To some jurists, high court ruling brings vindication

- Share via

To judges and others who long battled strict federal sentencing rules for crack cocaine offenders -- considered draconian and racist by longtime opponents -- Monday’s Supreme Court decision brought vindication.

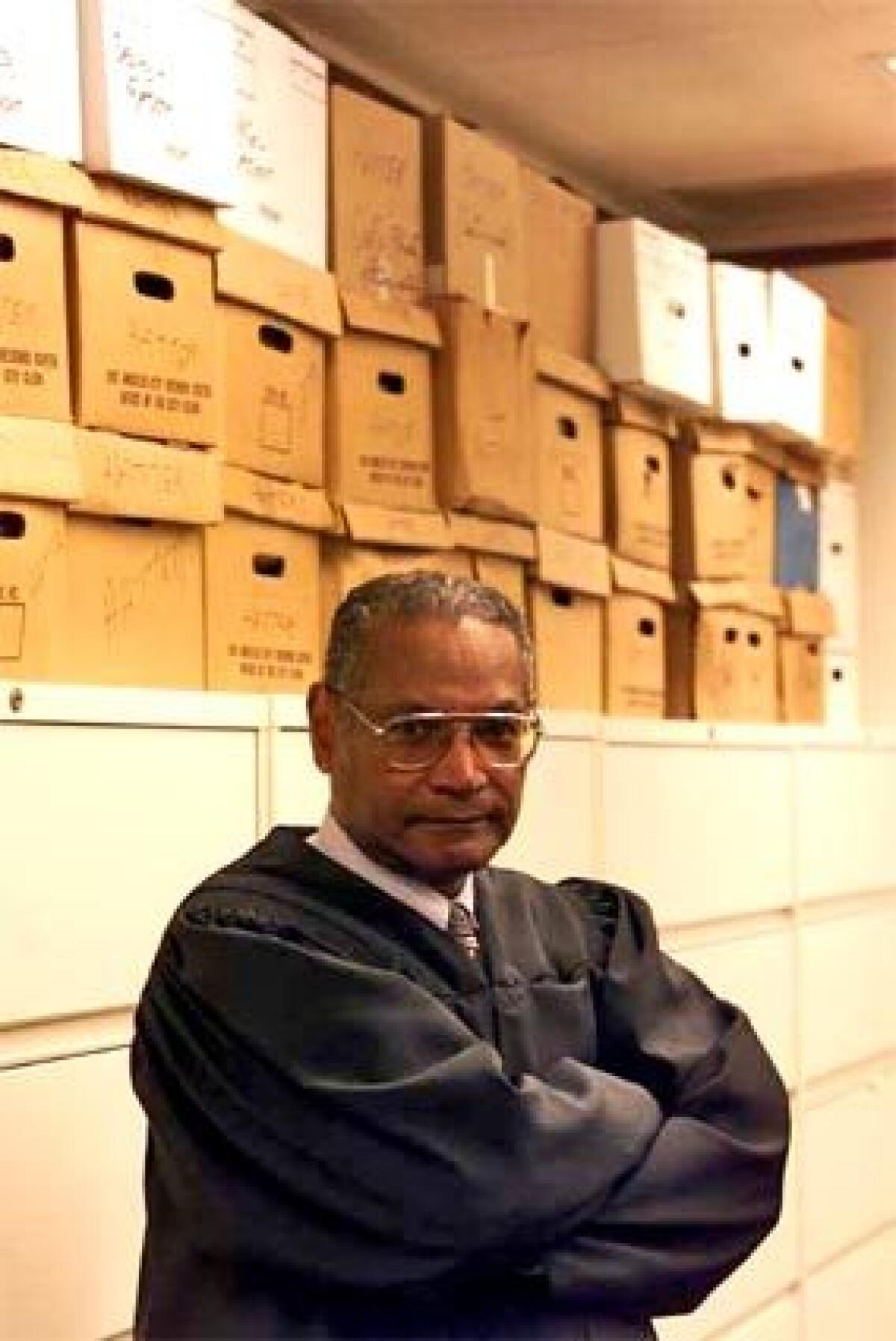

“I am delighted,” said veteran Los Angeles federal Judge Terry J. Hatter Jr., who for more than 20 years has publicly assailed federal sentencing laws as ill-conceived and unfairly targeted toward minorities.

“This brings some justice back to our justice system,” the 74-year-old jurist added.

The justices, in a pair of cases, held that judges can break from federal sentencing guidelines in drug cases, particularly those setting harsher terms for crack cocaine defendants than for powder cocaine offenders.

The severe crack guidelines particularly affected African Americans.

The guidelines for decades had drawn the ire of federal trial judges, prompting public protests and several resignations.

In congressional hearings, judicial conferences and network television appearances, Hatter, who was appointed by President Carter, had claimed that the federal sentencing guidelines were not really “guidelines,” but rather “mandates” that tied the hands of judges.

