- Share via

WASHINGTON — Florida is a “refuge of sanity” and a place where “woke goes to die,” Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis said after winning reelection earlier this month. California is a “true freedom state” that rejects “demonization coming from the other side,” Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom promised.

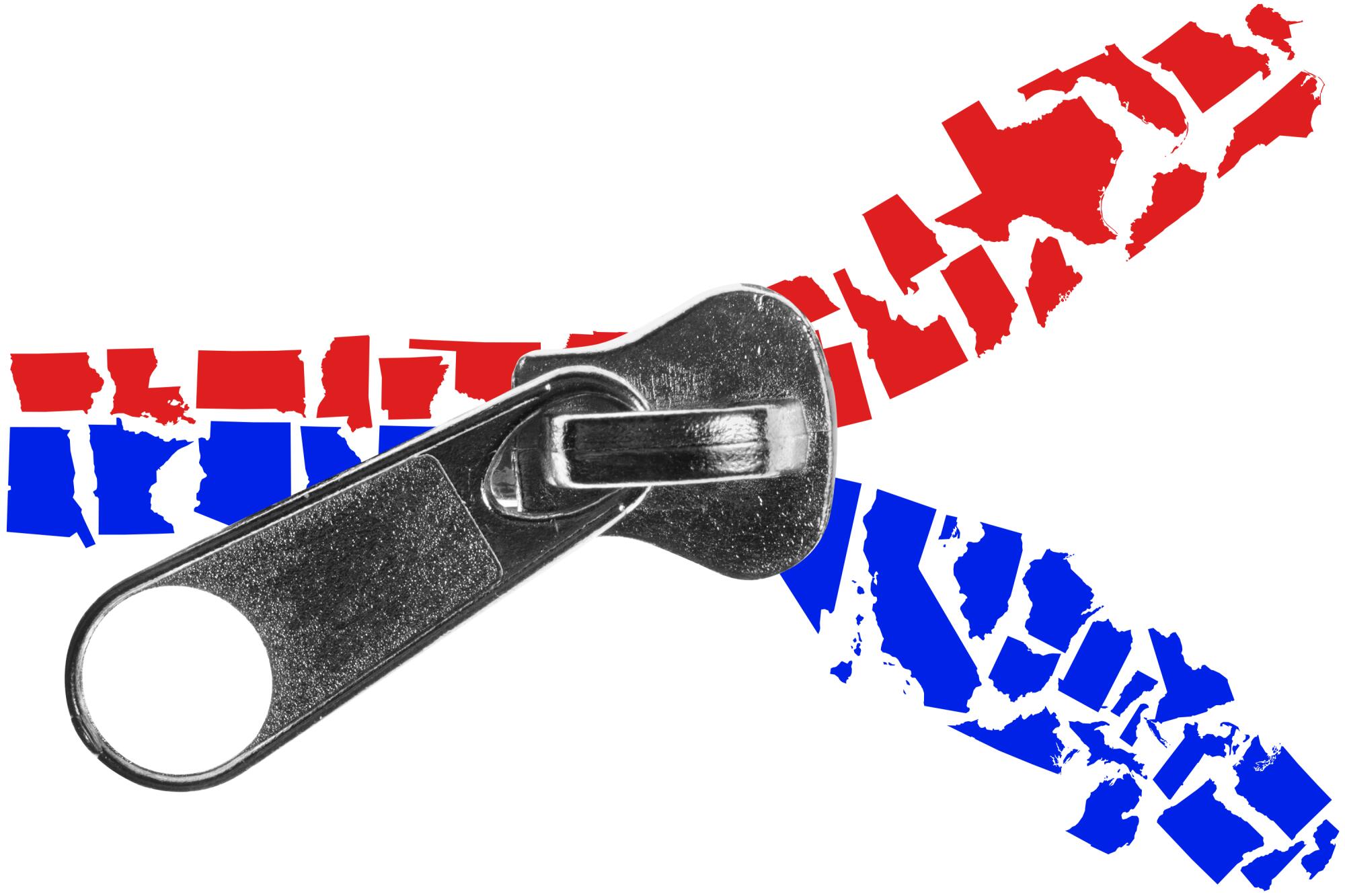

The two governors’ declarations of independence are only the latest signs that the next two years’ fiercest political battles will be fought not in Washington, but among clashing states.

Divided government is returning to the nation’s capital. President Biden, who turns 80 on Sunday and is suffering from low polling numbers amid high inflation, is seen as vulnerable by members of both parties, giving him less leverage to find common ground with Republicans, who will control the House of Representatives.

But come January, more than 80% of Americans will live in states with governments entirely controlled by one of the two major parties. After new legislators and governors are sworn in, the governorship and both chambers of the legislature will be controlled by the same party in at least 39 states, a seven-decade high.

As a result, Americans will see even more differences in their schools, workplaces and doctors’ offices when they cross state lines.

“We’ve got Texas going, ‘We’re going to do our own thing,’ run by a conservative governor, and you’ve got in California a liberal governor wanting to do their own thing,” Pat McCrory, former GOP governor of North Carolina, said in an interview.

Citizens’ rights to carry a gun, get an abortion or join a union and their rate for a minimum wage job now depend almost entirely on whether their state is blue or red. Biology and American history texts offer different curricula on slavery, Jim Crow and human sexuality.

