Chris Hartmire, religious leader who helped establish United Farm Workers, dies at 90

- Share via

It was 1965 and throngs of Filipinos and Mexican workers walked out from their jobs in the grape fields of Delano, Calif., protesting unfair wages and unjust treatment and demanding the right to unionize. The strike sparked a yearslong battle that would ripple throughout the state.

Growers tried to crush all organizing efforts, zeroing in on the United Farm Workers and its charismatic leader, Cesar Chavez, whom they tried to paint as a communist. Workers were at first reluctant to follow Chavez’s call to action, afraid of what the repercussions could bring.

The fight even spilled into church pews, where workers and growers prayed together but clergy largely stayed silent.

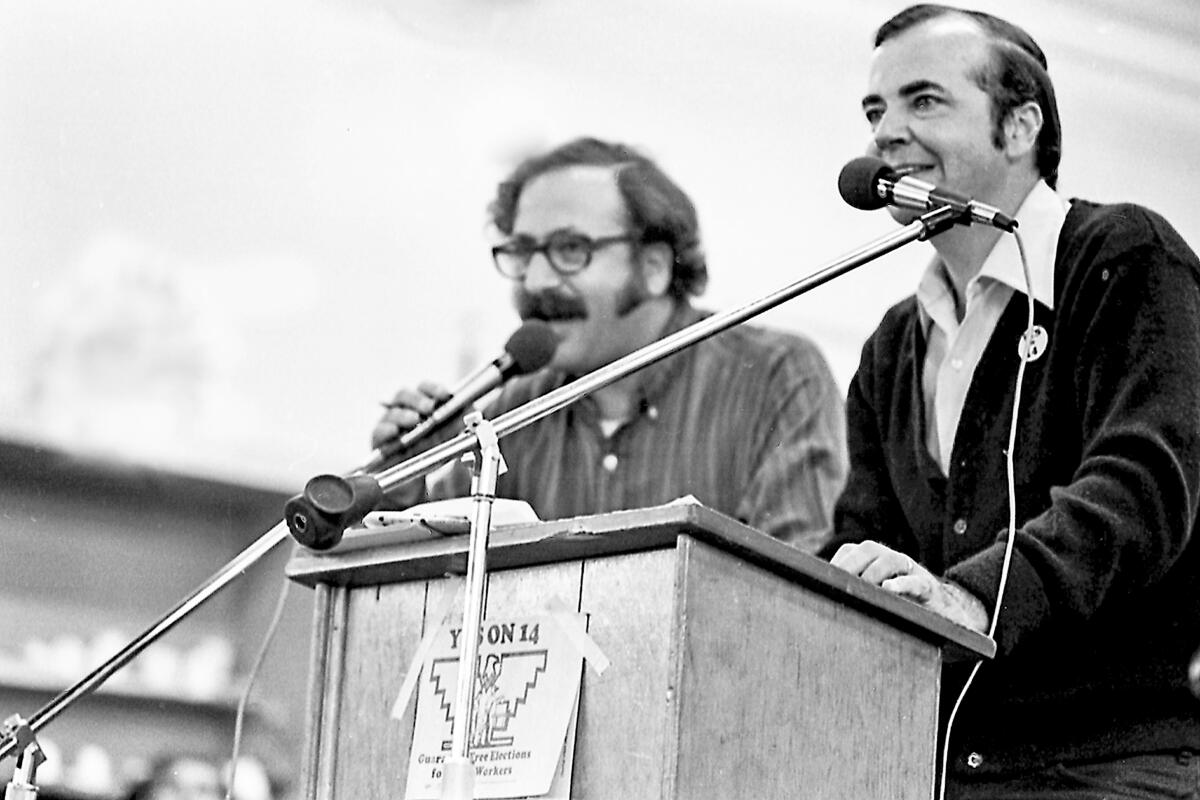

Into this chasm stepped the Rev. Wayne “Chris” Hartmire Jr.

He was the director of the California Migrant Ministry, a longstanding program that assisted farmworkers. They were among the first religious organizations to publicly back what would become the UFW, arguing its work was the epitome of Jesus’ call to help those who needed it. Hartmire invited clergyman across the country to witness the Delano strike firsthand.

“Believe me, you being here it’s just a whole lot more powerful than you realize,” Hartmire recalled in an interview telling anyone who took up his invitation.”Your presence here is more supportive of the work that the church actually deserves. Somehow, Jesus comes through, regardless of where our institutions are, and workers feel like, ‘This is a good thing we’re doing.’”

