Abortion clinics, not battle zones

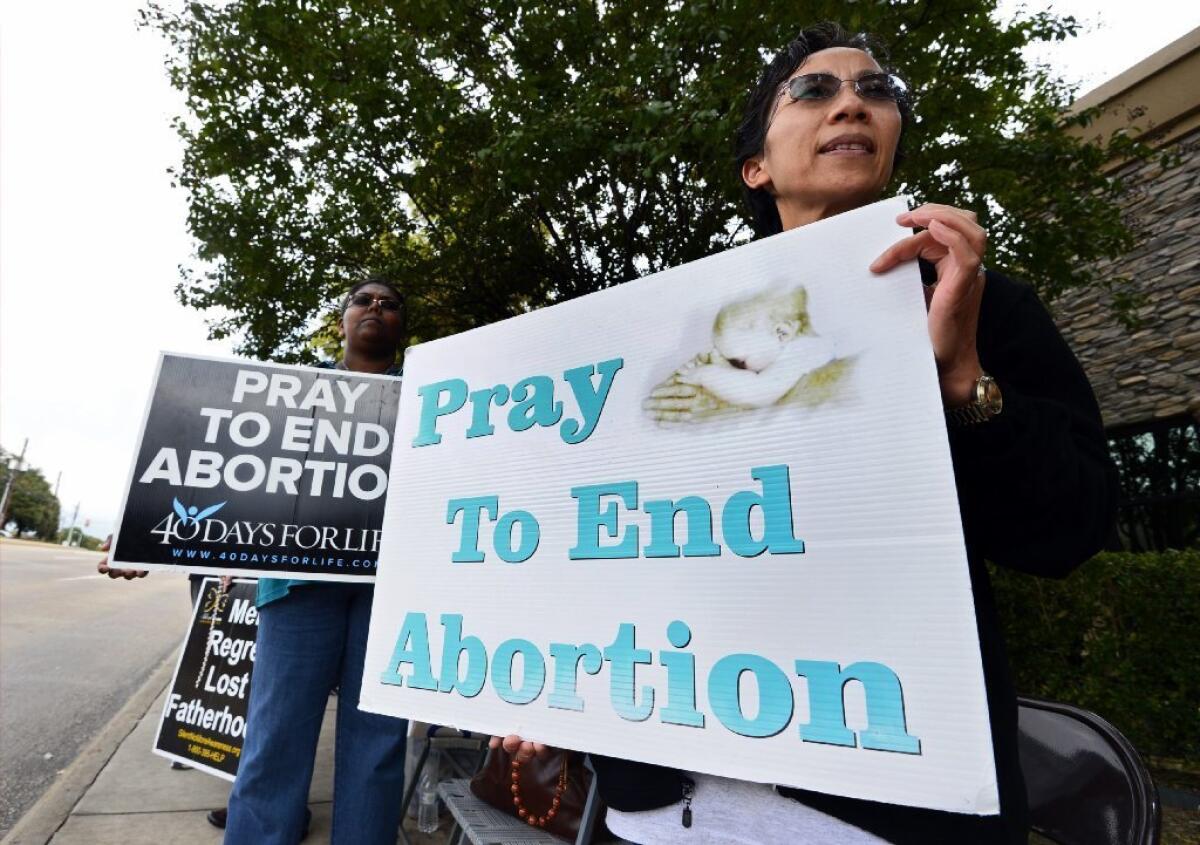

Protesters demonstrate near the Dallas abortion provider Southwestern Women’s Surgery Center. Pro-life activists have asked the U.S. Supreme Court to review the constitutionality of a Massachusetts law requiring protesters to stay at least 35 feet away from abortion clinics.

- Share via

A Massachusetts law that says “no person” may enter or remain in the 35-foot buffer zones established outside abortion clinics in the state has set off a controversial legal battle about the proper balance between the rights of speakers and the rights of those who must listen to them. Although several federal courts have upheld the law over the last few years, the Supreme Court has now agreed to review it. The high court should uphold it as well.

The petitioners, including a grandmother in her 70s who stands outside abortion clinics hoping to talk to women on their way in, claim that the law is an impermissible infringement on their right to express their opinion. They complain that they are held so far back from clinic entrances that they are prevented from communicating with the women in a conversational tone of voice, with eye contact, with offers of counseling. They are unable to hand out informational leaflets. Shouting from a distance, they say, is ineffective or counterproductive. When they do find a woman willing to have a conversation before she gets to the 35-foot zone, they are thwarted from continuing it once she moves into the zone.

The U.S. 1st Circuit Court of Appeals, which upheld the law in January, noted that the 1st Amendment doesn’t guarantee the right to an attentive audience “available at close range.” But it does require that, in seeking to protect audiences from “hindrance, harassment, intimidation or harm,” the state not place any more burden on the right of free speech than necessary.

YEAR IN REVIEW: Five disheartening moments for women in 2013 -- and one disappointment

No principle is more fundamental to a free society than the right to speak out in protest, but just because speech is vital does not mean that all other rights yield to it at all times. Indeed, time, place and manner restrictions are common.

In this case, the buffer zone is justifiable. Though there are many civil, reasonable antiabortion protesters in the world, history shows that some have turned the perimeters of reproductive health clinics into battlegrounds, using intimidation and sometimes violence. The fatal shooting of two clinic workers in Brookline, Mass., in 1994 by an opponent of abortion was the impetus for the law that is being challenged. It’s true that the law excludes all protesters, not just violent ones, from the buffer zone. But the state shouldn’t have to wait to see if a particular protester is going to harass people or turn violent.

The Guttmacher Institute, a research organization that supports reproductive health services and abortion rights, says that family planning clinics continue to report incidents of bombings, arson and vandalism, as well as violent protests and blockades. Fifteen states and the District of Columbia prohibit various acts directed at clinics and workers, including blocking entrances, threatening or intimidating staff and patients, making harassing phone calls to staff, damaging property or making excessive noise outside clinics. Along with Massachusetts, two other states have set up protective zones.

Besides, the 35-foot buffer zone doesn’t entirely prevent face-to-face conversations. A protester can’t walk and chat with a woman all the way to the clinic entrance, but a woman on her way to the clinic can pause outside the zone to have a conversation if she chooses. And even from 35 feet, the voices of protesters can be heard and their signs can be read.

The petitioners also argue that the law amounts to unconstitutional viewpoint discrimination because clinic employees are able to enter the buffer zone and talk to women. But healthcare workers assisting their clients aren’t engaging in advocacy; they’re doing their jobs. The court should reject this claim.

The 1st Amendment rights of protesters must be weighed against the ability of people to enter and exit health facilities without being intimidated and harassed by others determined to talk women out of having a legal procedure. In 1994, the Supreme Court held that “the 1st Amendment does not demand that patients at a medical facility undertake Herculean efforts to escape the cacophony of political protest.” The court should uphold the Massachusetts law, which targets speech only to the extent of attempting to ensure an environment in which women have access to safe, legal and effective medical services.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.