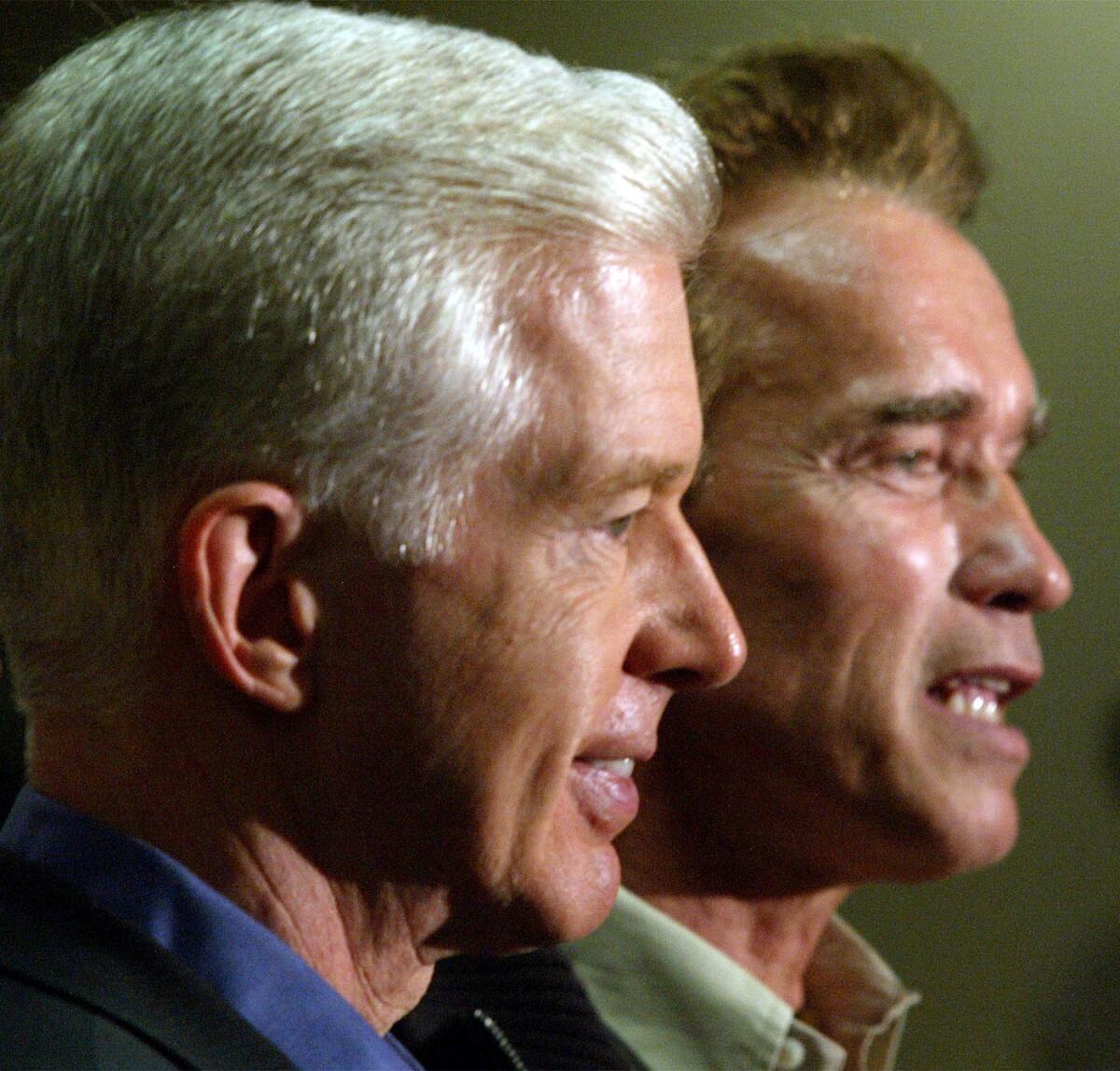

Although there were rumblings about yanking Davis’ successor, actor Arnold Schwarzenegger, from office, the post-recall recall movement went precisely nowhere. Indeed, in the last 10 years not a single state lawmaker has been ousted before their term expired, and it’s not for lack of contempt. During much of that time, the public approval rating for Sacramento lawmakers hovered below that of (insert object of contempt: toxic waste, smelly cheese, pond scum, political journalists).

So what happened? Or, more precisely, why didn’t recalls run amok?

Joshua Spivak, a senior fellow at the Hugh L. Carey Institute for Government Reform at New York’s Wagner College and an expert on recall elections, offers a simple explanation: Qualifying a recall is a lot of work that, judging from California’s experience, offers very little payoff.

“You can’t say that Gray Davis’ recall made that much of a difference on policy,” said Spivak, offering an analysis shared by many of the right, left and center. Nor, Spivak said, is that unusual.

“The recall has never met the fears of its opponents, or the hopes of its proponents,” he said.

Davis had the misfortune of becoming only the second sitting governor in the nation’s history to be recalled from office. The first, North Dakota’s Lynn Frazier, was ousted in 1921.

Spivak said there had been 38 state lawmakers recalled in the country’s history, 20 of them since Davis’ ouster. But before seizing on that figure as reflecting some sort of upward national trend, he noted that 13 of those took place in Wisconsin during a two-year period surrounding the fight between organized labor and Republican Gov. Scott Walker. Walker himself was the target of an unsuccessful recall effort in 2012.

It may be, as Davis suggested in a recent interview, that the recall is a sword that hangs over every politician in California. But if that’s the case, it’s a weapon that voters seem content to leave sheathed.

Twitter: @markzbarabak

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.