In his bid to be California’s next governor, John Chiang touts his battles with a previous one

- Share via

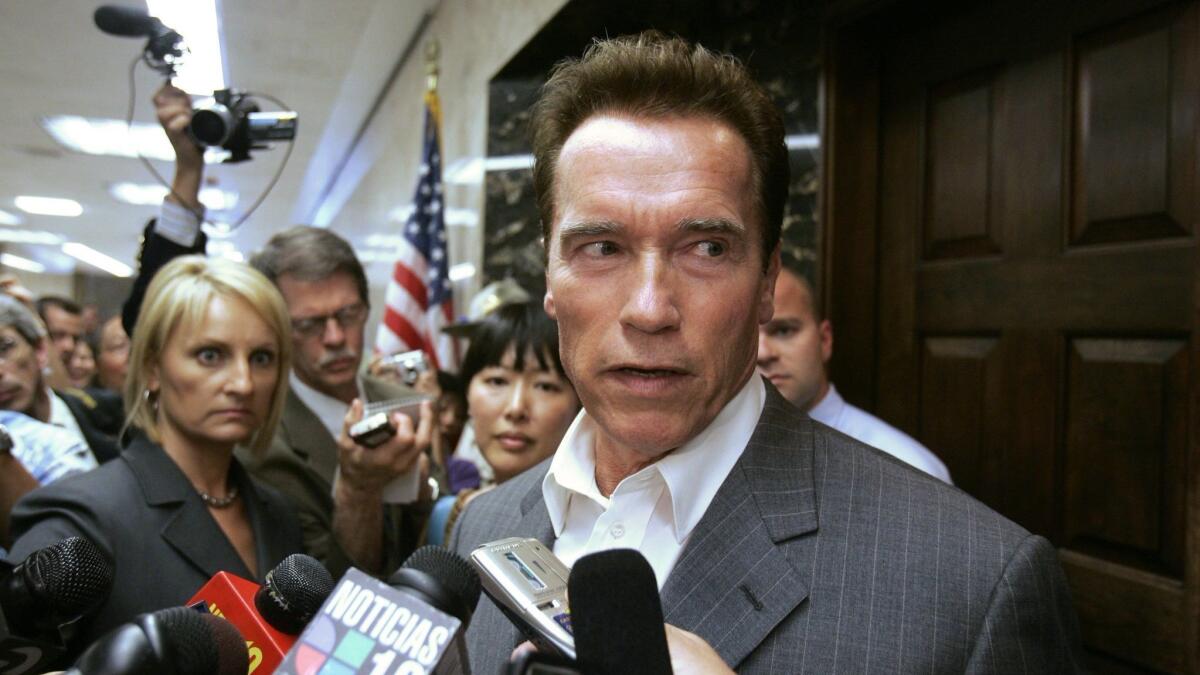

Reporting from Sacramento — As political matchups go, it was an incongruous one: the bodybuilder-turned-Terminator-turned-governor against the bespectacled numbers geek. One of the most famous men in the world versus — um, what’s that guy’s name again?

The 2008 showdown pitted then-Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger against John Chiang, California’s Democratic state controller at the time. The governor, facing a budget logjam, ordered a hefty cut in state worker pay to the federal minimum wage — then $6.55 an hour — but Chiang refused to comply.

That touched off a signature moment in Chiang’s two decades of elected office in California. His defiance set off a protracted legal battle, irked the Republican Schwarzenegger administration and won Chiang fans among powerful public sector unions.

It was a defining episode in Chiang’s political career, and one that suggested bigger political ambitions for the son of Taiwanese immigrants who once worked as an IRS tax lawyer.

The faceoff in his second year of what would be two terms as controller is now a central selling point in Chiang’s campaign to be California’s next governor, in which he has lagged in the polls. In an online ad, titled “Underdog,” Chiang, now state treasurer, touts his refusal “to let the governor cut the pay of hardworking Californians.”

The message to voters, Chiang said in an interview, is that he would similarly do battle for them.

The clash revealed Chiang’s canny ability to grab headlines while in a decidedly low-wattage post.

“Nobody has ever said that, ‘Since the age of 4, I always wanted to be state controller or state treasurer.’ It’s not normally a high-profile office,” said Daniel J.B. Mitchell, a state labor expert and professor emeritus at UCLA Anderson School of Management. “There are few moments where the opportunity comes along.”

Schwarzenegger’s plan to cut state worker pay was one such opportunity.

Treasurer John Chiang launches ad in governor’s race touting his record as a fiscal stewards here »

News of the proposal first surfaced in July 2008 when the Schwarzenegger administration floated a draft executive order that would temporarily pare back pay for about 200,000 state workers to the federal minimum wage. With a new state budget nearly a month overdue, the governor’s office said the move, which would have saved an estimated $1 billion each month, would keep the state solvent until a new spending plan was in place. At that point, the administration said, the workers would be repaid their lost wages.

