Opinion: Who really gets hit by the spike in Medicare premiums?

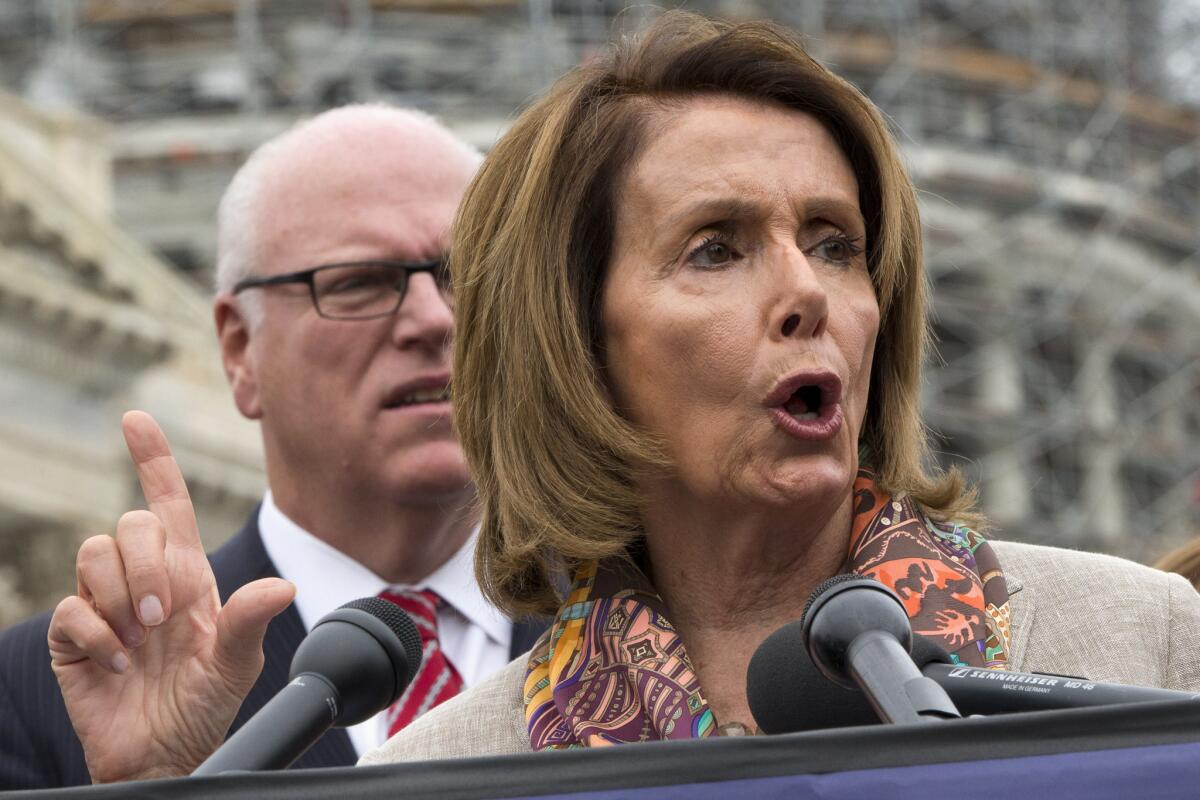

Rep. Joseph Crowley (D-N.Y.) listens as House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi (D-San Francisco) speaks during a news conference on Capitol Hill in Washington on Oct. 7 to discuss the looming increase in Medicare Part B premiums for some seniors.

- Share via

The federal government’s announcement that Social Security benefits will not receive a cost-of-living increase in 2016 — the third no-COLA year since the last recession ended — prompted the usual complaints from seniors and advocacy groups about the way inflation is measured and the inadequacy of benefits.

They have a point about the measuring methodology, which uses the consumer price index for urban wage-earners and clerical workers. That index, which actually showed a drop in total prices, isn’t a very realistic measurement for people who don’t commute but do spend a lot of money on prescription drugs.

