Trump’s national monument plan could easily fail — but he’ll still declare victory

- Share via

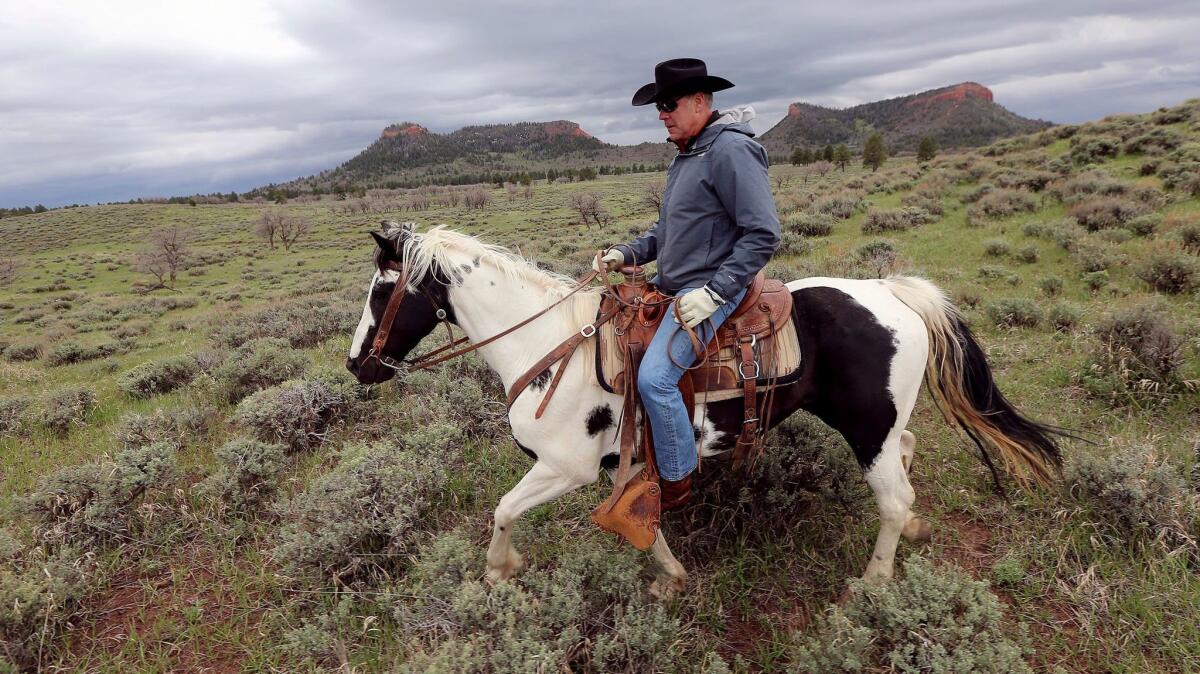

Washington — Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke tangled with protesters, weaved through media hives and trotted on horseback across a Utah moonscape this week in pursuit of President Trump’s executive order targeting national monuments.

It’s a directive that may prove legally tenuous but is nonetheless creating rich political theater for the White House.

Trump struggled during the campaign in deeply Republican Utah, particularly with its politically potent landowner rights movement. But now the Queens-born president is polishing his bona fides with that crowd by dispatching a rugged Cabinet secretary on a quest that is rankling environmentalists and Native American tribes.

