Why debates have become an endangered species in California’s top races

- Share via

Reporting from Sacramento — California’s candidates for governor and U.S. Senate are infiltrating television, Facebook feeds and mailboxes with campaign ads and slick mailers, but there’s one place voters aren’t likely to see them — the debate stage.

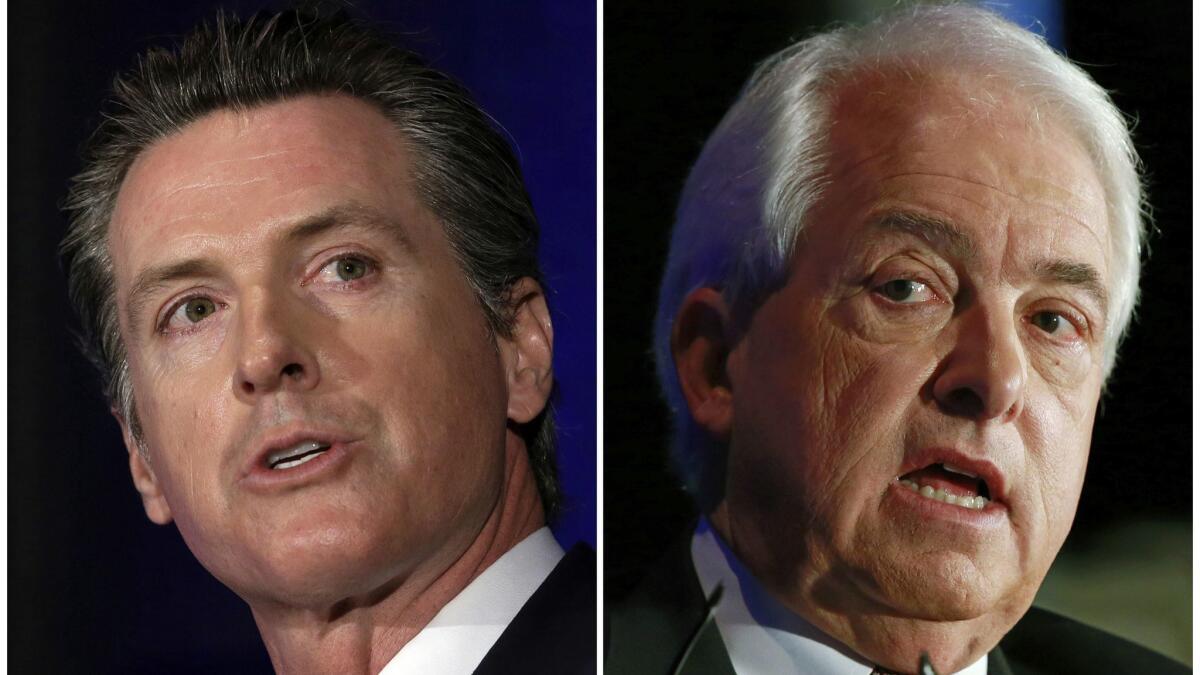

On Monday, a San Francisco public radio studio will be the venue for the lone gubernatorial debate — or “conversation,” as it’s been billed — between Democratic Lt. Gov. Gavin Newsom and Republican real estate investor John Cox. The faceoff won’t be televised, and the live radio broadcast will air at 10 a.m., during the heart of the workday.

No debate has been scheduled in California’s U.S. Senate race between Sen. Dianne Feinstein and state Sen. Kevin de León. But the two Democrats, who are in acrimonious negotiations on the topic, are expected to appear onstage together at least once before the Nov. 6 election.

Traditional electoral debates, which provide voters a side-by-side comparison of how candidates differ on the issues and respond under pressure, have become an endangered species in California’s general election campaigns of recent years. Since the dawn of the state’s top-two primary election system in 2012, in which the first- and second-place finishers advance to the November election, no race for governor or Senate has featured more than one debate between the two finalists.

Cal State Sacramento political scientist Kimberly Nalder said the effect of political debates has dissipated as voters have become more hardened in their political views. Debates have started resembling sporting events in which voters tune in more to support the candidate espousing their own political ideology than to learn about the individual politicians on stage, she said.

“I think there’s a growing cynicism about the utility of debates,” Nalder said.

That climate can be especially harmful to candidates for governor and Senate, who are usually less well known to voters than presidential hopefuls, Nalder said. “The bulk of California voters probably only have some vague idea of what Newsom might do. And he’s high-profile in California.”

Negotiations over staging debates are fraught with political gamesmanship. Front-runner Newsom enjoys a solid lead in the polls among the state’s left-leaning electorate, and he has little incentive to give Cox, who has never held elected office and is largely unknown to most voters, an opportunity to increase his visibility as the November election approaches.

California’s candidates for governor in standoff over debate schedule »

The Newsom campaign has opted against participating in more than one debate with Cox, turning down offers from a number of media outlets including the Los Angeles Times and the New York Times. Gov. Jerry Brown did the same in his 2014 race against Republican Neel Kashkari. In the 2016 U.S. Senate race, then-state Atty. Gen. Kamala Harris and fellow Democrat Rep. Loretta Sanchez also debated just once. Feinstein refused to take the stage even once with GOP candidate Elizabeth Emken in the 2012 Senate race.

