Ruling puts release of inmates in California a step closer

- Share via

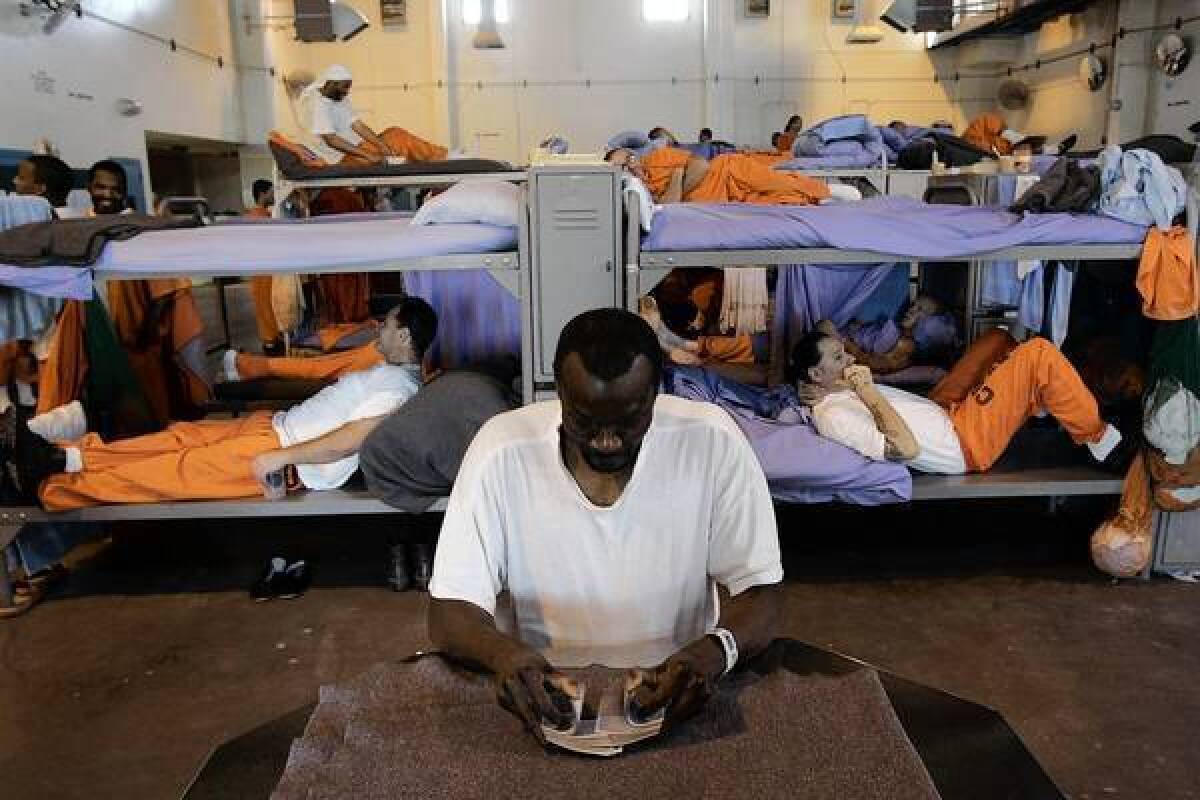

WASHINGTON — In a major setback for Gov. Jerry Brown, the U.S. Supreme Court on Friday declined to block a court order that he release 9,600 inmates from state prisons, moving California a step closer to relocating or freeing those prisoners by the end of the year.

The state can still pursue its appeal — and the administration vowed to do so. But the court’s 6-3 vote was a disappointment for Brown, who had launched a political crusade against a three-judge panel that has consistently ruled that overcrowded prison conditions violate the rights of inmates.

The panel has ordered Brown to bring the number of inmates in its prisons down to 112,164 by the end of the year.

Brown’s lawyers told the justices that the state has improved the treatment of inmates, easing crowding by keeping tens of thousands of prisoners in county custody and spending hundreds of millions of dollars to improve the quality of prison healthcare.

