America wakes up to politics: 2020 brings a tsunami of voting and activism

- Share via

WASHINGTON — The American electorate, often apathetic and cynical about politics, is experiencing a great awakening, with the 2020 election inspiring extraordinary levels of engagement in both parties.

People are enduring hours-long lines to cast ballots, early voting is shattering records, and turnout may be the biggest in more than a century. Millions who did not vote four years ago — or ever — are showing up.

Campaigns can’t keep up with the demand for yard signs. Progressive groups have proliferated and been deluged with volunteers. Small-dollar donations have skyrocketed. The Trump campaign claims more volunteers than the grass-roots army of Barack Obama, whose 2008 election marked the previous high point for voter enthusiasm.

The last four years have demonstrated even to the most addled voter that who is in the White House really does make a difference. Whatever else the consequences of his presidency are, President Trump — love him or loathe him — has catalyzed a surge of political engagement. The intense polarization of the Trump era has strained Americans’ ability to live peaceably with their neighbors, but it’s also spurred people to participate as never before.

“People will walk over broken glass to vote for the president,” said Matt Batzel, the Wisconsin-based executive director of American Majority Action, a conservative group, who said passions were running as high in Wisconsin as during the tumultuous 2012 campaign to recall then-Gov. Scott Walker, a Republican.

“People are digging deep because they see this as an existential threat,” said Ethan Todras-Whitehill, co-founder of Swing Left, an online portal for people seeking to give donations and volunteer time for progressive candidates that was started after Trump was elected.

Americans are still less likely to vote than in many other countries, and registration drives this year were hampered by the pandemic. But there have been bright spots: In Travis County in Texas, 97% of eligible voters registered this year.

Those who are registered are making a mockery of predictions that turnout would suffer because of the pandemic. It could be the highest since 1908, when ballots were cast by 65.7% of eligible voters (a much smaller population in the era before women won the right to vote).

“People are very much engaged in this election,” said Michael McDonald, a University of Florida professor who tracks voting at the nonpartisan U.S. Elections Project, which reports that, as of Sunday, 59 million ballots had already been cast.

That is more than 43% of the 137 million who voted in the 2016 general election; and according to an Associated Press analysis, it is already — with more than a week before election day — more than the total number of early ballots cast in 2016. In Texas, the early vote is coming in so fast, it has already hit 80% of the state’s 2016 vote total. In California, almost 45% of the 2016 total has come in.

Paradoxically, the pandemic may have spurred rather than inhibited voting.

“You put those unprecedented levels of interest and enthusiasm together with raising the stakes in a global pandemic and making voting more accessible, you end up with turnout at breathtaking levels,” said Tom Bonier, chief executive of TargetSmart, a Democratic vote-analysis firm.

The stamina of early voters is as striking as their number. In Georgia, some waited at polling stations for as long as 11 hours. In Florida, where more than 300,000 cast ballots on the first day of in-person voting, many waited in long lines in the rain.

“What it says is not just they are voting early out of fear of a repeat of 2016, but also out of determination,” said John Anzalone, a pollster for Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden. For these voters, “you not only know what is at stake in this election, but you want to make sure your vote counts.”

Although many early voters are regulars, a lot are new: TargetSmart estimates that a quarter of the early vote nationwide has come from people who did not vote in 2016.

According to Gallup, 67% of Americans say they are more enthusiastic than usual about voting — more than the firm has ever recorded. Other polls emphasize how much Trump drives that enthusiasm on both sides — Republicans voting more out of support for him than hostility to his rival, while Biden supporters see their votes as more anti-Trump.

Voting isn’t the only thing at record levels:

Amid fears about a shortage of poll workers because the pandemic has sidelined older people who typically help, a stampede of volunteers has come forward in many places. In Madison, Wis., so many people signed up to work the polls — twice as many as in the previous three presidential elections — officials shut down the application process.

Political contributions have soared, and the number of small donations has shot through the roof. The nonpartisan Center for Responsive Politics said in an Oct.1 report that small donors — people giving $200 or less — made up 22% of all federal committees’ fundraising, up from 14% in 2016.

ActBlue, the online fundraising platform for Democrats and progressive groups, made headlines in January when it announced it had brought in $1 billion from small donors in 2019. That seems paltry now: The group raised $1.5 billion in just three months this year, from 6.8 million donors, federal filings for the July-through-September quarter show.

As of Sept. 30, Biden had raised about 32% of his money, $259 million, from small donors. Trump raised half his money — $272 million — from small donations, more than any presidential candidate in history, according to the Center for Responsive Politics.

Grass-roots activism is on fire on both sides, drawing both seasoned campaign veterans and newcomers such as Melanie Blair of Lebanon, Ohio. An insurance agent who had never campaigned before, Blair, 54, now shows up to wave Trump flags on street corners. Infuriated after her Trump lawn signs were stolen, she built an oversize wooden sign to make it harder to cart off.

“I’m worried about the future of my children,” Blair said about her decision to get involved. “I see it as a choice between freedom and socialism.”

Her sister, Lori Viars, a longtime Republican activist in Ohio, said conservatives were more enthusiastic about Trump than in 2016.

“We were voting against Hillary [Clinton] more than voting for Trump,” Viars said. “But now that President Trump has done such a great job and kept his campaign promises, we are excited to support him for reelection.”

Since Sen. Kamala Harris launched a bid for the Democratic presidential nomination, the problems of the country she wants to help lead have inched closer to her Brentwood doorstep.

In Maine, Louise Savage, a Republican from Sidney, also sees more enthusiasm for Trump than four years ago. Savage said that when she dressed up for her workplace’s “Super Hero Day” in Trump regalia, she was swamped with requests for signs and buttons.

