Two top candidates for California governor have been touting their healthcare wins. Here’s what they really did

- Share via

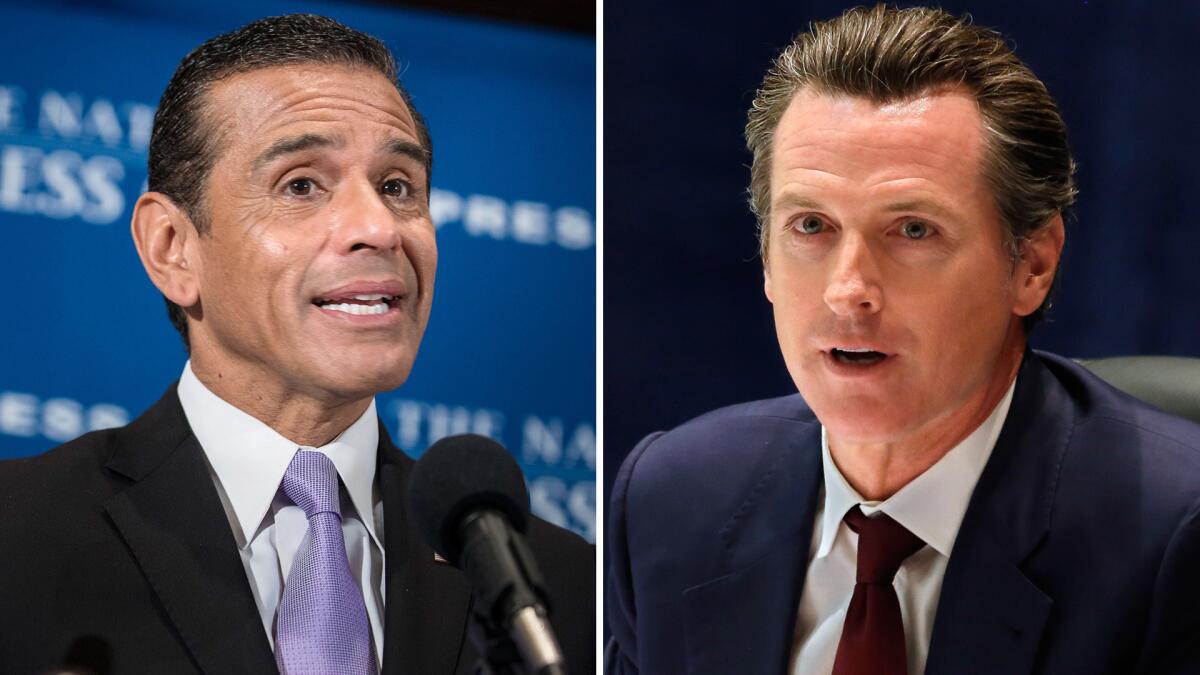

Reporting from Sacramento — Gavin Newsom and Antonio Villaraigosa are depicting themselves as Democratic healthcare visionaries as they campaign to become California’s next governor.

To prove his healthcare mettle, Newsom points to Healthy San Francisco, a first-of-its-kind universal system adopted while he reigned as the city’s mayor in 2006. Newsom’s work on the program helped him land an endorsement from the influential California Nurses Association, and a boast or two will surely punctuate his speech at their convention on Friday as hyper-partisan politics intensify over efforts to repeal the Affordable Care Act and implement a national single-payer plan.

Villaraigosa holds up the creation of Healthy Families, legislation he authored as a state assemblyman in 1997 that provided coverage for the children of California’s working poor.

Both programs are considered successes, benefiting the lives of tens of thousands of Californians. While the two Democratic candidates played pivotal roles, Newsom and Villaraigosa were not the sole inspiration for the programs they now cite as their signature achievements on healthcare. And some will not let them forget it.

That includes former San Francisco County Supervisor Tom Ammiano, author of the ordinance that evolved into Healthy San Francisco. His resentment about Newsom taking credit for the program is still palpable.

“He was very nervous about [the program] and tried to undermine it as best he could,” Ammiano told the Los Angeles Times recently. “He did sign it, and since then he’s been taking credit for it.”

The two candidates, who along with state Treasurer John Chiang are among the most widely known in the race, have also been quick to take shots at each other over their roles in the creation of the programs.

“Gavin came in kicking and screaming,” Villaraigosa, the former mayor of Los Angeles, said of Newsom’s support for Healthy San Francisco.

Newsom brushed aside Villaraigosa’s work on Healthy Families, saying all it really did was funnel federal money for children’s healthcare to California counties, including San Francisco, that implemented the coverage.

“It was table stakes,” said Newsom, who is currently the state’s lieutenant governor. “It was something all of us were well positioned to do. And would have been foolish not to do.”

