Op-Ed: Why it’s way too soon to give up on the Arab Spring

- Share via

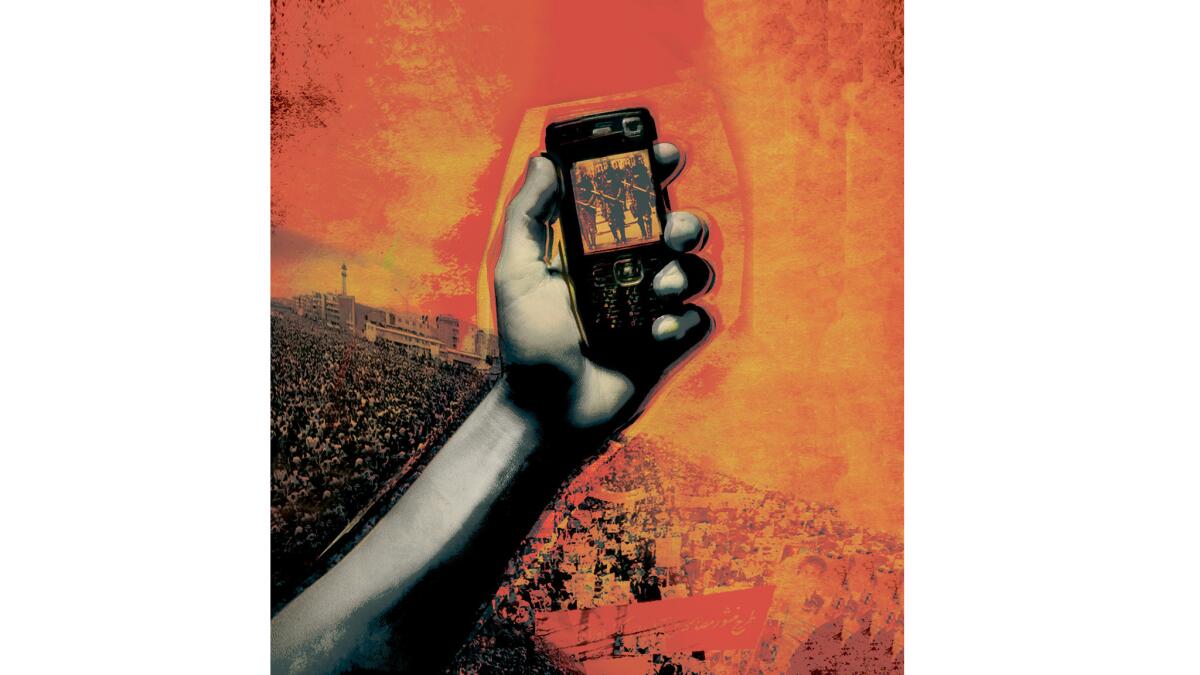

Three and a half years ago, the world was riveted by massive crowds of youths mobilizing in Cairo’s Tahrir Square to demand an end to Egypt’s dreary police state. We watched transfixed as a movement first ignited in Tunisia spread from one part of Egypt to another, and then from country to country across the region. Before it was over, four presidents-for-life had been toppled and the region’s remaining dictators were unsettled.

Some 42 months later, in most of the Middle East and North Africa, the bright hopes for more personal liberties and an end to political and economic stagnation championed by those young people have been dashed. Instead, some Arab countries have seen counterrevolutions, while others are engulfed in internecine conflicts and civil wars, creating Mad Max-like scenes of postapocalyptic horror.

But keep one thing in mind: The rebellions of the last three years were led by Arab millennials, by young people who have decades left to come into their own. Don’t count them out yet.

Given the short span of time since Tahrir Square, it is far too soon to predict where these massive movements will end. During the “Prague Spring” of 1968, let’s remember, a young dissident playwright, Vaclav Havel, took to the airwaves on Radio Free Czechoslovakia and made a name for himself as Soviet tanks approached. But then, after a Russian invasion crushed the uprising, Havel had to seek work in a brewery, forbidden to stage his plays.

That wasn’t the end of the story, however. Two decades later, after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, Havel became the first president of the Czech Republic.

Or consider the French Revolution: Three and a half years after the storming of the Bastille, the country was facing a pro-royalist uprising in the Vendee, south of the Loire Valley, a conflict that ultimately left more than 100,000 (and possibly as many as 450,000) people dead.

And let’s remember that a decade passed between the Boston Tea Party and the American victory in the Revolutionary War.

There are, of course, plenty of reasons for pessimism in the short- and perhaps even medium-term in the Middle East. But when it comes to youth revolutions, it’s a pretty good bet that most of their truest accomplishments will come decades later. The young Arabs who made the recent revolutions are, in fact, distinctive: substantially more urban, literate, media-savvy and wired than their parents and grandparents. They are also somewhat less religiously observant, though still deeply polarized between nationalists and devotees of political Islam.

And keep in mind that the median age of the 370 million Arabs on this planet is only 24, about half that of graying Japan or Germany. While India and Indonesia also have big youth populations, Arab youth suffer disproportionately from the low rates of investment in their countries and staggeringly high unemployment rates. They are, that is, primed for action.

Analysts have tended to focus on the politics of the Arab youth revolutions and so have missed the more important, longer-term story of a generational shift in values, attitudes and mobilizing tactics. The youth movements were, in part, intended to provoke the holding of genuine, transparent elections, and yet the millennials were too young to stand for office when they happened. This ensured that actual politics would remain dominated by older Arab baby boomers, many of whom are far more interested in political Islam or praetorian authoritarianism.

The first wave of writing about the revolutions of 2011 discounted or ignored religion because the youth movements were predominantly secular and either liberal or leftist in approach. When those rebellions provoked elections in which Muslim fundamentalists did well, a second round of books lamented a supposed “Islamic Winter.”

Yet, in Egypt, the Muslim Brotherhood has been ousted (albeit through a reassertion of power by the military). In Libya, Muslim fundamentalist candidates could not get a majority in parliament in 2012. Even in Tunisia, where the religious right formed the first postrevolution government, it was able to rule only in coalition with secularists and leftists.

As they wait their time, many of the millennial activists who briefly turned the Arab world upside down and provoked so many changes are putting their energies into nongovernmental organizations, thousands of which have flowered, barely noticed. Others continue to coordinate with labor unions to promote the welfare of the working classes.

In this way, they are learning valuable organizational skills that — count on it — will one day be applied to politics. Their dislike of nepotism, narrow cliques and ethnic or sectarian rule has already had a lasting effect on the politics of the Arab world. And two or three decades from now, the twentysomethings of Tahrir Square and the Casbah in Tunis and Martyrs’ Square in Tripoli will, like the Havels of the Middle East, come to power as politicians.

We haven’t heard the last of the Middle East’s millennial generation.

Juan Cole is director of the Center for Middle Eastern and North African Studies at the University of Michigan and the author of “The New Arabs: How the Millennial Generation is Changing the Middle East.” A longer version of this piece appears on tomdispatch.com.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.