Among Democrats, many have been mobilized for the first time through grass-roots resistance groups that popped up after Trump’s election, such as Indivisible, a network of local progressive activists. The group started with 6,000 chapters, and says it has grown to more than 1 million members.

Swing Left estimates that 40% of its volunteers are coming to politics for the first time.

Vote Forward, backed by a coalition of liberal groups, offered a pandemic-friendly way for Democrats to channel anti-Trump energy: writing, by hand, get-out-the-vote letters to people in battleground states and districts. Some 200,000 people stepped up, and more than 17 million letters were dropped in the mail at once in early October.

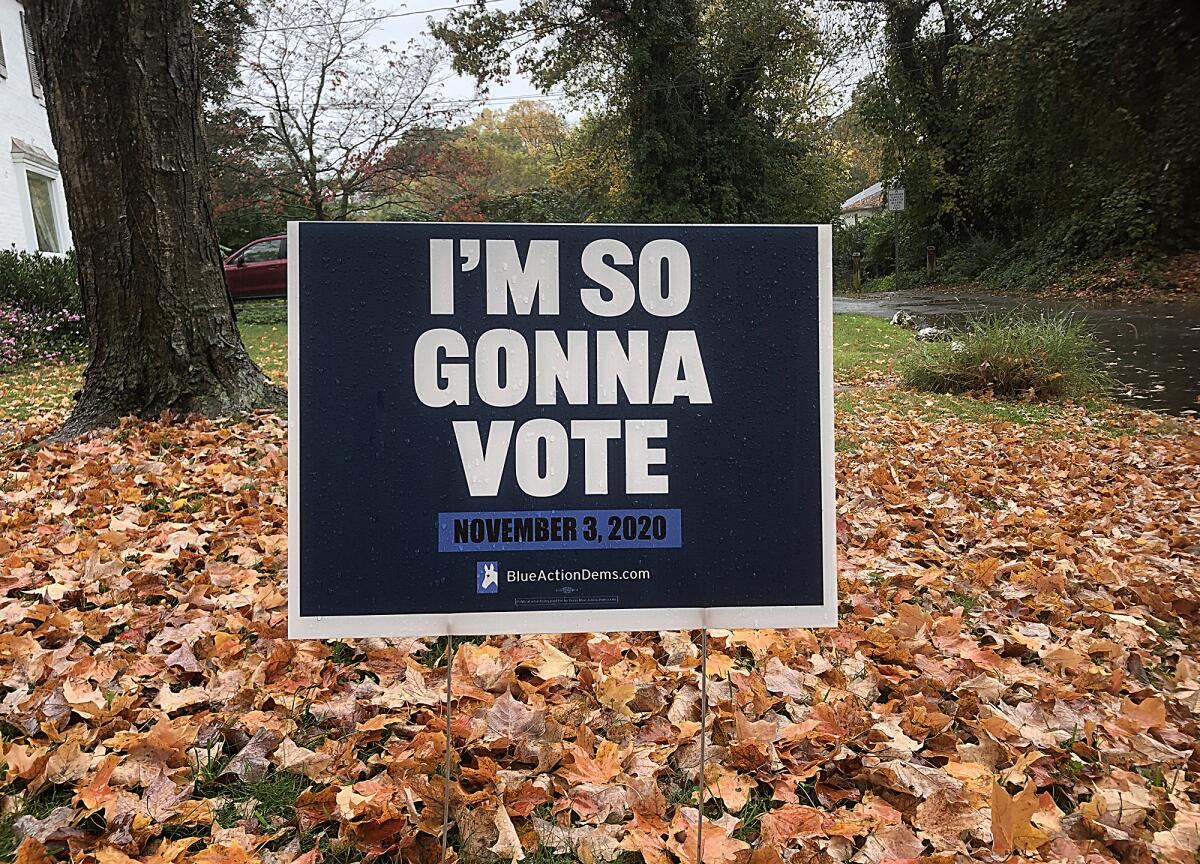

Yard signs, which many campaigns had started to abandon before Trump, have become particularly popular on both sides in the midst of the pandemic.

“I’ve been doing yard signs for 15 years, and I have never seen as much excitement,” said Jane Kleeb, chair of the Nebraska Democratic Party. When the party arranged a drive-through yard sign distribution, cars lined up for a mile before the event started.

The Bangor office of the Maine GOP found its supply of yard signs so depleted, it had to import some from New Hampshire.

Some simply show enthusiasm for voting. “I’m so gonna vote,” says one sign distributed by progressives.

A key question is whether 2020’s sharp rise in voter engagement is a fleeting product of a presidency that inspires passion on both sides or the beginning of a lasting change.

“If Trump loses and leaves the political scene, we could see a return to normal and people will be less engaged,” said McDonald, the voting turnout expert. “But we know that voting is habit forming. Once you vote, you are much more likely to vote again.”

Black voter turnout surged for Obama’s two elections, he noted, then it receded — but to levels higher than before Obama ran.

For some, Trump’s election has been a life-changing event, and there is no going back to a life of passive citizenry.

Joy Davis, a former accounting assistant in the oil and gas industry in Houston, became politically active for the first time in the 2018 midterm election campaign, working with the progressive group MoveOn.org.

Now she is canvassing, voted early for Biden and has no plans to quit politics after the election.

“After Trump was elected, I was looking for ways to plug in,” said Davis, a 44-year-old Black voter. “Whether Trump wins or loses, we’re going to be looking at how the criminal justice system can be improved for Black and brown people.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.