Their posturing also shows these seasoned politicians understand how hot the healthcare issue is in California.

When California voters were asked about how they’ll rank issues while they’re considering which gubernatorial candidate to support in 2018, healthcare finished second only to jobs and the economy, according to a recent poll by the UC Berkeley Institute of Governmental Studies.

At a recent campaign stop in Fresno, an audience member asked Newsom what his healthcare policy would be if he won.

“What can we do ourselves?” Newsom said after a brief discussion about rising healthcare costs. “Well, I asked that same question as mayor of San Francisco. And everyone said, well a city can’t do healthcare. Only states or countries [can do that]. And I said, ‘Well, I don’t know about that.’ ”

In 2006, San Francisco became the first city to launch its own universal healthcare system, a program that at its peak provided affordable care to more than 70,000 uninsured residents in the city. The program gives members access to a primary and other care. It is funded by the city through income-adjusted patient co-pays and fees paid by San Francisco employers with uninsured workers.

“San Francisco has universal healthcare — regardless of preexisting conditions, regardless of your ability to pay and regardless of your immigration status,” Newsom told the crowd gathered in Fresno.

Newsom expressed concerns about the proposed ordinance that eventually became Healthy San Francisco. He worried about the impact of the fees on city businesses, according to San Francisco Chronicle story published after the initial ordinance was introduced in 2005.

When interviewed this week, Newsom argued that Ammiano’s idea amounted to a health insurance program that failed to cover most of San Francisco’s uninsured. Newsom said he authored a separate proposal focused on providing direct care, not insurance, to everyone without healthcare coverage in the city.

Mitchell Katz, who served as San Francisco’s director of the Department of Health Services Health Services when Healthy San Francisco was created, described the ultimate result as a compromise: Ammiano wanted to require employers to pay for or provide healthcare for their workers, and Newsom was pushing for a city-controlled universal healthcare system.

Healthy San Francisco enrollment dropped dramatically after the passage of the Affordable Care Act, also known as Obamacare, which provided insurance to many of the residents in the city program. The program currently serves about 14,000 people.

Though Villaraigosa authored the legislation that created the statewide Healthy Families, that program was also born out of political compromise.

Villaraigosa, who had authored legislation to expand Medi-Cal coverage for children, proposed doing the same with a new bushel of federal funding targeted at healthcare coverage for children. But Republican then-Gov. Pete Wilson refused, insisting that families should pay at least something based on their income to cover their child’s healthcare rather than receive care under Medi-Cal for free.

“Wilson told me straight to my face that he’d never do it,” Villaraigosa said.

Kim Belshe, who was Wilson’s state health director, credits Villaraigosa, who was the Assembly’s majority leader, for helping craft a compromise and convincing Democrats to support it.

Wilson signed the Healthy Families into law in 1997, which at the time created a $500-million program offering subsidized health insurance to more than 580,000 California children whose families were uninsured but earned too much to qualify for Medi-Cal, California’s health care program for the poor.

After Healthy Families passed, Villaraigosa vowed to expand it into a universal healthcare program for 5.5 million California adults who were uninsured. But that never happened because of cost concerns, and in 2013 Healthy Families was folded into Medi-Cal as a cost saving measure.

Now both Newsom and Villaraigosa say they support the push for a national single-payer system. But they diverge over whether California should go solo and launch its own state-sponored program — a plan the California Nurses Association lobbied heavily for this year in the California Legislature. That plan was also shelved mostly due to cost concerns.

Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders, champion of the Democratic movement for a national single-payer system, will be at Friday’s California Nurses Association conference to preach his Medicare-for-all gospel. Newsom is scheduled to speak just hours before him.

Villaraigosa said the estimated $400-billion price of this year’s state proposal made it unaffordable and the Trump administration would never grant the federal waivers needed to make it feasible. Newsom, who had indicated he favored the proposal, said he’s “committed to advancing that debate” on a state single-payer plan, but has stopped short of offering his iron-clad support.

Both agree that California needs to take action soon.

If President Trump and Republicans in Congress repeal Obamacare, Villaraigosa says, the state must first grapple with a potential loss of tens of billions in federal healthcare funding. He has floated the idea of allowing Californians to buy into Medi-Cal.

Newsom said he is trying to determine which aspects of the Healthy San Francisco program could be replicated statewide.

“We’re about to potentially get hit with a major, major shock to the system,” Newsom said.

Twitter: @philwillon

Updates on California politics

ALSO:

Trump presidency eases Gavin Newsom’s path in his second run for California governor

Turning aside risk, Democrats rally to Bernie Sanders’ single-payer health plan

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.