He also said the guidelines shifted power to the assistant U.S. attorneys who could virtually dictate sentencing by deciding how to charge defendants.

Hatter considered the issue so significant that he appeared on network television with federal Judge J. Lawrence Irving of San Diego, who stepped down from the bench over the guidelines, which he believed usurped the role of judges.

On resigning in 1990, Irving, an appointee of President Reagan, called the rules “absurd,” citing those requiring 10- to 20-year prison terms for so-called drug “mules” who transported narcotics in return for just a few hundred dollars.

“I can’t continue to give out sentences that I feel in some instances are unconscionable,” Irving said.

That same year, U.S. District Judge Raul Ramirez of Sacramento also cited the sentencing laws in his decision to leave the federal bench after 10 years.

A year before, another federal judge, Robert Sweet in New York, lamented in a hearing that he could not show mercy to a man convicted of selling nearly half a kilogram of crack.

“It is a mechanical task. I am a clerk,” Sweet said, before handing out a 20-year term.

More recently, U.S. District Judge Paul G. Cassell, in Salt Lake City, lamented that he had to sentence a first-time drug offender to 55 years, calling the term “unjust, cruel and irrational.” Cassell, a staunch conservative and former law clerk to Justice Antonin Scalia who now teaches at the University of Utah law school, unsuccessfully urged President George W. Bush to commute the sentence to no more than 18 years. Loyola Law School professor Laurie Levenson said Monday’s decisions clearly were a landmark and a vindication for the judges who spoke out.

“The pendulum has swung back. We had a 30-year experiment trying to tie the hands of judges. In the end, I think the Supreme Court realized that trusting trial judges might not be so bad; we get fairer sentences.”

Nonetheless, she cautioned that the two Supreme Court rulings did not change everything. “The guidelines are still a starting point,” said Levenson, a former federal prosecutor.

“There is a whole generation of judges who have been raised on the guidelines. So it may be a while before they feel their oats.

“They really have to be judges now,” utilizing their experience and knowledge of a particular case in a way they couldn’t before, Levenson added.

Ohio State University law professor Douglas Berman said he thought that Monday’s rulings were a rebuke to federal appeals courts that have overturned trial judges’ sentencing decisions.

He noted that other recent Supreme Court rulings have held that the guidelines are not mandatory.

That point was emphasized by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who wrote the majority decision in Kimbrough vs. U.S., which overturned a U.S. 4th Circuit Court of Appeals decision striking down a judge’s departure from the guidelines in a crack cocaine case.

“We hold that . . . the cocaine guidelines, like all other guidelines, are advisory only, and that the Court of Appeals erred in holding” that there had to be a significant disparity between sentences for crack dealers and powder cocaine dealers, Ginsburg said.

A federal trial judge “may determine” that in a particular case a sentence within the guidelines is “ ‘greater than necessary’ to serve the objectives of sentencing,” Ginsburg added.

That decision, as well as one permitting probation for a man who sold Ecstasy as a college student, indicate that the Supreme Court “has slowly but surely come to fully” understand the extreme severity of federal sentencing law, said Berman, who publishes an online blog, Sentencing Law and Policy.

The court’s decisions also were hailed by Mary Price, vice president and general counsel of Families Against Mandatory Minimums.

But she said the rulings did not address all of her concerns about severe federal sentences.

In addition to longer incarceration for crack offenders dictated by the sentencing guidelines, Congress approved anti-crack laws with strict mandatory minimum prison terms, which are not affected by Monday’s rulings.

The decision in the Kimbrough case “is a tremendous victory for those who believe that the crack sentencing structure is insupportable, as we do,” Price said.

The decision in the Ecstasy case, Gall vs. U.S., “is, if anything, even more important because it makes crystal clear that judges have the discretion to fashion sentences that are sufficient, but not greater than necessary to do justice in an individual case,” Price added.

Attorney John S. Gordon, who prosecuted many major drug cases as a federal prosecutor in Los Angeles in the 1980s and ‘90s, said that Congress had concrete reasons at the time to enact the crack differential.

“The common wisdom was that there were many more crack addicts than powder addicts,” Gordon said.

And there was “real world” evidence that “the crack business tends to be a more violent business than the powder business,” Gordon added.

But Ramirez and Irving, both of whom are now working as private judges, said they were pleased by the Supreme Court’s action.

“Judges should have the discretion to fashion sentences to fit the particular situation,” Irving said.

Ramirez was more outspoken: “I used to tell lay people I am the guy who watches the defendant at trial, sits up nights reading the pre-sentencing reports and is supposed to bring expertise to my decisions. Then, all of a sudden, a computer tells me how to do it. That’s not right.”

The pendulum has swung back in a ruling from a conservative Supreme Court, Ramirez said. “I feel vindicated.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.