Chiang, who issued state workers’ paychecks in his role as state controller, quickly lambasted the plan as cruel and illegal when it was first leaked to the news media. He said the state had plenty of cash to cover payroll, and he refused to go along, arguing in part that his office’s ancient computers would not be able to process the temporary salary adjustments.

The governor’s proposal was greeted with outrage from public employees and skepticism even from conservative corners, including the right-leaning editorial page of the Orange County Register, which called it a “minimally smart idea.”

But Schwarzenegger dug in, signing the order a week later and threatening to sue Chiang if necessary. The controller didn’t budge. Less than two weeks later, the governor took him to court.

The administration argued that, in the times of crisis, everyone had to feel the pain, including public employees. Others said the move had less to do with saving money and more to do with using public pressure to force legislators to agree on a long-delayed spending plan.

“What he was trying to do was force a budget settlement. That was his leverage,” Mitchell said. “Legislative Democrats would not want to see state workers cut to the minimum wage.”

Chiang says now he similarly saw the move as a budget negotiating tactic.

“It was a morally bankrupt act to get a Democratic Legislature to conform to the governor’s wishes,” he said.

Chiang’s refusal won praise from public employee groups, who allied with him in the court battles. Bruce Blanning, then the executive director of the Professional Engineers in California Government, said Chiang distinguished himself from other Democrats by challenging the governor.

“Schwarzenegger intimidated a lot of people. He did not intimidate John Chiang,” said Blanning, who still consults for the state engineers union, which has supported Chiang’s campaign.

Inside the administration, the view of Chiang was negative. One former Schwarzenegger official, who requested anonymity to speak candidly, said he was seen as brown-nosing to a powerful Democratic interest group, hardly qualifying as political courage.

“It’s like saying someone in Congress is standing up for pharmaceutical companies,” said the official, who is no longer in state government. Public employee unions “are the most powerful political player in the state. It’s not like standing up for widows and orphans here.”

Chiang rejected that characterization, instead focusing on the low-wage workers who would have been impacted by the plan.

“I don’t think the administrative assistant or the student intern or all these individuals feel attached to a politically powerful institution,” he said. “These are individuals who are trying to pay for their electricity bill, their tuition.”

The standoff was rendered moot by September, when Schwarzenegger signed a new state budget deal — 85 days late. Still, the issue lingered undecided in the courts.

The two men would soon clash again over a new order by the governor mandating that state workers take two unpaid furlough days a month in order to save money.

Chiang, again siding with labor unions, said he would not comply. He later argued the furloughs should not apply to his office and those of other statewide elected officials, because they are independent of the governor. Schwarzenegger once again sued. The liberal-leaning Sacramento Bee accused Chiang of “pandering to employee unions.”

The California Supreme Court ultimately upheld the furloughs but said future governors would not have unilateral authority to impose unpaid days off. A separate appeals court ruling found that Schwarzenegger did have the power to furlough the workers of elected statewide officers.

Meanwhile, the worker-pay fight continued in the courts, with Schwarzenegger initially prevailing. The governor again tried to reduce state workers’ salaries to the federal minimum wage in 2010. The cuts were never put into place, although an appellate court also sided with Schwarzenegger.

When Gov. Jerry Brown took office in 2011, he decided to drop the lawsuit, arguing it would be too costly, according to news accounts.

“It was a close call on the furloughs and on the minimum wage, legally,” Blanning said. “But he said, here’s what I think is best for California, and here’s what my job is as controller.”

The state engineers union has issued a dual endorsement in this year’s governor’s race to Chiang and to Lt. Gov. Gavin Newsom, another Democrat who is the front-runner in the race, according to numerous polls ahead of the June 5 primary. The group, which represents 13,000 workers, contributed just under $15,000 to Chiang’s and Newsom’s respective campaigns.

Despite Chiang’s fight for state workers, the state’s largest public employees union has not backed his gubernatorial bid.

Alex Arnone, spokesman for Service Employees International Union Local 1000, called Chiang’s stance in the minimum-wage tussle “the right thing to do at the right time,” but the group, along with the statewide SEIU council, instead endorsed Newsom — the result of what Arnone called a “thorough member engagement process” of all SEIU members statewide.

Chiang maintains that he has “widespread support” from that union’s members.

And as for his old sparring partner? Chiang said that despite the friction, he wishes Schwarzenegger well.

“I disagreed with him passionately and vehemently on issues,” Chiang said. “But I do have respect for people who give portions of their life for the betterment of our state and our humanity.”

Follow @melmason on Twitter for the latest on California politics.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.