Column: Schools, cities and counties will ask California voters to OK taxes and borrowing totaling $20 billion

- Share via

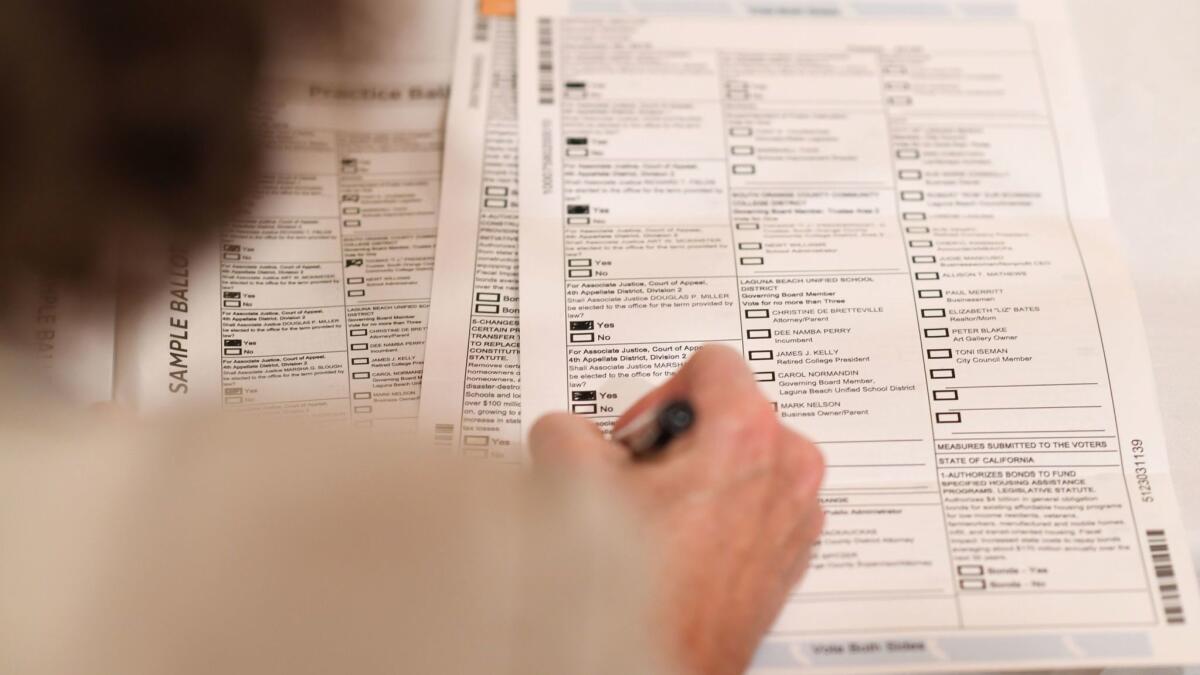

The ballot California voters will tackle on election day is a long one, with dozens of candidates and 11 statewide propositions. While a lot of attention has been devoted to those choices, little has been given to scores of local ballot measures asking for permission to borrow or tax in communities — proposals totaling some $20 billion for schools, cities and counties.

How the local measures ended up on the ballot depends on the community, though all were written by local officials. There are other common threads too — many of these governments have limited options when it comes to funding. State income taxes go to Sacramento; property taxes are constrained by the rules under California’s landmark Proposition 13. And the dollars that do flow from the state and federal governments are often earmarked and off-limits for use on general community needs.

Local dollars are hard to raise at the ballot box. While statewide propositions only need a 50%-plus-1 of the votes cast, some municipal measures need more to succeed. Local bonds require a supermajority vote, with most school construction bonds requiring 55% voter approval. The threshold for taxes, meanwhile, is counterintuitive. Taxes aimed for a narrow purpose or program must win two-thirds of ballots cast. But if it’s for broad government operations, a new tax can be imposed with a simple majority.

That may explain why an overwhelming number of the 254 local tax measures on Tuesday’s ballot are general taxes, according to data compiled by the California Taxpayers Assn. A review of ballot materials in a handful of communities finds that voters are simply told the new tax will help fund basic government operations. But because the single biggest expense for many of these municipalities is public safety, it’s worth taking a closer look at why they might need the money.

The most obvious answer is to pay the salary and retirement obligations local leaders have given to workers through labor negotiations. Pension costs are especially worrisome in a number of communities. This past February, a survey by the League of California Cities found local officials bracing for the effect of new, more conservative state projections of how many pension costs will be covered by investments of the California Public Employees’ Retirement System, or CalPERS.

Set aside the politics and California’s pension math is pretty simple »

As CalPERS lowers those predictions, more of the long-term pension obligation will fall on government employers. The league’s analysis predicted city pension payments will double over the next seven years. The money must come from a local government’s general fund — the beneficiary of any new taxes California voters impose on themselves on Nov. 6.

A review of the proposals shows ideas for new revenue from a variety of sources. In cities such as Milpitas, south of San Francisco, it would be a boost in the hotel occupancy tax. In 73 communities including Chula Vista and Santa Barbara, voters will weigh new taxes on marijuana businesses. In the Riverside County city of Banning, residents will be asked to tax cannabis and to shift a portion of utility taxes to the general fund. Many are likely to pass. A study by the California Local Government Finance Almanac found 74% of these majority-vote, general tax measures for cities have been approved since 2001.

Local leaders carefully craft these tax measures. In some cases, cities hire professional pollsters not only to gauge public opinion, but to test various options for what kind of tax will pass muster with voters. With so few options for long-term sources of revenue to pay for libraries and trash collection — and yes, government worker salaries and benefits — the tax measures could be essential in helping close the gap.

Follow @johnmyers on Twitter, sign up for our daily Essential Politics newsletter and listen to the weekly California Politics Podcast

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.