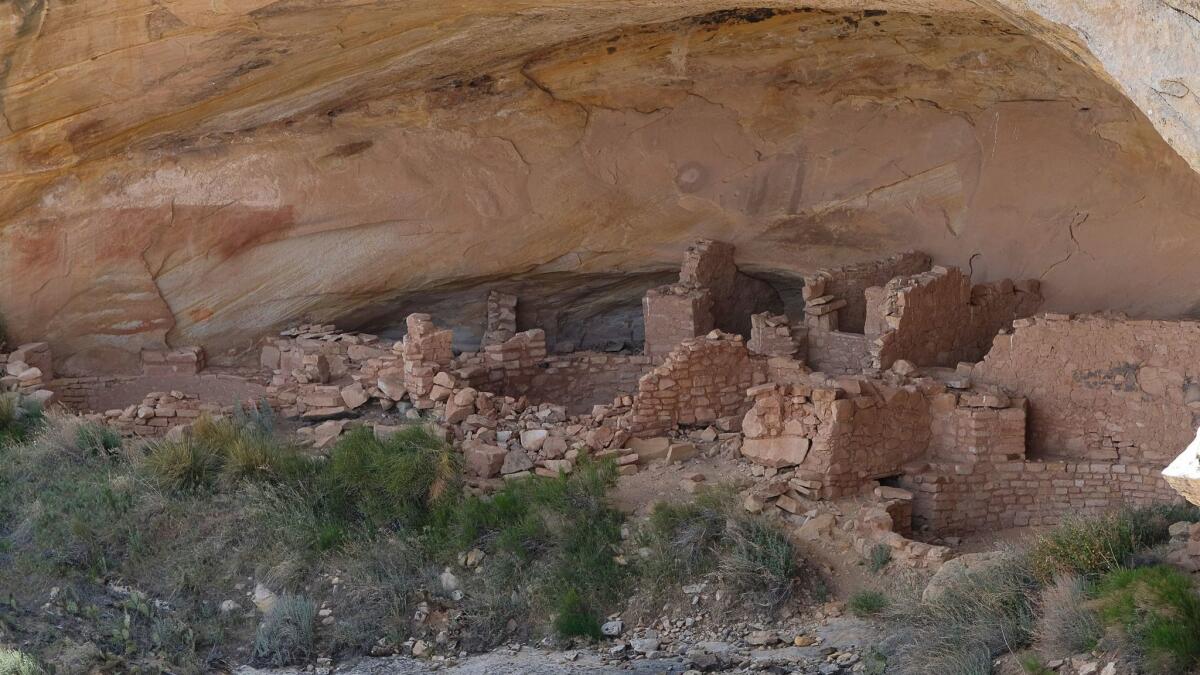

Over four days ending Wednesday, Zinke is surveying two hotly contested monuments: the 1.35-million-acre Bears Ears, which President Obama established at the behest of tribes and conservationists in the final weeks of his administration, and the 1.9-million-acre Grand Staircase Escalante, which has riled local developers and energy companies since President Clinton created it in 1996.

In the hardscrabble communities nearby, these monuments are often derided as a “betrayal,” depriving them of potential jobs from energy extraction and other uses. Utah Sen. Orrin Hatch invoked the word yet again recently while railing against the Bears Ears designation on the Senate floor.

The administration’s campaign against monuments was launched in Utah by design. The state is a hotbed of resistance to federal control of land. It has even passed a law calling on the federal government to cede control of most of its vast holdings to the state.

“They are trying to work with a favorable audience,” said Rep. Raul Grijalva of Arizona, the ranking Democrat on the House Natural Resources Committee. “Once they leave the confines of Utah and start looking at all those other monuments, the politics dramatically changes.”

Attorneys general in New Mexico and Washington warned Zinke in recent days he has no authority to diminish their monuments, and California would not hesitate to engage in a fight should Zinke move on lands within its borders.

Even in Utah, polls show the public is divided on whether the Bears Ears designation should be rescinded. But the state’s political leadership is largely united, and Zinke is getting his fill of attaboys on this trip.

“We now have an opportunity to discuss and deliberate like we didn’t even have during the Bush administration,” said Ken Ivory, a Utah legislator who is leading a multi-state federal land push that would go much further than Trump’s executive order. Ivory’s crusade, which has a number of allies in Congress, seeks to export nationally the Utah approach of pushing the federal government to transfer its land to state control.

