With new allies and approaches, California lawmakers try again to confront high prescription drug prices

- Share via

Reporting from Sacramento — Less rowdy than the sputtered push for single-payer healthcare and less fraught than the battle over Obamacare’s future, the concern over the cost of prescription drug prices has been overshadowed for the past year by the marquee healthcare battles gripping Sacramento and Washington.

That’s not likely to be the case much longer. The effort to rein in pharmaceutical costs is poised for a major showdown as state lawmakers enter their final month of the legislative year.

The debate conjures déjà vu. Much of the action centers on legislation that recalls a failed 2016 bill to require more disclosure around prescription prices, with lobbying efforts tracing familiar battle lines — labor unions, health plans and consumer groups facing off against drug manufacturers.

But several new factors this year have made proponents bullish about their prospects. The price disclosure bill , SB 17 by state Sen. Ed Hernandez (D-Azusa), is now one of five measures that have been proposed to tackle prescription costs, forcing the drug industry to fend off multiple threats. Supporters have picked up new allies on the left, including deep-pocketed Democratic activist Tom Steyer, and on the right, with “aye” votes cast by a handful of GOP lawmakers.

The issue remains fresh. Over the last few years, high-profile stories have captured the public’s attention, such as the legal saga of convicted pharmaceutical executive Martin Shkreli and the steep increase in the price of EpiPens, which are commonly used to ward off severe allergic reactions.

“Each consecutive outrage and story just creates some urgency, if not inevitability, that something needs to be done,” said Anthony Wright, executive director of Health Access California, an advocacy group.

‘Pharma Bro’ Martin Shkreli calls securities fraud conviction ‘a witch hunt of epic proportions’ »

Around $320 billion was spent in the U.S. on prescription drugs in 2015, according to the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. After relatively slow growth in drug spending in the early 2000s, spending surged by 12.4% in 2014, mostly due to expensive new specialty drugs hitting the market. In 2015, spending grew at a lower rate of 9%.

Hernandez has pitched his measure as a way to better understand what’s driving that spending. His bill would require health plans to report to the state the 25 drugs that are most frequently prescribed, those that are most costly and those that have had the highest year-to-year increase in spending.

The measure also would require drugmakers to provide notice to health plans and other purchasers 60 days in advance of a planned price increase, if the hike exceeds certain thresholds.

Manufacturers have chafed at the proposal, arguing that requiring disclosure of list prices — the full sticker cost set by drugmakers — distorts what’s actually being paid by health plans and other big purchasers, which can negotiate discounts, and by consumers, who frequently make use of drug rebates and coupons.

“This bill is really just a way to shame the industry on list prices, which in no way reflect the actual cost of drugs,” said Brett Johnson, senior director of policy and regulatory affairs for the California Life Sciences Assn. “Clearly, those who are trying to use this misleading information want to use it in a shaming way, putting our industry in a negative light.”

Drug companies, which raised more than $100 million to defeat a 2016 ballot measure to cap what state agencies could pay for drugs, said they’re not shying away from the affordability question.

“We want to talk about costs. We want to find solutions for patients,” said Priscilla VanderVeer, deputy vice president of public affairs for Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America. “We continue to struggle with: What is the outcome of this [measure] and how will it help patients? How does it truly affect what happens in the marketplace?”

Hernandez, who is running for lieutenant governor in 2018, said that when he offered a similar bill last year, pharmaceutical companies did not engage with him, focusing instead on killing the measure.

“To their credit, this year, not too long ago, they said, ‘let’s talk,’ ” Hernandez said. But the discussions, which hinged on drug companies seeking broader confidentiality protections, failed to yield an agreement.

“I’m willing to have a conversation, but what I’m not willing to do is gut the bill so much or alter it so much that it doesn’t do anything,” Hernandez said.

The measure is backed by an array of state Capitol heavy hitters, including health insurers and unions such as the California Labor Federation. New to the cause this year is Steyer, whose group NextGen America will spend six figures on digital ads and direct mail to advocate for the bill.

Drug companies “don’t even believe there should be transparency,” Steyer said. “The level of their arrogance is astonishing.”

The bill also picked up some support from Republicans, who have typically been aligned with drug companies. Two GOP state senators, Scott Wilk of Santa Clarita and Andy Vidak of Hanford, voted yes on the measure when it cleared the Senate in May.

“Health care costs are becoming an increasing part of a family’s budget, of employers’ costs and of government expenditures,” Vidak said in a statement. “Price reporting transparency by all sectors of the health care system will help patients, providers and taxpayers.”

