Does Tom Steyer have real momentum or just a ton of money?

- Share via

HARTSVILLE, S.C. — Rachel Minus is not impressed by the Democratic presidential candidates. They’re just recycling tired talking points for African American voters like her, she said — with one curious exception.

The South Carolina millennial is all in for Tom Steyer, a Bay Area billionaire who’s been caricatured by critics as the definition of a rich, entitled white guy.

“I get the feeling he cares about us,” Minus said, as she waited for Steyer to take the stage here at the Jerusalem Baptist Church, a black congregation dating to the late 1800s. “The other candidates say things that are lip service. We have seen it year after year with the Democratic Party. So when they keep repeating the same talking points, you listen to it and it falls on deaf ears. He’s genuine.”

That sentiment is especially significant in a state where about 3 in 5 Democratic voters in the presidential primary four years ago were African Americans. Steyer’s aggressive spending here and in Nevada bought enough support in state polls to allow the former hedge-fund manager to qualify for last week’s nationally televised Democratic debate, much to the annoyance of some rivals and a chorus on social media.

As a campaigner, his personal politicking is uneven and he is prone to rambling. His one viral moment came when Steyer was caught on camera post-debate, awkwardly trying to greet rivals Bernie Sanders, the Vermont senator, and Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren even as the two were in the middle of a heated, private exchange.

“You got caught in the crossfire!” Congresswoman Alma Adams joked at a news conference Saturday morning next door in Charlotte, N.C. (The event was about Steyer’s plan for investment in historically black colleges and universities, but the two never got around to talking about the endorsement or the policy details.)

Steyer knows something about organizing in minority communities. In the years before running for president, he built a national advocacy machine that galvanized community activists, registered young voters and persuaded Californians to raise billions in taxes — all to advance the causes of social justice, action against climate change and affordable healthcare.

Although Washington insiders generally dismiss his recent momentum as likely to be short-lived, some of this area’s political denizens aren’t so sure.

“People are saying, ‘This guy, maybe we ought to look at him,’” said Bruce Ransom, a political science professor at Clemson University. “Is it enough to prevail in February? Doubtful. But if the candidates come into the election here all bunched up and he has an established foothold, then who knows?”

A recent Fox News poll showed that Steyer has moved into second place in South Carolina, with 15% support among likely Democratic primary voters. While that’s 21 percentage points behind former Vice President Joe Biden, Steyer is running a “high-tech, high-touch” campaign, said Antjuan Seawright, a South Carolina political strategist unaffiliated in the race. “He’s got some soldiers on the field who know how to do war in South Carolina.”

Ninety percent of the campaign’s nearly 100 organizers are from South Carolina. They are in all of the state’s 46 counties, and more than half are organizing neighborhoods within 10 miles of where they were born. “Instead of bringing in folks from other states who need to learn the lay of land, our team is literally organizing their friends, their family and their neighbors,” said Brandon Upson, Steyer’s national organizing director.

Columbia Mayor Steve Benjamin, a national co-chair of rival Michael R. Bloomberg’s campaign, said he’s received more mail from Steyer than all the other candidates combined. (Bloomberg made a strategic decision to not compete in South Carolina, focusing his campaign instead on bigger states that vote later.)

At events in both North and South Carolina over the weekend, Steyer told diverse crowds that the media has gotten him all wrong. “I know that when I’m described in the press, I’m often described as a rich person or a billionaire,” Steyer told black leaders in Charlotte. “I think I’m a different person from that two-dimensional stereotype.”

He talked of his mother’s work as a tutor in a Brooklyn detention center. He stressed the community bank in Oakland that he ran with wife Kat Taylor, who puzzled some attendees at Steyer’s events by abruptly bursting into song, sometimes Billy Joel’s “Summer, Highland Falls,” when she introduced him. At every stop, he talked of the urgency of reparations for descendants of enslaved people. Steyer is not the only candidate emphasizing issues of race but he is doing so most persistently in South Carolina.

The anger Steyer seems to instill among President Trump’s supporters in inland South Carolina so intrigued Democrat Paula Wise, an African American insurance company employee, that she came to see him over the weekend. “It tells me this is somebody I really need to look at,” she quipped.

Not one of the many Democratic voters interviewed in the state were troubled by Steyer’s use of his deep bank account to gain traction.

“It is like a knife,” said Shalon Jordan, 40, a tax preparer in Hartsville. “You can use the knife to hurt somebody. Or you can make a great meal. If he is going to make a great meal with his billions, then that is a good thing.”