Few areas — large or small — are left undivided. California and New York, another blue state, passed job rules this year to foster pay equity, joining Colorado in requiring employers to disclose more about salaries. Texas, Florida and other red states passed laws against gender-affirming care for children — protected in many blue states — while imposing rules intended to keep transgender girls out of youth sports.

As a conservative Supreme Court grants states more leeway to make their own rules on abortion and voting rights, those combustible issues are in play as well.

States’ attorneys general and legislators have joined governors in the national fray, hoping to gin up their fundraising and expand their online fan bases.

Since Biden took office in January 2021, Republican attorneys general have filed 50 lawsuits against his administration over a host of issues, including California’s fuel standards, financial industry regulations and protections for LGBTQ students.

In the four years former President Trump was in office, Democratic attorneys general sued him 155 times over such issues as his travel ban on people from Muslim countries and his decision to end legal protection for people who arrived in the country illegally as children.

Multistate litigation against the federal government — once rare — has increased dramatically since the Obama administration, which was sued 58 times by Republican attorneys general over the course of two terms, according to Paul Nolette, a Marquette University political scientist who tracks such lawsuits.

At the same time, state governments are enacting bolder legislation, often taking on issues such as immigration and climate treaties that were once the exclusive purview of the federal government.

California’s climate agenda mixes the symbolic with the substantive. In June, Newsom signed a climate pact with Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau during the Summit of the Americas conference in Los Angeles.

Newsom has also signed laws casting California as a “sanctuary state” from red states that restrict access to abortion and gender-affirming care for trans children.

The partisan clashes between red- and blue-state governors and the widening gaps between the experience of living in a red state and a blue state are dividing the country more distinctly into two societies.

In the last 80 years, the policy and partisan chasm between liberal and conservative states has grown wider than ever, according to Christopher Warshaw, co-author of a new book called “Dynamic Democracy: Public Opinion, Elections, and Policymaking in the American States.”

Since the civil rights era, all states have moved to the left, with some exceptions, including on gun and abortion rights. But in the past, you might have had a few more liberal policies in a conservative state like Idaho, and a few conservative policies in a liberal state like Maryland, Warshaw said.

“Today, the liberal states have mostly liberal policies and conservative states have mostly conservative policies,” he said. “Lots of things that affect people’s everyday lives are quite different.”

Some conservatives applaud the trend toward a less centralized country.

“It’s important for our country that Washington be functional,” said Arkansas Gov. Asa Hutchinson, a Republican who will finish his term in January and is considering a run for president. “But in the absence of that, the governors are always addressing these issues as well.”

Hutchinson concedes that some problems have to be tackled by the federal government. He noted that Republican governors like him have given tax breaks and that Democrats have offered rebates intended to combat inflation.

Both methods offer relief, he said, but don’t “get to the core problem.”

Even some fellow Republicans cringed when DeSantis flew migrants from Texas to Martha’s Vineyard, Mass., in September with false promises that they would find jobs in Boston.

“Regretfully, I think you’ll continue to see some of the flashiness that, you know, captures national attention,” Hutchinson said when asked about the flights

and Newsom’s sanctuary state declarations. “There’s a balance there between sending important messages to Washington that something needs to be done, [and] simply trying to grab a headline.”

The fight to seize issues can get confusing for voters, as they watch national figures campaign on traditionally local issues such as crime and education and local figures campaign on national issues such as immigration.

Engaging in national politics is a way for state and local politicians “to distract from the things they’re responsible for,” said McCrory, the former North Carolina governor, who was in officer during a battle over transgender rights that prompted California to ban spending state money on travel to states with anti-LGBTQ laws. “It’s a common pivot for politicians.”

Liberals have been slow to respond to conservatives’ long-term strategies on issues such as abortion at the state level, where the GOP has chipped away at rights for decades while building a Supreme Court majority that would give states more power to restrict them further, said Meaghan Winter, the author of “All Politics Is Local: Why Progressives Must Fight for the States.”

“Democrats and people on the left, and even centrists, from my perspective, don’t take seriously that we live in a federalist system, because they ideologically don’t agree” with the concept, she said.

The result, she said, has been widened inequity.

Conservative policymakers are often more responsive to national Republican politics than to local concerns, said Jamila Michener, author of the book “Fragmented Democracy: Medicaid, Federalism, and Unequal Politics.” For example, after Democrats expanded Medicaid — the health insurance program for poor people, pregnant women and people with disabilities — to cover more people, some conservative states refused to expand it, even though the federal government would cover the majority of the cost.

Now rural hospitals across the South are closing because state lawmakers have rejected the federal funding that could save them, Michener noted.

Corporations and well-funded interest groups have more money and clout to fight policy debates in 50 different states, she said, than do vulnerable people and the groups that represent them.

Some evidence suggests voters still prefer moderation — when they can get it. Govs. Charlie Baker of Massachusetts and Larry Hogan of Maryland, both Republicans leading blue states, have topped lists of the nation’s most popular governors.

“A Republican running in a more liberal state and governing in a liberal state, you have no choice but to moderate your viewpoints and get something done,” said Baker’s chief of staff, Tim Buckley, repeating Baker’s mantra.

That may be true, but both Baker and Hogan are leaving office in January, and will be replaced by Democrats who easily defeated Trump-backed Republicans.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.