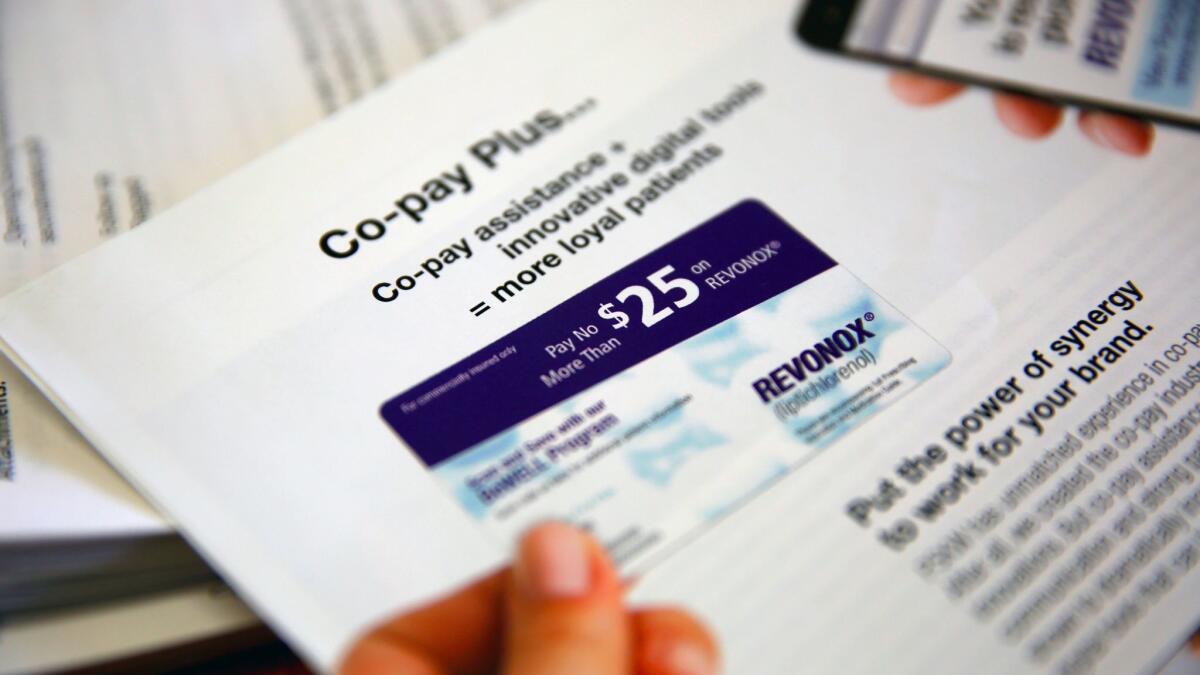

Drug companies have also mobilized against AB 265, a measure by Assemblyman Jim Wood (D-Healdsburg), which would limit when manufacturers could offer rebates or discounts for brand-name drugs when generic alternatives are available. The measure includes exemptions for certain HIV/AIDS drugs or when patients have gotten authorization for brand-name drugs from their health plans.

The bill was inspired by research that found that such coupons, while lowering consumers’ out-of-pocket costs, contribute to high overall healthcare spending by enticing customers to stick with pricier versions of their medication.

But some groups representing patients have assailed the bill as a government intervention into medical care.

Decisions on what type of treatment to prescribe “need to be left for the physician, not for our state Legislature to make,” said Liz Helms, president of the California Chronic Care Coalition.

In another measure, AB 315, Wood aims to tackle a different part of the drug supply chain: pharmacy benefit managers, or PBMs, which act as intermediaries between drugmakers and purchasers, such as health insurers.

PBMs, such as Express Scripts or CVS Caremark, tout their ability to negotiate steep discounts with manufacturers to pass on savings to consumers. But drug companies have long argued that these middlemen have operated with minimal scrutiny, leading to little accountability for their promises.

Wood’s bill would require pharmacy benefit managers to register with the state and disclose upon the purchaser’s request information about their dealings with manufacturers, such as drug acquisition costs and the amount they’ve received in rebates and administrative fees.

The Pharmaceutical Care Management Assn., an industry trade group, has opposed Wood’s bill as a costly mandate.

Spokesman Greg Lopes said the bill “would impose the kind of transparency that the Federal Trade Commission and economists say will increase costs by giving drug companies and drugstores unprecedented power to tacitly collude with competitors and raise prices.”

But Wood said more transparency is necessary in a healthcare sector in which all industry players are quick to cast blame elsewhere.

“Everybody says, ‘We’re the good guys,’ ” Wood said, exhorting companies to show the data to back up their claims. “If you are the good guys, why would you fear us looking at the information? Why would you fear us understanding your business model?”

Other related measures include SB 790 by Sen. Mike McGuire (D-Healsburg), which would place new restrictions on gifts from manufacturers to physicians, and AB 587 by Assemblyman David Chiu (D-San Francisco), which would require state agencies to convene regularly to identify ways to address rising drug costs.

The bills are not explicitly connected. Many advocates said it was a happy coincidence that several lawmakers all wanted to tackle the issue of drug pricing this year. But they say it offers a handy counter to opponents who argue any one bill is insufficient.

“It does diffuse the argument that this doesn’t really solve the real issue,” Wright said, “because we can point to [the] other bills.”

Follow @melmason on Twitter for the latest on California politics.

Voter anger over surging prescription drug costs has generated a campaign issue

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.