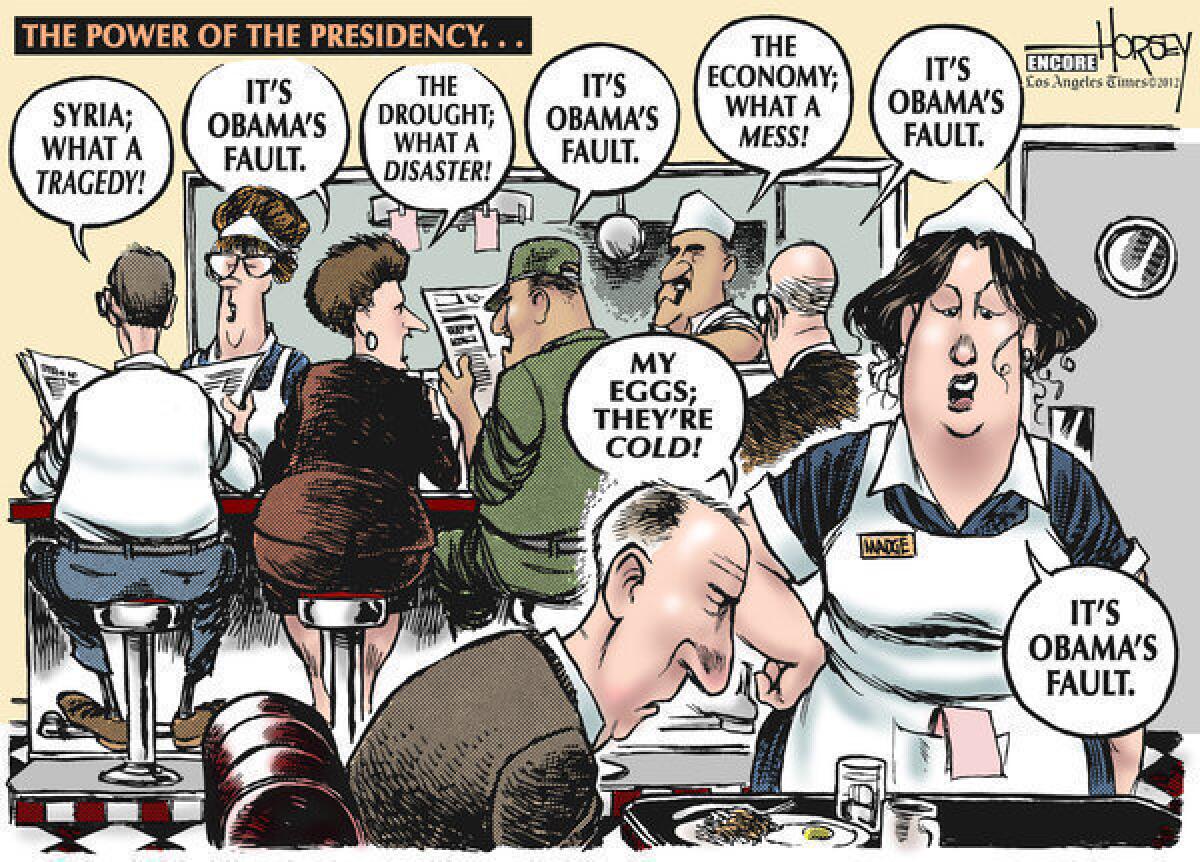

Blaming Obama: Presidential power ain’t what it used to be

- Share via

Presidents get the praise or blame for everything that happens on their watch, but, as Barack Obama has learned, the things the commander in chief can actually command are limited in number, thanks to James Madison and Newt Gingrich.

Madison and his brilliant colleagues who invented the American system of government disagreed about many things, but they fervently agreed about one big thing: the coercive power of government needed to be held in check. They accomplished this by spreading the power around between the executive, legislative and judicial branches of government.

With the advent of the Cold War and the rise of the national-security state, this balance tilted when it came to making war and conducting foreign affairs. In that realm, presidents are now nearly kings. In setting domestic policy, however, presidents still need to make bargains with other power players in order to achieve success. Lyndon Baines Johnson was a genius at getting what he wanted from senators and representatives because, as a senator himself, he had mastered the game. Johnson knew how to reward or coerce every committee chairman, and he knew they could deliver once he bent them his way.

POLITICAL CARTOONS: Horsey’s Top of the Ticket

That is where Newt Gingrich comes in. In 1995, when he became speaker of the House, Gingrich eliminated the long-standing system that had invested most institutional power in the chairmen of the various House committees. Gingrich also brought a more confrontational kind of politics to his caucus that has only become more strident and ideological in the years since he stepped down as speaker.

In the legislative world Gingrich has left us, even a president like LBJ would have a tough time brokering a deal on legislation. Offering the traditional perks or penalties would not have the same effect. Today’s chairmen have neither the absolute power to deliver on a deal nor, in a time when cutting government is their highest goal, do they have the same interest in bringing home the bacon. Most are from safe districts where their most fervent supporters would rather see them confront a president than compromise with him.

There is an interesting article written by Michael Lewis in the October Vanity Fair that sheds light on this new power reality. For several months, Lewis was given extraordinary access to President Obama, and he came away with a insightful portrait of a man who is a bit of a sphinx-like character for many Americans. Perhaps the most revealing passage in the article details how Obama plays basketball -- smartly running a tough, competitive game with players much better than himself. At another point in the Vanity Fair article, though, this very competitive and canny president talks about how difficult it has been to eke out victories in match-ups with members of Congress who no longer play by the old rules:

“[Obama] badly underestimated, for instance, how little it would cost Republicans politically to oppose ideas they had once advocated, merely because Obama supported them. He thought the other side would pay a bigger price for inflicting damage on the country for the sake of defeating a president. But the idea that he might somehow frighten Congress into doing what he wanted was, to him, clearly absurd. ‘All of these forces have created an environment in which the incentives for politicians to cooperate don’t function the way they used to,’ he said. ‘L.B.J. operated in an environment in which, if he got a couple of committee chairmen to agree, he had a deal. Those chairmen didn’t have to worry about a Tea Party challenge. About cable news. That model has progressively shifted for each president. It’s not a fear-versus-a-nice-guy approach that is the choice. The question is: How do you shape public opinion and frame an issue so that it’s hard for the opposition to say no. And these days you don’t do that by saying, “I’m going to withhold an earmark,” or “I’m not going to appoint your brother-in-law to the federal bench.’”

Madison’s vision of checks and balances has served us well, but I wonder what he would think about a government with so many checks on power that prudent balance has given way to partisan gridlock.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.