How the FBI and the Los Angeles Times destroyed a young actress’ life 50 years ago

- Share via

Fifty years ago, a senior editor at the Los Angeles Times came into possession of a dangerous piece of gossip, leaked to the paper by the FBI. The Times printed it without fact-checking it, and the life of a famous young actress was destroyed.

The leak was malicious and the information was almost certainly wrong. It was intended by the FBI to damage the reputation of the actress, Jean Seberg, as punishment for what the bureau saw as her radical political beliefs. When Times gossip columnist Joyce Haber published the item in the spring of 1970, Seberg — the 31-year-old star of Jean-Luc Godard’s “Breathless” and Otto Preminger’s “St. Joan,” among other films — spiraled into a long-term depression that led directly to her suicide on a Paris street a decade later.

On its 50th anniversary, the story seems every bit as tragic as it was at the time, but also relevant again. This was an example, after all, of what can happen when unbridled power rests in the hands of irresponsible officials. It’s about the accountability and influence of the media, and the danger of dishonest, ad hominem attacks by government on individuals. It’s about the subversion of the rule of law.

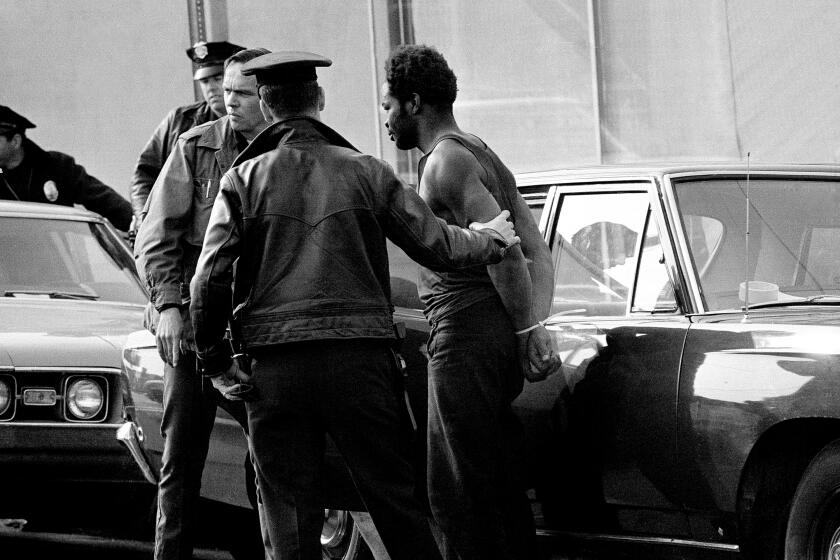

In the spring of 1970, the FBI was at the height of its war against radical movements in the United States. The bureau’s unscrupulous director, J. Edgar Hoover, had for years been working to undermine the antiwar movement, civil rights leaders and black militant organizations. Among the latter was the Black Panther Party, a group of self-styled revolutionaries challenging police brutality and white authority through “armed self-defense.”

Seberg was one of a number of Hollywood supporters of the Panthers. She had donated more than $10,000 and may have been in a relationship with one of its members (leading the bureau to describe her internally as a “promiscuous and sex-perverted white actress”). On April 27, a cable was sent from the FBI’s Los Angeles office to Hoover requesting permission to “publicize the pregnancy of Jean Seberg, well known actress, by [name deleted] of the Black Panther Party by advising Hollywood gossip columnists.” The cable said this could “cause her embarrassment and serve to cheapen her image.”

Headquarters responded: “Jean Seberg has been a financial supporter of the BPP and should be neutralized.”

When the tip came in, a Times reporter passed it to the Metro editor, who sent it on to gossip columnist Haber. She ran the item on May 19 with no names attached — but with enough details that Seberg was easily identifiable. In it, Haber noted that Seberg, whom she called “Miss A,” was “pursuing a number of free-spirited causes, among them the black revolution.” Haber said that the father of her child was “said to be a rather prominent Black Panther.” A similar item ran in Newsweek a few weeks later, this time using Seberg’s name.

The information was malicious, manipulative and most likely untrue. Certainly the FBI didn’t know if it was accurate (it leapt to a conclusion based on transcripts of a wiretapped call) and neither did The Times. Seberg and her family always denied it.

SWAT’s first L.A. operation was a shootout with the Black Panthers. Race has lingered in America’s increasingly militarized policing ever since.

But in an era when a relationship between a married white woman and a radical African American lover would have been frowned upon in many circles, the assertion was devastatingly effective. The result, as Jon Wiener and Mike Davis put it in their new book, “Set the Night on Fire,” about L.A. in the 1960s, was “a cascade of disaster.” Seberg went into premature labor in August; the baby died two days after delivery. Seberg became depressed, her career stalled, and she tried repeatedly to commit suicide. In 1979, she was found dead in her car on a Paris street after intentionally overdosing.

Although it is difficult to say what combination of factors leads a person to suicide, her ex-husband said at a news conference after her death: “Jean Seberg was destroyed by the FBI” when the bureau gave “a large American newspaper” inaccurate information.

Just a few days after that, the FBI acknowledged its role. (Hoover by that time was dead.) Among other things, the bureau said: “The days when the FBI used derogatory information to combat advocates of unpopular causes have long since passed. We are out of that business forever.”

Of all the agency’s Nixon-era excesses, those undertaken as part of Hoover’s counterintelligence program, known as COINTELPRO, seem particularly villainous. In the Seberg case and many others, COINTELPRO operatives went beyond gathering intelligence or arresting lawbreakers to actively spreading false and derogatory information to discredit, divide and disrupt politically disfavored groups.

Whether true or false — and the evidence suggests it was false — the FBI’s tip should never have been published. Why was The Times publishing irrelevant, unsourced, unchecked gossip on people’s sexual and marital activities at the behest of the FBI, and especially in such a racially charged manner? Shame on us.

The story is relevant today because we’re living through another era in which American democracy is in peril. There is no reason to believe that President Trump has unleashed his intelligence agencies the way Nixon did. But Trump is a leader whose dishonesty has been established and who puts his own interests ahead of the integrity of the U.S. government. He has been contemptuous of the rule of law.

What’s more, he traffics in unfounded attacks and conspiracy theories — and he doesn’t need an FBI director or compliant newspaper editor to spread them; he can push them out to his 80 million Twitter followers himself. In recent weeks, Trump has baselessly accused TV host Joe Scarborough of murder.

There have always been leaders who see their own personal ambitions and grievances as more important than the democratic process. As election day approaches, remember: We’ve been down this road before and we don’t want to go there again.

@Nick_Goldberg

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.