High radiation levels found in giant clams near U.S. nuclear dump in Marshall Islands

- Share via

Reporting from Majuro, Marshall Islands — Researchers have found high levels of radiation in giant clams near the Central Pacific site where the United States entombed waste from nuclear testing almost four decades ago, raising concerns the contamination is spreading from the dump site’s tainted groundwater into the ocean and the food chain.

The findings from the Marshall Islands suggest that radiation is either leaking from the waste site — which U.S. officials reject — or that authorities did not adequately clean up radiation left behind from past weapons testing, as some in the Marshall Islands claim.

The radioactive shellfish were found near Runit Dome — a concrete-capped waste site known by locals as “The Tomb” — according to a presentation made by a U.S. Department of Energy scientist this month in Majuro, the island nation’s capital. The clams are a popular delicacy in the Marshall Islands and in other nations, including China, which has aggressively harvested them from vast swaths of the Pacific.

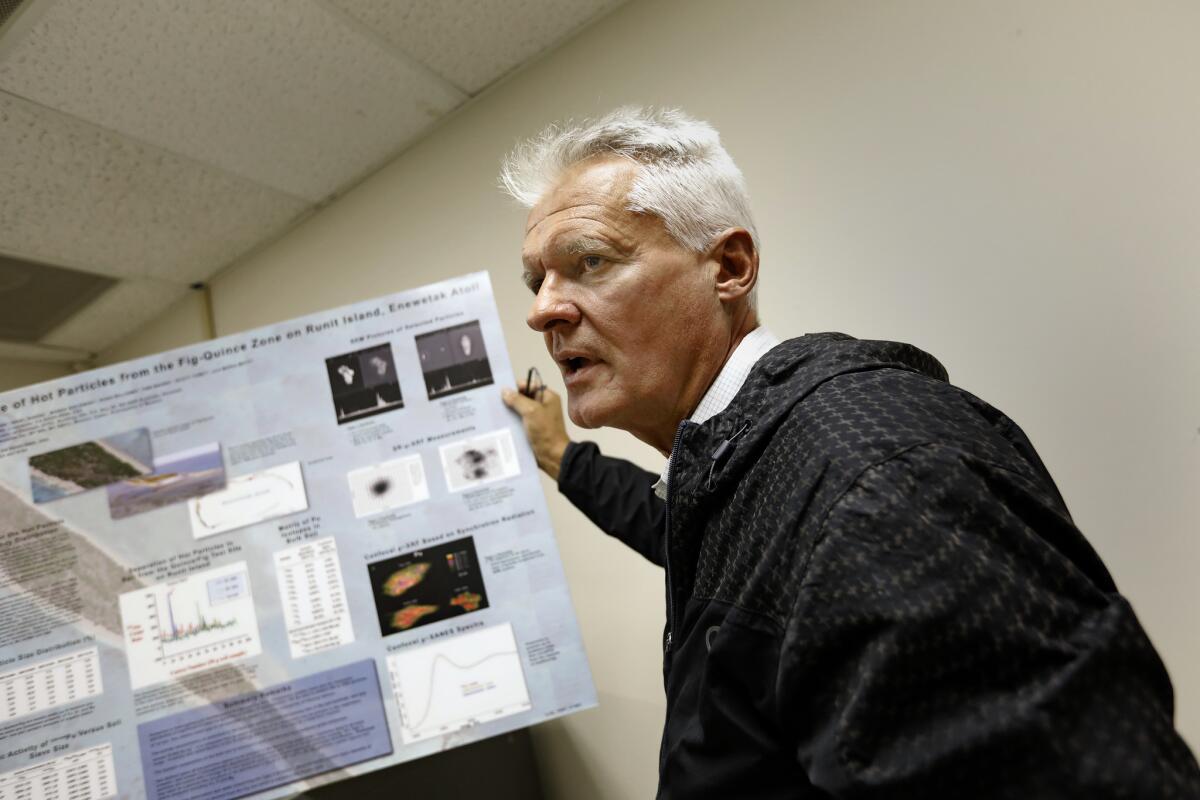

According to Terry Hamilton, a veteran nuclear physicist at the Energy Department’s Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, Runit Dome is vulnerable to leakage by storm surge and sea level rise, and its groundwater, which is leaking into the lagoon and ocean, is severely contaminated.

But the radiation in the shellfish and surrounding lagoon is not coming from the 40-year-old dome, said Hamilton in a slide he presented May 15 to an audience assembled in a hotel conference room in Majuro.

He said isotopic analyses indicated the lagoon contamination was from residue from the initial nuclear weapons testing.

The Los Angeles Times was not at Hamilton’s presentation, and the Energy Department did not make him available to comment. But the following day, residents and officials informed The Times about the findings, which were later confirmed with others.

Between 1946 and 1958, the United States tested 67 nuclear devices in the Marshall Islands, including 44 in Enewetak Atoll, one of the nation’s 29 coral atolls. Although the Marshall Islands were home to only 6% of the total number of tests conducted by the United States, it bore the brunt of more than half the total energy yield of all U.S. nuclear weapons testing.

Much of the fallout from those events is now entombed within Runit Dome. According to a photograph taken of Hamilton’s presentation slides, the 377-foot-wide crater in Enewetak Atoll contains groundwater samples with radiation levels 1,000 to 6,000 times higher than those found in the open ocean.

Some Marshallese who attended the presentation are skeptical about the agency’s conclusion that the dome is not leaking into the lagoon.

