As Trump attacks Biden on China, he’s playing a weak hand

- Share via

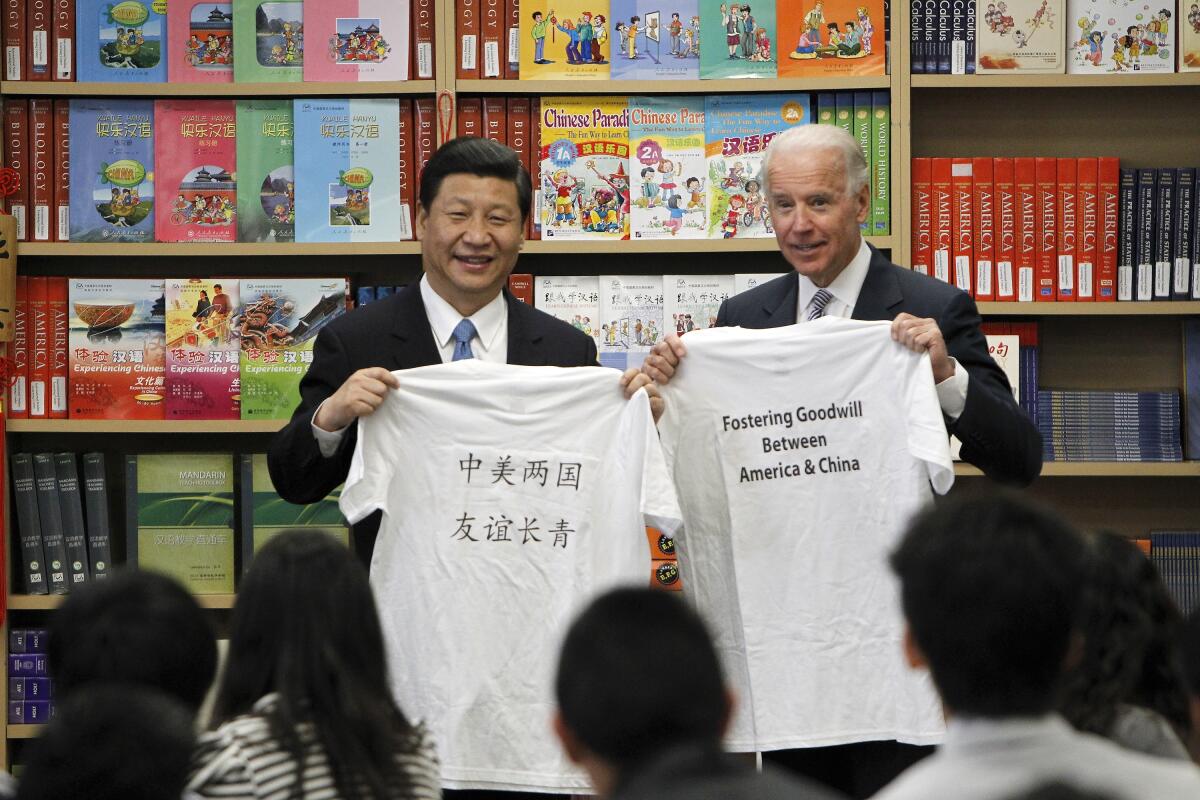

WASHINGTON — As vice president, Joe Biden chummed around with China’s Xi Jinping from South Gate to Beijing, boasted of tutoring him on American politics during long walks and quiet dinners, and even helped him forge partnerships with Hollywood movie moguls.

President Trump subsequently worked just as hard to charm the Chinese autocrat, guiding him on a tour through Trump’s gilded Florida resort, posing for a joint portrait in Beijing’s ancient Forbidden City and repeatedly praising his “friend” for controlling the coronavirus outbreak.

For Xi, such coziness with U.S. leaders was invaluable as he consolidated power at home and argued for China’s preeminence on the world stage. Those same moments have become toxic for both Biden and Trump, however, as they contend for the presidency with U.S.-China relations as bitter as at any time in memory and Xi the symbol of America’s failed policies from trade to pandemic control.

For all of Trump’s own chumminess with Xi, his campaign sees voters’ anti-China sentiment as one of his most potent weapons against Biden, echoing a strategy Trump used in 2016 to portray Hillary Clinton as a globalist more eager to rebuild the U.S.-China relationship than to protect American manufacturing and tech jobs. Yet that isn’t proving an effective cudgel for Trump this go-round — not after 3 ½ years of his own missteps with China.