Whether in the Central Valley fields, Sacramento’s homeless scene or his retirement community, Hartmire rallied behind people to fight for basic human rights and preserve their dignity.

“They were the starting point in getting church people from all over the country involved with us. They were the instrument for interpreting us to people,” Chavez said of Hartmire’s involvement with the California Migrant Ministry in an 1977 interview with Sojourners Magazine. “Chris and his gang went up and down the country interpreting what we were doing in the light of the controversy that existed. And it split church committees wide open. People were taking sides. We didn’t win all of them, but we won a lot.”

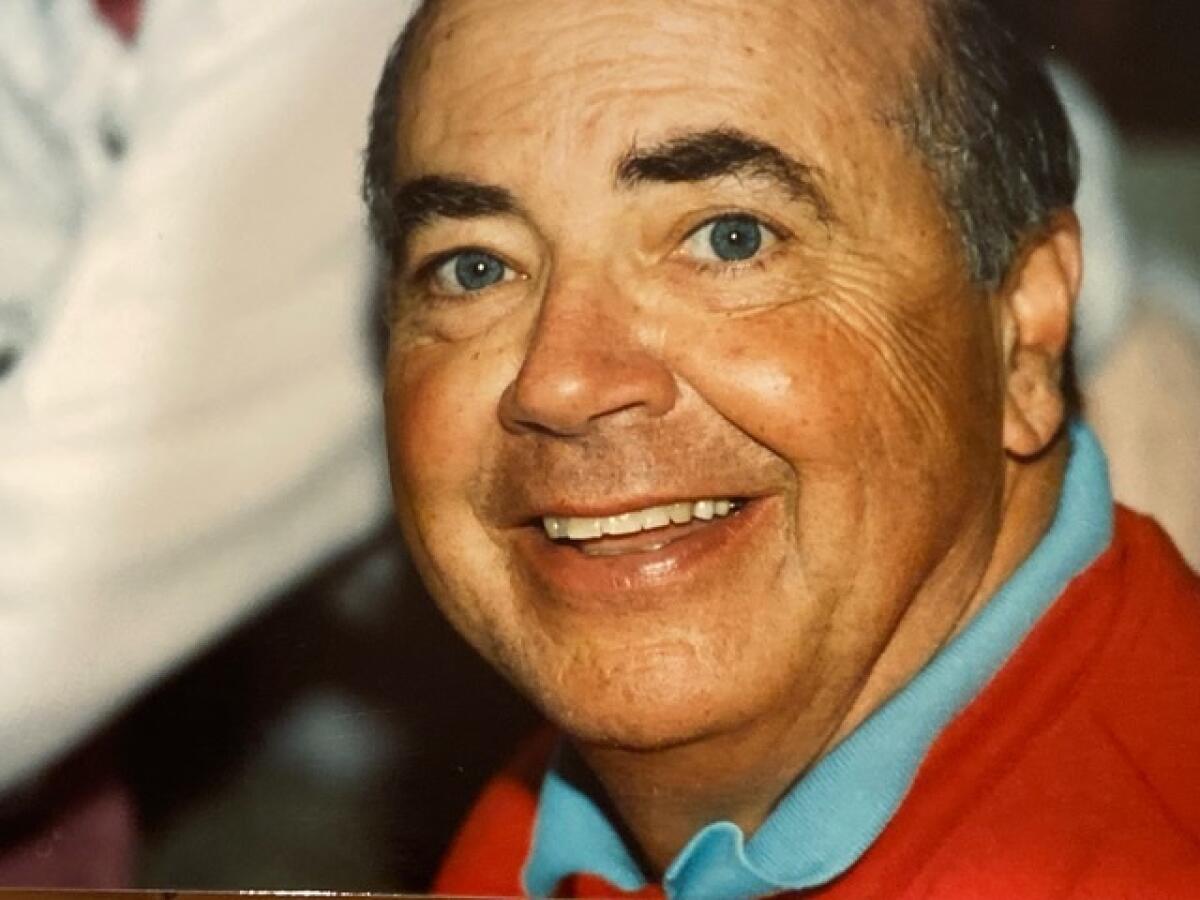

Even after splitting with the famed union at a time when he felt it had lost its way, Hartmire remained dedicated to a life of service. He died Sunday of congestive heart failure in Claremont, said his son, John. He was 90.

“If you were involved in unions or in the church community, you knew who he was,” John said. “If you didn’t, you certainly knew who Cesar Chavez was. But if you dug in and got to know more intricate details, [Hartmire] pops up everywhere.”