“What they’re saying is, here is the dome. And here, in the lagoon area, there is radiation. ... But as far as leaking from the dome, we don’t think that’s the case?” said James Matayoshi, mayor of Rongelap Atoll, one of the atolls contaminated by fallout from the nuclear testing program. “That doesn’t make any sense.”

Extending the incredulity further, Matayoshi and others noted that Hamilton presented a short animation of the dome, showing it rise and fall with the tide — suggesting seawater is freely flowing in and out of the containment zone.

“It looked like it was breathing,” said Matayoshi, who was interviewed in Majuro several days after the presentation.

Anne Stark, a spokeswoman for the Department of Energy, declined to comment on the presentation because Hamilton’s work had not yet been peer-reviewed or published. According to people at the meeting, the research is contained in an unpublished report.

The U.S. began construction on the dome in 1977, after the Marshallese had demanded for decades that U.S. officials clean up the waste.

Many Marshallese from the northern atolls of Enewetak, Bikini and Rongelap were evacuated during the testing program and forced into perpetual migration. In Enewetak, for instance, an entire island was vaporized.

Between 1977 and 1980, the United States enlisted roughly 4,000 U.S. soldiers and subcontractors to clean the site. Many said they were inadequately protected. They excavated soils from Enewetak and elsewhere and turned the soil into a concrete slurry, which they poured into an unlined crater on Runit Island, left behind by the Cactus bomb. They sealed it with a clean concrete top 18 inches thick, creating what is now called the Tomb.

In 1980, the people of Enewetak were told by the U.S. government it was safe to return home.

But there have been lingering worries about the atoll’s safety. The U.S. government told the Marshallese the dome was a temporary fix. It’s now been nearly 40 years. This latest news didn’t alleviate any of those concerns, said Holly Barker, a professor of anthropology at the University of Washington in Seattle. Barker is a member of the Marshall Islands’ three-person National Nuclear Commission — a government-mandated committee charged with seeking justice for nuclear-related injuries and damage.

The basic takeaway from the presentation, said Barker, is the lagoon is so contaminated, any leakage from the dome is negligible.

Which raises the question, “in what way was Runit a cleanup?” Barker said.

Steve Simon, a researcher who has worked extensively on radiation issues in the Marshall Islands and now works for the National Cancer Institute, said the conclusions presented at the meeting were not surprising or alarming.

“This isn’t news,” said Simon, who was not at the presentation and was only provided with the conclusions delivered at the meeting by a reporter. “We’ve known for decades that the material in the dome is radioactive as well as the surrounding soil and sediment.”

He says data gathered by the Department of Energy over the last several decades has been consistently reliable and shows the atoll is safe to live in, as long as people avoid eating large amounts of food that have been grown on or near Runit, including the clams.

![High levels of radiation in giant clams led one expert to ask “in what way was Runit [Dome] a cleanup?”](https://ca-times.brightspotcdn.com/dims4/default/81e065a/2147483647/strip/true/crop/2048x1365+0+0/resize/1200x800!/quality/75/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fcalifornia-times-brightspot.s3.amazonaws.com%2F3b%2Fd1%2Fa26d678de091599779cced3388fe%2Fla-1559008863-8ge1c3zj3g-snap-image)

If they had eaten a few, however, he said they shouldn’t be alarmed.

“We don’t measure radiation exposures as a one-time event. We calculate exposure over a year or a lifetime,” he said.

He said overall the radioactivity in the Marshall Islands was fairly low. There are a few hot spots, but they are well known and people know to avoid them.

“This is where the U.S. government is missing the mark,” Barker said. “They give the Marshallese numbers and tell them it’s up to them to decide what risks they want to expose themselves to. But they’re not looking at how the Marshallese interact with these places. They’re not bothering to understand.”

She noted that in the U.S., places that have been irradiated, such as Hanford Site, a decommissioned nuclear weapons complex in Benton County, Wash. — the first full-scale plutonium production reactor in the world — are surrounded by fences and closed off to the public.

A visit to Runit last summer by The Times indicated there was no fence or sign warning people to stay away or avoid eating foods grown on the island. Indeed, there was evidence that people had camped and eaten coconut crabs — large, baseball-mitt-sized crabs that clamber through the thick underbrush and palms of the island.

There are “a lot of uncertainties” about plutonium in the dome’s groundwater and lagoon sediments, said Rhea Moss-Christian, another member of the three-person nuclear panel. She said the Marshall Island government was working on getting independent analyses of Runit Dome and the lagoon.

Lucinda Anitok, 35, from Sedro-Woolley, Wash., is a descendant of Runit landowners. She said the U.S. testing program in Enewetak had devastated her family. Her grandmother, who was raised on Enewetak, had thyroid cancer. Her mother, who was born there, had cervical cancer. And her sister had leukemia.

“What happened there was wrong,” she said. “It ruined, and is still harming, many people’s lives.”

At a Marshall Islands’ Constitution Day celebration on Friday in Auburn, Wash., which featured dignitaries from the Marshall Islands — including Ken Kedi, the parliamentary speaker, and the Islands’ minister of internal affairs, Amenta Matthew — the legacy of the testing program could still be felt.

Anitok and her husband, David, have traveled extensively educating young Marshallese about the past — making sure they know their nation’s history and their ancestors’ legacy.

“It’s important that my grandmother, my mother and my ancestors are not forgotten,” she said. “We can’t — and we won’t — forget.”

Times staff writer Rust reported from Seattle and Menlo Park, Calif., and staff photographer Carolyn Cole reported from Majuro, capital of the Marshall Islands.