There also has yet to be a single debate in one of California’s most pivotal congressional races, the Orange County matchup between GOP Rep. Mimi Walters and Democratic challenger Katie Porter.

The phenomenon is not unique to California.

In Maryland, Republican Gov. Larry Hogan agreed to a single debate with Democratic rival Ben Jealous after a lengthy standoff. And in Pennsylvania, Democratic Gov. Tom Wolf agreed to just one debate against Republican Scott Wagner, which was moderated by “Jeopardy” host Alex Trebek.

“If you’re the front-runner, the No. 1 rule is, don’t make a mistake that will transform the race and give your opponent an opportunity,” said Rose Kapolczynski, a Democratic consultant who ran campaigns for former U.S. Sen. Barbara Boxer.

Newsom campaign spokesman Nathan Click dismissed criticism of the candidate’s decision not to debate more than once ahead of the general election, saying Monday’s forum will be the 10th Newsom has participated in during the governor’s race, and the fifth time the lieutenant governor and Cox have shared a stage.

But those prior debates took place before the June primary, when there were six candidates sharing a stage, including Democrats Antonio Villaraigosa, the former mayor of Los Angeles, and state Treasurer John Chiang. In those forums, the candidates often had fewer than 15 minutes total to speak, as opposed to a more intense and illuminating one-on-one debate.

Newsom initially agreed to a televised debate hosted by CNN. But that arrangement fizzled once Cox demanded that it focus on housing, cost of living, water and other California-specific issues, which Newsom’s campaign said was an effort to limit the scope of questions asked.

After criticism from news outlets and others about the lack of debates, the two finally agreed to participate in a “gubernatorial conversation” hosted by San Francisco public radio station KQED. The event will be moderated by KQED’s senior politics editor, Scott Shafer, and air on radio stations throughout the state, including KPCC 89.3 FM and KCRW 89.9 FM in Los Angeles.

The forum gives Cox perhaps his best chance to make his mark. But the audience might be limited because the faceoff will take place on a federal holiday, Columbus Day, and will not be televised or aired during prime time. The radio audience also won’t be able to pick up visual cues that can be telling in a televised debate, including facial expressions and a candidate’s demeanor when under attack.

“This is John Cox’s moment to make his case to the undecided voters who are listening,” Kapolczynski said. “It’s probably one of the biggest audiences Cox is going to have during the campaign. So he’s going to be trying to create a moment that will capture public attention and be reported on later.”

Cox is expected to be the aggressor Monday. As has been a common theme of his campaign, the Republican is likely to attack Newsom for being part of a state Democratic leadership that has controlled Sacramento while poverty and homelessness exploded in the state, school quality declined and housing became unaffordable. Odds are high that Cox will also go after his rival for supporting the recently approved increase in gas taxes and what he calls “Bernie Sanders policies” such as a state-sponsored single-payer healthcare system.

Newsom didn’t hesitate to fire back when he was targeted by his opponents during the series of debates before the primary. The lieutenant governor almost assuredly will do his best to yoke Cox to President Trump, who has endorsed Cox’s campaign and remains extremely unpopular in California. The Newsom campaign also sees Cox’s opposition to abortion, as well as past controversial statements about gay rights and immigrants, as political vulnerabilities to be exploited.

But it’s doubtful that the forum will be as caustic as exchanges in some of the other high-profile candidate debates across the country. At a recent gubernatorial debate in Illinois, Republican Gov. Bruce Rauner went after his biggest threat for reelection, Democrat J.B. Pritzker, accusing him of being a “trust fund baby” who hasn’t done an “honest day’s work” in his life. Pritzker, in turn, called Rauner a “liar” and “failed governor,” among other insults.

“In California, debates tend to be a little more wonky in terms of issues compared to debates in other parts of the country, and they tend to be very polite,” said Bill Carrick, a Democratic political consultant who is advising Feinstein in her bid for a fifth full term in the Senate.

Feinstein hasn’t engaged in a debate with an opponent since the 2000 election, when she was opposed by then-Rep. Tom Campbell, a Republican.

Carrick promised that Feinstein will debate De León at least once before election day but said that “we’re not going to have 20 of them.”

“You can make the argument that one debate is more consequential than having 10,” he said. “It’ll get more attention.”

De León, who took part in a candidate forum with three other Senate candidates before the primary that Feinstein did not attend, has called for three general election debates in different areas of the state. He has agreed to several invitations from news and public policy organizations throughout California, campaign spokesman Jonathan Underland said.

“Eighteen years is too long,” Underland added, referring to the last time Feinstein took part in a debate.

Coverage of California politics »

Twitter: @philwillon

Updates on California politics

UPDATES:

10 a.m.: This article was updated to note that the debate will be broadcast on KPCC-FM in Los Angeles.

This article was originally published at 12:05 a.m. Sunday.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.