It’s a sensitive political issue for Trump and Zinke, who are aligned with a large coalition of hunters, anglers and outdoor outfitters anxious about what states would do with the federal land. Both men consider themselves outdoorsmen and have made assurances the Trump administration will not be relinquishing federal control of the millions of acres at issue. But Ivory is nonetheless encouraged by the move against the monuments. “This will continue the discussion,” he said.

The protected lands Zinke came to survey are at the core of Trump’s order for a review of all monuments created since 1996 that are larger than 100,000 acres, which is ultimately expected to end with Zinke suggesting both areas either get stripped of the monument designation altogether or be downsized substantially. Zinke is in a race to review those and 19 other monuments, including six in California, before producing two lists of suggested eliminations and rollbacks. He will present the first list in mid-June.

There is ample evidence the exercise could go sideways, as some of Trump’s other executive orders have. Trump’s ban on visitors from six predominantly Muslim nations and his bid to punish sanctuary cities are both unraveling in court. The executive order Trump vowed would force builders of the Keystone XL oil pipeline to use American steel actually won’t.

The review of these monuments is predicated on the idea that the president has this authority that he doesn’t have.

— Kate Kelly, advisor to former Interior Secretary Sally Jewell

“The review of these monuments is predicated on the idea that the president has this authority that he doesn’t have,” said Kate Kelly, who was an advisor to former Interior Secretary Sally Jewell. “There is no legal basis for it.”

The last time a president moved to get rid of a monument on his own authority was in 1938, when Franklin D. Roosevelt sought to jettison the Castle-Pinckney National Monument in South Carolina. His attorney general looked into options at the time and reported back that Roosevelt couldn’t do that. It would take an act of Congress, which ultimately authorized the federal government to offload the property in the 1950s. The president’s authority to undo monument designations, environmentalists argue, has only shrunk since the Roosevelt administration, after Congress passed laws solidifying the federal protection.

Attorneys affiliated with some of the conservative think tanks influential in guiding Trump’s agenda argue the Roosevelt administration got it all wrong. They say that not only does the president have explicit authority to scotch monuments, but that many of the monuments created under the century-old Antiquities Act were done so illegally. The act, their argument goes, was never intended to preserve sprawling land masses the size of Delaware.

By this line of reasoning, even Teddy Roosevelt was out of bounds when he designated the Grand Canyon a national monument. (It has since become a national park, and thus universally agreed to be untouchable by Trump’s executive order).

“I think the president is in a strong position,” said Todd Gaziano, an attorney at the Sacramento-based Pacific Legal Foundation, a conservative advocacy group.

While no president has ever successfully eliminated national monuments, several have changed their shapes, and even shrunk them. John F. Kennedy substantially redrew the boundaries of the Bandelier National Monument in New Mexico, shaving off nearly 4,000 acres and adding 3,000, saying the borders of what needed to be preserved had evolved. When Olympic National Park in Washington was still a monument, it was reduced in size multiple times to enable timber harvesting, including in 1915 when logs were needed to build Navy ships for World War I.

But there was a big difference between those parings and the ones Trump may be on the verge of trying to make now: the earlier presidential moves to redraw monument boundaries were not contested. The courts have yet to weigh in on whether the president can take such action when stakeholders such as American Indian tribes, environmental groups and lawmakers vehemently object.

Those groups have made clear that they won’t let Trump lift protections off a single acre of monument land without a bitter court fight.

Justin Pidot, a former deputy solicitor general at the Interior Department who now teaches law at the University of Denver, said if he were working for this administration he would be warning Zinke that the legal arguments are shaky. But, Pidot allowed, that may not be an overriding concern in this case.

“A lot of things this administration does, it does for political theater,” he said. “They can say they have done them, and then they get to rail against the courts for stopping them.”

Follow me: @evanhalper

ALSO

PHOTOS: ‘Super bloom’ at Carrizo Plain National Monument

Snowmelt triggers a flood warning in Yosemite and a river closure in the Central Valley

UPDATES:

7:55 a.m. May 12: This story was updated after some states warned the administration over Trump’s plan.

This story was first published May 10, 6:05 a.m.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.