“We’ve squandered credibility, but with very little strategic gain,” said Jude Blanchette, a China expert at the nonpartisan Center for Strategic and International Studies, in assessing U.S. policy over the Trump years. “We’ve done nothing to dent China’s view of the world or change its strategy.”

During Trump’s presidency, China has furthered its incursion into the disputed South China Sea, given little in trade deals despite U.S. tariffs that have boomeranged on American farmers, cracked down on democracy activists in Hong Kong and put religious minorities in concentration camps in Xinjiang, all with little resistance.

Last week marked the end of U.S.-China engagement. The two powers may now be sliding toward a severance of relations and even outright military conflict.

As U.S. influence ebbed and warring administration factions clashed, Trump has vacillated between hurling racial slurs — blaming China both for the coronavirus’ spread and for the resulting American job losses — and continuing to flatter Xi as Trump grasps for a more favorable trade deal.

Multiple polls show Trump no longer holds an advantage on the question of which candidate Americans believe would better handle China. And the enthusiasm some top Chinese Communist Party officials express for Trump’s reelection — believing the U.S. is an ever-weaker adversary with him in the White House — is a damning endorsement for a leader trying to present himself as a bulwark against an ascendant rival superpower.

With all this baggage, another politician might avoid the China topic. Not Trump.

Even the recent, embarrassing revelations by one of Trump’s former national security advisors, John Bolton, that the president sought help from China toward his reelection have not deterred a strategy of trying to brand the former vice president as “Beijing Biden.”

The president and his team believe Biden will pay a heavy political price for the sharp turn in public opinion against China, so long as they keep the attacks coming.

Three medium-size moving trucks have left a U.S. Consulate in southwest China as its impending closure drew a steady stream of onlookers.

Trump renewed his assault recently in a meandering Rose Garden polemic that blamed Biden for all the challenges the Trump administration has encountered with China, including its crackdown on Hong Kong. (Bolton, in his tell-all book, wrote of Trump’s assurances to China that he saw Hong Kong’s governance as “a domestic Chinese issue,” in keeping with Trump’s pattern of ambivalence toward international human rights.)

Biden does have his own record on China to answer for, not only as vice president but also, before that, as a senator deeply involved in foreign policy. Were he facing an opponent more effective than Trump, and less culpable, Biden might be in a tough spot. He was central to an Obama-era policy that even administration alumni now acknowledge was too patient, too often defaulting to conciliation over confrontation.

Ely Ratner, a former Biden advisor now at the Center for a New American Security, co-wrote in Foreign Affairs in 2018, “Nearly half a century since Nixon’s first steps toward rapprochement, the record is increasingly clear that Washington once again put too much faith in its power to shape China’s trajectory.”

“The Obama administration was a little slow in realizing how assertive Chinese foreign policy was going to be and the extent to which China was going to crack down domestically,” said Bonnie Glaser, director of the China Power Project at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Biden’s dealings with China date to at least 1979, when as a senator he joined an American delegation to meet the new leader, Deng Xiaoping, during a period when China and its economy remained largely cut off from the West. During the Obama years, he spent endless hours cultivating Xi, who early on was China’s vice president and heir apparent. President Obama’s team sensed that China would continue moving toward democracy and capitalism when Xi ascended to the presidency.

Moves by Britain, India and Australia signal an emerging if loose coalition against Beijing’s expansionism, economic warfare and COVID-19 propaganda.

Critics’ warnings that the United States was misreading Xi, and risked getting played, proved prescient not long after Xi became president in 2013.

China quickly reneged on assurances Biden helped extract from Xi that Beijing would cease its military aggression in the South China Sea. The disputed waters, valuable for shipping lanes and natural resources, are considered vital to American allies in the region. Human rights abuses escalated inside China. And a deal Biden brokered to curb Chinese government-sponsored cybertheft ultimately unraveled.

On Wednesday, such cybertheft drove the Trump administration to order the closure of the Chinese Consulate in Houston, an extraordinary escalation in the tension between the U.S. and China. Beijing retaliated on Friday, ordering the U.S. Consulate in Chengdu closed.