But there’s one well-publicized aspect of the frozen benefits that isn’t as outrageous as it’s made out to be. This is the so-called Medicare Part B spike, which the New York Times gravely warns could cause “nearly one-third of Medicare beneficiaries [to] have record increases in their premiums unless Congress intervenes.”

It’s certainly true that millions of elderly people will face higher premiums for Part B, an optional but essential part of Medicare that covers doctors’ charges and outpatient care bills. But it’s just not true that nearly one-third of Medicare beneficiaries will face record increases in their premiums.

Under federal law, enrollees in Medicare Part B pay one-fourth of its costs, with federal taxpayers essentially covering the rest. But Part B premiums are based on the beneficiary’s income, so seniors of greater means pick up more of the tab than their less wealthy peers.

Here’s where Social Security COLAs come in. Under federal law, seniors earning less than $85,000 per year (or $170,000 per couple) who have their Part B premiums deducted from their Social Security checks — and most of them do — never see a reduction in their net benefits because of Part B. Any increase in premiums is limited to the amount of the annual COLA.

But that creates a squeeze-one-part-of-the-balloon situation. Premium income has to cover 25% of the cost of Part B. When the COLA is less than the increase in Part B costs — and it consistently has been, with annual Part B costs increasing 5.3% over the past five years while inflation has stayed below 2% — some other group of Medicare beneficiaries has to cover a larger share than the group that’s held harmless.

With roughly 70% of Medicare beneficiaries held harmless, that means the squeeze will be felt that much more strongly by the rest. For some in that group, premiums will be about 50% higher in 2016 than they were this year.

Before you turn purple with outrage, though, consider who’s in the category being squeezed.

The largest segment is nearly 11 million seniors and disabled Americans with incomes so low, they are also enrolled in Medicaid, the joint federal-state insurance program for the impoverished. Medicaid pays their Part B premiums, which means that federal taxpayers will have to fork over about $3 billion more, and state taxpayers about $2 billion. In California, the state’s tab could be more than $500 million.

Another segment is people who are newly signing up for Medicare. They’ve never paid Medicare premiums before, so they don’t face a “record increase.” In fact, if they’re coming into Medicare from a non-group insurance plan, they’re probably going to see their premiums drop significantly.

Granted, while these beneficiaries might not suffer from the kind of rate shock the New York Times alleged, they’re still not being treated fairly. That’s because they’ll pay higher premiums next year than most of those who entered Medicare in 2015 or before.

Another group hit by the higher premiums isn’t receiving Social Security checks, so it’s not as if they’re being struck by a “one-two punch” (as the New York paper put it) of higher premiums but flat Social Security benefits. This group has two sorts of members: about 1.6 million retired federal workers covered by a government pension, not Social Security, and seniors who’ve elected to defer the start of their Social Security checks. The latter have the same complaint as the new beneficiaries — they’ll be paying higher premiums than their peers simply because they’ve decided to hold off receiving the retirement benefits they’re entitled to.

If there are any Medicare beneficiaries who really could be described as having to deal with higher premiums when their Social Security benefits are being held flat, it’s the folks with incomes of $85,000 or more per year who aren’t eligible for fully subsidized Part B. That’s about 5% of all Medicare beneficiaries, or roughly 2.5 million people.

This group’s premiums are based on their incomes — the higher the income, the lower the federal premium subsidy — but all face the same increase of a little more than 50%. The new monthly premiums are projected to range from $223 for singles with adjusted gross incomes of $85,000 to $107,000, to $510 for those with incomes above $214,000.

That’s a steep increase, even if the rates are below the market price. But while these beneficiaries’ incomes may be fixed, they’re significantly better off than the average Medicare enrollee, the vast majority of whom won’t face higher premiums next year.

The obvious response to the spike — and the one that Democrats and their allies are pushing for in Congress — is to have the federal government pick up more of the increase in Medicare Part B costs. After all, that’s what the federal and state governments will do for the beneficiaries who are also enrolled in Medicaid. Before lawmakers do so, though, they should consider who it is that they would be rescuing, and why.

Follow Healey’s intermittent Twitter feed: @jcahealey

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.