Op-Ed: ‘Saturday Night Massacre’: Key figures in Nixon’s 1973 Justice Department purge

- Share via

In 1973, President Nixon ordered the firing of special prosecutor Archibald Cox because he wouldn't obey Nixon's order to stop looking into Watergate. Two of the

It’s a phrase that came up again in January after

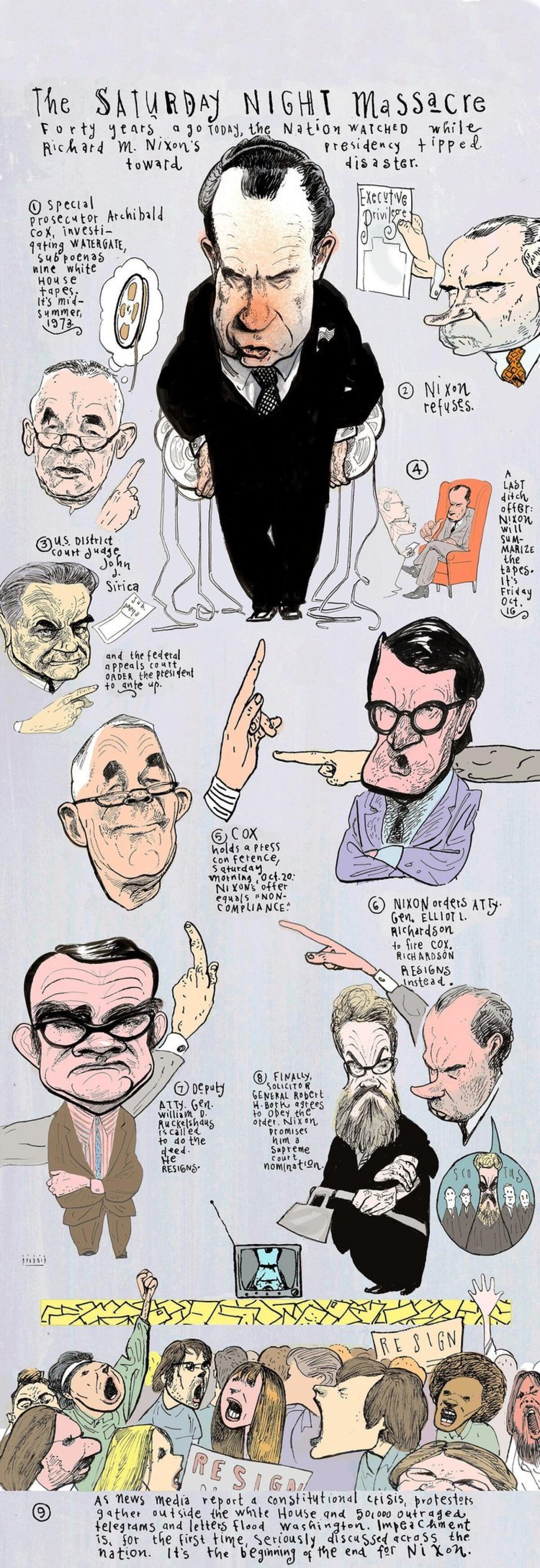

Three years ago, on the 40th anniversary of Nixon’s actions, artist Steve Brodner drew this guide to the key players.

Here’s more on the episode from deputy Op-Ed editor Susan Brenneman, originally published Oct. 18, 2013:

The “Saturday Night Massacre” was a scorched-earth moment in the Watergate affair.

On Oct. 20, 1973, the two highest-ranking members of the Justice Department, Atty. Gen. Elliot L. Richardson and his deputy, William D. Ruckelshaus, quit rather than follow President Nixon's order to fire Special Prosecutor Archibald Cox. Cox and the courts were pressing the president to release White House tape recordings that might shed light on whether he had a role in covering up a break-in at Democratic Party headquarters in Washington's Watergate office complex.

Nixon's move to block the special prosecutor was for most Americans their first up-close look at what the Watergate fuss, by then more than a year old, was all about: naked presidential power.

Nixon badly miscalculated on Oct. 20, 1973. When Richardson got the order to fire a defiant Cox, the attorney general instead went in person to the White House to quit his job. Ruckelshaus, next up at the Justice Department, was handed his orders by phone, and he too refused and resigned.

"You owe a duty of loyalty to the president that transcends most other duties," Ruckelshaus told a gathering of former U.S. attorneys in 2009. But "there are lines.... In this case, the line was bright and the decision was simple."

For

Here's where it gets interesting: Ruckelshaus was relieved that Bork did what did. He emphatically didn't want to see Cox fired, and he had refused "an order from his commander in chief" (that's the way Alexander Haig, Nixon's messenger, put it). But that wasn't the only thing on Ruckelshaus' mind:

"The solicitor general was third in command at the Department of Justice," he said, "and there the chain of command stopped. It's not clear what would have happened if Bork had refused.... Both Elliott and I had urged Bork to comply if his conscience would permit. We were frankly worried about the stability of the government."

By the time Nixon resigned, effective Aug. 9, 1974, and put an end to the "long national nightmare" of Watergate, it was clear that government stability (apart from Nixon's own hold on power) hadn't been the first concern of the president and his cronies.

With Watergate, the United States survived "a massive break of trust," Ruckelshaus said in 2009. "The center and the Constitution held. We also suffered greatly.... In my opinion, Richard Nixon's conduct ... did his country incalculable harm, and ... we have not yet fully recovered from some of the damage."

Updated May 9, 4:15 p.m.: This op-ed was updated with Trump’s firing of Comey.

This piece was originally republished on Jan. 30, 2017.

MORE FROM STEVE BRODNER:

Imagining the royal court of Donald the First

Readers react: Did a caricature of Donald Trump go too far? Depends on your opinion of the president

The home stretch: Highlights — more or less — of the last days of campaign 2016

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.