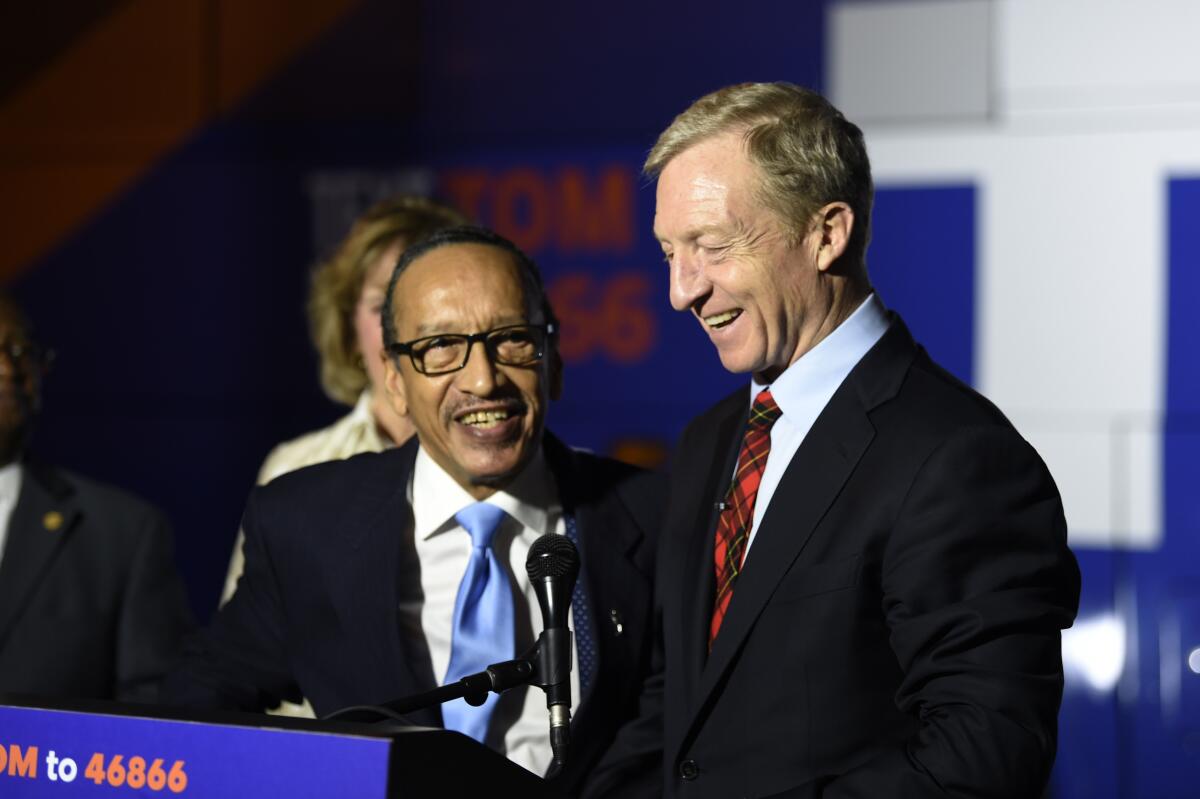

Supporters talk openly about the transactional nature of politics. As Johnnie Cordero, the head of the Democratic Black Caucus of South Carolina, announced his endorsement in Florence, he praised the hiring Steyer has done — from the Democratic Black Caucus of South Carolina.

“Part of what makes you a serious candidate for African Americans in South Carolina is the fact that you put your money where your mouth is,” Cordero said. “Why is it alright for a billionaire donor to support the Democratic Party, but that same billionaire donor cannot put his money where his mouth is and support a campaign for himself?”

Steyer raised the topic of his hedge-fund fortune only to press his case that he, as a financial titan, can best call out Trump as a fraud. And he distinguished himself from the other billionaire in the race, former New York Mayor Bloomberg.

“We have totally different backgrounds and experiences,” Steyer said as his campaign bus rolled through rural South Carolina. “If someone as rich as Bloomberg wants to represent Democrats … he especially needs to embrace a wealth tax.” Bloomberg, whose fortune dwarfs that of Steyer, says rich people should pay higher taxes, but he has pilloried wealth-tax proposals as Venezuelan-style socialism.

Both Steyer and Bloomberg emphasize the “climate emergency” more than other candidates. After a spate of natural disasters in the South, the issue seems to be catching on for Steyer. “Four years ago that may not have resonated here,” said Benjamin, the Columbia mayor. “Now it resonates a lot. We have seen several years of what were supposed to be ‘once in a lifetime’ events.”

Steyer is betting that his money will enable him to outlast Biden, who enjoys the most support among African American voters of any Democratic candidate, and that a weak showing by the former vice president in Iowa or New Hampshire, the first states to vote, will weaken Biden’s base of support in the South.

It’s a long-shot gamble, but Steyer takes encouragement from voters like Wes Simmons, a 64-year-old business consultant who was among the roughly 200 people in Charlotte who came to hear him Friday night.

“Biden is showing his age,” Simmons said. “He is not as sharp, not as quick. And Trump is a mean-spirited campaigner. There are folks wondering, what is the alternative? What else is out there?”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.