The panel’s demands, Brown has argued repeatedly, create a serious public safety threat. The state had asked the high court to put the panel’s order on hold while an appeal goes forward.

But the Supreme Court was not persuaded. The majority denied Brown’s request for a stay without comment.

Justice Antonin Scalia wrote a sharply worded dissent, which Justice Clarence Thomas joined. Justice Samuel Alito also dissented, but he did not join Scalia.

Scalia wrote that he does not believe the federal courts have the authority to order California to remove thousands of inmates from its prison system.

“California must now release upon the public nearly 10,000 inmates convicted of serious crimes — about 1,000 for every city larger than Santa Ana,” he wrote. The order, he wrote, goes “beyond the power of the courts.”

Scalia’s description overstated the situation. The state does not yet have to release prisoners, although that could happen by the end of the year. Federal judges have urged California to explore all options.

Although the latest turn in California’s long-running prison saga could lead to large-scale releases, the administration has alternatives.

It could, for example, send inmates to private facilities, most of which are out of state. The administration has contracts in place to enable such a move. But it would be costly to taxpayers and could create political problems with unionized prison guards.

Prison officials, meanwhile, have already started to identify thousands of inmates who are near the end of their terms. They are also looking at some 900 inmates who have serious illnesses and thus are considered less dangerous.

The governor’s office referred all questions to the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, which released a brief statement saying the state is not giving up on its legal fight.

“The state will pursue its appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court so that the merits of the case can be considered without delay,” it said.

But as the state’s prospects in court look increasingly grim, law enforcement officials are warning the rulings will have consequences.

“The federal courts are making decisions that can impact negatively public safety,” said Steve Whitmore, a spokesman for Los Angeles County Sheriff Lee Baca. He said the department is already stretched to its limit, and the county can’t handle more state inmates in its jails or convicted felons released early into the streets. “Enough is enough,” he said.

Kim Raney, president of the California Police Chiefs Assn., said the court had placed “convicted criminals’ concerns over the safety of California’s communities and citizens.”

The Supreme Court last weighed in on the prison dispute two years ago, when the court upheld by a vote of 5 to 4 a District Court three-judge panel’s order that the state ultimately bring its prison population down to 137.5% of the capacity for which the facilities were designed, or by 46,000 prisoners.

The high court agreed with the judges that prisoners were dying from a lack of decent medical care, resulting in “cruel and usual punishment.”

However, the Supreme Court left open the possibility that California could escape the court-ordered targets if it later showed that it was making progress in protecting inmate rights. With California still needing to remove 9,600 inmates to meet the court-mandated target, Brown returned to the Supreme Court seeking relief.

But inmate attorneys say the 6-3 ruling suggests that the high court is even less sympathetic to Brown now than it was two years ago.

“I think the governor has played this out now,” said Michael Bien, the lead lawyer in one of two federal lawsuits that triggered the release order.

As the state scrambles to deal with the court rulings, it is in the midst of a massive prisoner hunger strike, now in its fourth week. The prisoners are protesting the state’s practice of holding those accused of gang ties indefinitely in solitary confinement. Activists say overcrowding hampers alternative approaches, such as increasing rehabilitation programs.

“No good things can happen until the population comes down,” said Laura Magnani, an inmate advocate with the American Friends Service Committee in San Francisco. She was one of three advocates who met for an hour Friday with corrections chief Jeffrey Beard in an effort to negotiate an end to the hunger strike.

On Friday, 477 inmates at six prisons continued to refuse food. Prison officials said seven inmates required medical care, mostly in the form of fluids and electrolytes.

Some elected officials, meanwhile, used Friday’s decision to push the governor to modify his corrections agenda in other directions.

Los Angeles County Supervisor Michael D. Antonovich called on the governor to more aggressively move inmates into private facilities.

“The governor has only two choices,” he said in a statement, “transfer inmates to in-state and out-of-state detention facilities through contracting, or release 9,000 dangerous felons into our communities. It’s a no-brainer. The governor needs to stop pussyfooting.”

Halper reported from Washington, St. John from Sacramento.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.