One lesson from the Weinstein case is that men like me must speak out about abuse

- Share via

Last month, as a new sex crimes trial began for Harvey Weinstein in Los Angeles, defense attorney Mark Werksman insisted that Weinstein was falsely accused by women and was the victim of the #MeToo movement.

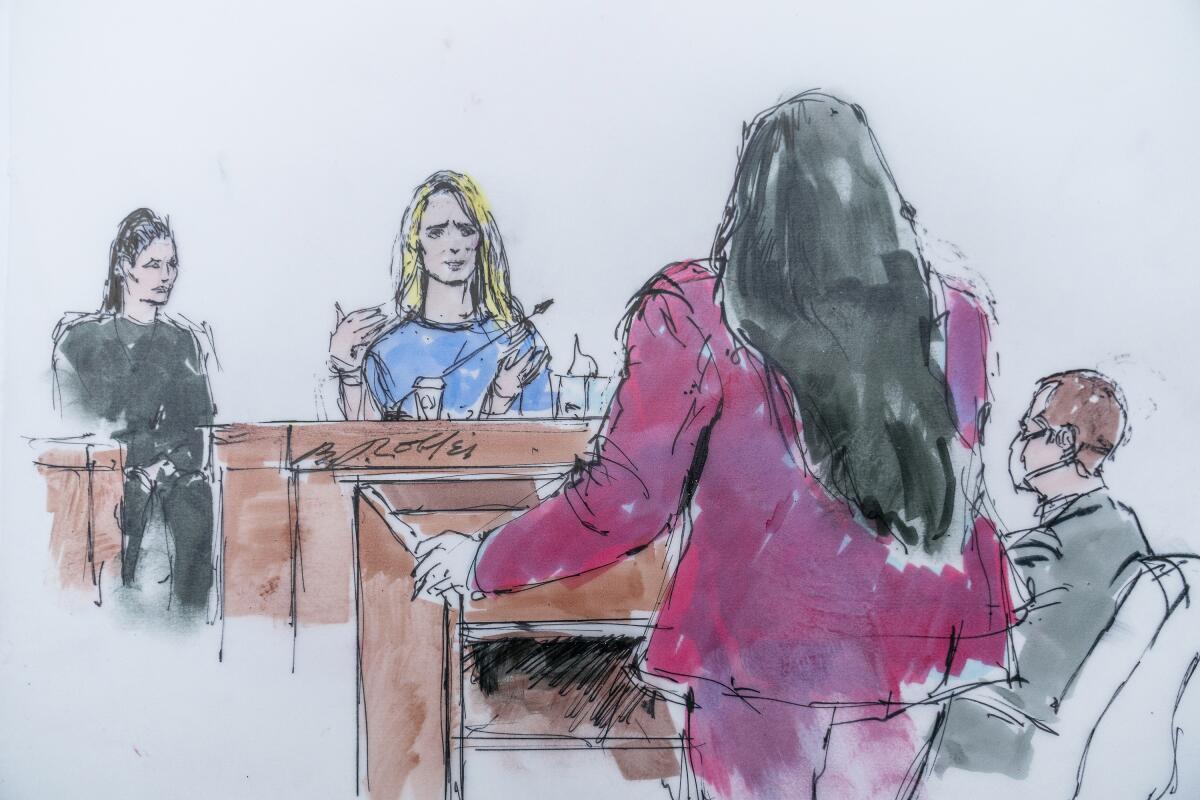

During opening arguments, Werksman attacked California First Partner Jennifer Siebel Newsom as “just another bimbo who slept with Harvey Weinstein to get ahead” while claiming others had either “made up” the assaults or engaged in transactional sex. After Siebel Newsom testified in court that Weinstein raped her, Weinstein’s attorneys claimed that she “indicated [her] pleasure.” He even asked her to re-create a faked orgasm in court.

I admire Siebel Newsom and other brave women who have called out Weinstein’s crimes — especially considering my own initial misgivings about coming forward and my fear of him, when I had far less to lose. I was the accountant for both Miramax and the Weinstein Co. for 28 years, and I became aware of a pattern of accusations against Weinstein in late 2014, a few years before they broke into a public scandal.

Seeing his defense in court, I can tell you Weinstein hasn’t changed one bit: He has used intimidation for decades against women to try to discredit and silence them. It shouldn’t have worked for as long as it did.

The onus to speak out against Weinstein and predators like him should not solely be on survivors. Men in positions like mine can and must help by exposing the sexual misconduct of their peers, co-workers and bosses and ensuring that abusers are exposed and held accountable.

Looking back, I know I should have publicly spoken up sooner when it was clear the board would do nothing. Though I didn’t know the full extent of his abuse, I tried to work internally in the company to stop him starting in 2014, and I came forward publicly only after reporters from the New York Times contacted me in 2017. They had been alerted by survivors of the abuse, who showed the courage no bystanders had displayed.

I was an unlikely source on the pervasive sexual abuse by one of the most powerful people in Hollywood. I began working as an accountant for Miramax in 1989. For years, I had heard rumors of sleazy behavior involving Weinstein. I wrote these reports off as him being a womanizer. However, as I began to grasp the depravity and extent of his behavior, and after dozens of women publicly accused Bill Cosby of sexual assault, I came to see these accounts as a disturbing pattern that was certain to continue. My daughter Shari, then 25, insisted that I act. She made clear that it would be cowardly to remain silent. She was right.

Initially, I tried to confront Harvey and to work within the Weinstein Co. to rein in his behavior. In November 2014, I sent an email to Weinstein imploring him to “[s]top doing bad shit.” He confronted me the next day and, although he admitted nothing, referred to me disparagingly as “the sex police” from then on out. I, and other executives, also tried to persuade his brother, Bob Weinstein, and several board members to force Weinstein to leave the company.

Instead, the company gave Weinstein a new contract that included a payment structure to punish him if the company entered into settlements to compensate victims of his abuse. Under that deal, Weinstein would cover the costs of future settlements and pay a $250,000 financial penalty for his first offense, with escalating penalties. This sickening “incentive structure” condoned Weinstein’s bad behavior and made clear that he was there to stay.

The men controlling the company chose complicity over the safety and dignity of women whom Weinstein preyed upon. However, once some women who had been abused by Weinstein showed the courage to come forward to the New York Times, I knew I had to take a risk and do the same. I gave those reporters inside information about old and new accusations against Weinstein, and Weinstein responded by trying to bully me into silence with false accusations.

Men have a critical role to play in ending sexual assault, harassment and misconduct. As men constitute the majority of business leaders, including directors of boards, they are often well-positioned to use their power to hold other men accountable, to help survivors and to ensure that more misconduct does not occur. By not believing survivors or failing to take adequate action, men have too often enabled individual actors and systems that perpetuate sexual abuse. Accountability for Weinstein came only after countless men and some well-known women had enabled Weinstein’s behavior for decades.

I don’t know whether the abuse would have ended sooner if I had alerted someone outside the company in 2015.

Weinstein’s new criminal trial is happening five years after the #MeToo movement ignited, and I hope that the defense’s victim-blaming tactics will fail in this era. Regardless, they are indicative of the attacks and trauma women continue to face for telling the truth. Survivors bear enormous burdens. They should not have to speak out alone too. Men in positions like mine can and must bolster that truth.

When pushed by my daughter, I did speak up to the board eight years ago and help the reporters’ investigation five years ago. Today, I recognize that silence in the face of abuse is complicity.

Irwin Reiter was the executive vice president of accounting and financial reporting at the Weinstein Co.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.