Hartmire was on a different trajectory before becoming a key leader in the farmworkers movement. He earned his bachelor’s degree in civil engineering from Princeton University, and later served in the Philadelphia Naval shipyard in the mid-1950s. The work came naturally but he longed for something more fulfilling.

He enrolled in Union Theological Seminary in New York City where writings by the German theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer —who denounced Hitler’s Nazi regime — galvanized his passion for social justice. After receiving his Master of Divinity and becoming an ordained Presbyterian minister, he worked with youth at the East Harlem Presbyterian Church. The experience convinced Hartmire to focus his work on helping the oppressed.

“A servant gets into the lives of the people, washes their feet, and serves them,” Hartmire would go on to say, according to a UFW tribute honoring his life. “A servant joins with farmworkers to be of service to them rather than bringing them services such as food or toys.”

Hartmire also joined the Freedom Rides to challenge segregated interstate buses — his first of many run-ins with the law in the name of social justice. By 1961, he had moved to Southern California with his wife, Jane “Pudge” and their three children after he was recruited to oversee the California Migrant Ministry, a charity-oriented organization that offered vacation bible schools, food giveaways and health clinics.

In 1966, as the Delano strike was underway, Hartmire told the Los Angeles Times the ministry had long helped farmworkers with resources but had failed to “attack root causes” of their suffering. “We must exist because churches in general have excluded the poor,” he said. “It reflects a sickness in the church.”

Internal firestorms brewed within religious organizations over the ministry’s role in the strike. Longtime friends lauded Hartmire’s ability to weave his community into social justice causes without coming across as holier-than-thou. Under his tenure, the National Farm Worker Ministry, which is still active today, was founded in 1971.

Rev. Gene Boutilier, a founding board member of the National Farm Worker Ministry, described his longtime friend as a “modern Christian revolutionary.”

“Good organizers do a lot of listening and help people recognize the strength within themselves,” Boutilier said. “Instead of saying, ‘I’m strong and I’m going to help you be strong,’ a good organizer enables what was already there and people being assisted with it.”

Hartmire ended his relationship with the UFW in 1987 when Chavez turned on him when he questioned the labor leader, much like he had with other early union members over the years. Despite being fully dedicated to “la causa,” Hartmire reluctantly left but continued the selfless work with a new endeavor.

LeRoy Chatfield, a Chavez confidante who first met Hartmire when the Delano grape strike began, recruited Hartmire to join his Sacramento-based nonprofit Loaves and Fishes. He joined the board and helped organized a nonviolent fast and sit-in outside the offices of Sacramento County supervisors in 2002 to pressure officials to open a year-round shelter for homeless women and children. The action was anticipated to last a year, but supervisors caved within five months, Chatfield said.

“He lived a life in service to the poor. He loved it, he did it and he was good at it. People loved him and yet, there’s not much public credit. I’m not saying there should be, but it’s just the way it is,” Chatfield said.

“The most important thing I think we provide is that we welcome people and we accept everybody,” Hartmire told CNN in 1994, “no matter who they are, no matter how they look or how they smell.”

Hartmire viewed his time with Loaves and Fishes as the most fulfilling work of his life, according to his son and Chatfield, because it allowed him to develop bonds and understand complicated dynamics often surrounding the homeless community. He officially retired from the nonprofit in 2002.

Even in retirement, Hartmire and his wife helped the lowest paid employees within the senior community demand compensation “well above” minimum wage, said Boutilier, who also lived in Pilgrim Place in Claremont.

Hartmire passed on his love of baseball to his family. An avid Dodgers fan, he would take his four children to see Dodgers greats such as Dusty Baker and Steve Garvey. They claimed their usual front row seats in left field. Once Baker autographed a baseball and handed it to Hartmire, thanking the family for the gum they’d given him, John recalled.

John remembers hearing his father chirping from the bleachers when the umpire made a questionable call during his high school games. Hartmire would often ask for his son’s thought process behind a play, never offering unsolicited advice but wanting to understand the reasoning.

“He didn’t get in the way,” John said. “He was there to support in the bad moments — losing a big game or striking out — and he was there to celebrate in the high moments.”

Hartmire is survived by his four children, nine grandchildren and two great grandchildren. A celebration of life, which will be open to the public, is scheduled for Jan. 28 at 3 p.m. at Pilgrim Place. Hartmire’s wife died in 2017.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.