Stephen K. Bannon, an informal advisor to Trump and the leading architect of his populist 2016 campaign, called confronting China “the single strongest issue” for Trump and “a huge vulnerability” for Biden.

Bannon, in an interview, called Biden “a useful idiot” to the Chinese Communist Party. He predicted that Biden’s tough posture on China of late will not make white working-class voters forget what Bannon characterized as a record of appeasement: “He’s going to have to defend that in the Upper Midwest.”

Yet it is Trump who is losing ground with those voters, even as his campaign spends big on advertisements that target Biden’s China record and the president and his allies raise the issue at every opportunity.

Biden “cannot undo what he has done in the past by lying to the American worker,” Donald Trump Jr. said in a recent call with dozens of reporters. Republicans are spotlighting past Biden remarks that sound tone-deaf now, including one last year when Biden mocked rivals warning about China’s economic threat and said its leaders are “not bad folks” and “they’re not competition for us.”

Biden supporters are increasingly confident that the voters who in 2016 rebelled against establishment Democrats like him are coming back as they see the results of frayed international alliances, isolationist trade policies and inattention to human rights. Biden attributes the United States’ inept response to COVID-19 in part to Trump’s failure to work with other nations, including China when necessary.

Biden-style diplomacy, Democrats argue, enabled the U.S. to exert international pressure on China that proved effective in confronting its human rights abuses and forcing cooperation in areas where it was in the American interest. They cite Xi’s support of the Paris agreement on climate change, the Iran nuclear deal and international efforts to isolate North Korea until it forfeits its nuclear weapons. Trump has renounced all three of those policies.

Get our L.A. Times Politics newsletter

The latest news, analysis and insights from our politics team.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

The Obama administration’s main effort to counter Chinese economic influence, the 12-nation Trans-Pacific Partnership trade pact, fizzled after Trump withdrew the United States from it during his first month in office. While the other Pacific Rim nations held to the agreement, it was a far less effective counterweight without America’s economic heft.

“Biden’s underlying policy has really been, it’s better to talk than not talk,” said David M. Lampton, a China scholar at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies. “And don’t make threats you can’t deliver on.”

Biden does point to his role in incremental achievements in China to bolster his claim to be a steady hand who can bring allies together to build U.S. influence.

Midway through the Obama administration, he was in China when it announced a “military defense zone” in the airspace of U.S. allies in Asia, declaring planes could not fly through it without Chinese permission. “He pushed back in a way that caused the Chinese to cease and desist its efforts to try to enforce it,” said Daniel Russel, Obama’s assistant secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific affairs, who was traveling with Biden at the time. “He made it clear that we were going to keep flying through the area and that Japan and South Korea were 100% with us.”

On an earlier trip, Biden jousted with the Chinese premier, who taunted the American delegation about a credit downgrade of U.S. Treasury bonds and warned that China expected its large bond holdings would be repaid. Go ahead and liquidate them, Biden countered — China owned a small fraction of U.S. debt and wouldn’t find a better investment elsewhere.

Biden has spent little time defending his own record, however, trying instead to link Trump’s poor record on the pandemic response to his overall dealings with China.

He’s attacked Trump’s move, before the virus hit the United States, to hollow out a U.S. disease-response team that had been in China, and the president’s erratic comments as the virus spread. Trump alternated between praising Xi for controlling it — a tactic Trump believed would help win trade concessions — and blaming China for spawning a “plague,” the “kung flu” or “the China virus,” slurs that have hindered cooperation that many disease experts say is crucial to investigating the pathogen.

The Bolton book, released in June, proved an unexpected boon for the Biden campaign. Bolton reported that Trump consistently pushed his own political interests over the national interest in negotiating with China, including “pleading with Xi to ensure he’d win” election by boosting purchases of American soybeans and wheat. And, Bolton wrote, Trump told Xi he “should go ahead with building the camps” that detain more than a million Uighurs, a Muslim ethnic minority, in Xinjiang, calling it “exactly the right thing to do.”

The administration disputes the account. But when it comes to the candidates’ battling about China, the revelations in Bolton’s book seem to be taking a bigger political toll on Trump than Trump’s attacks on “Beijing Biden.”

By early July, a couple of weeks after Bolton’s book began circulating, a Suffolk University/USA Today poll asked voters whom they trust more to deal with China. It was no longer a toss-up, as in earlier polls: Biden was favored by 10 percentage points.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.