Astronomers find what may be the oldest galaxy ever seen

- Share via

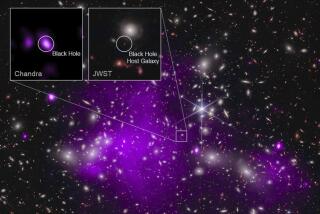

Astronomers said this week that they found a distant galaxy that could be the oldest object ever observed in the universe.

The discovery could help them better understand the early days after the Big Bang — more than 13 billion years ago when the first stars were born.

But some scientists were more intrigued by the vast emptiness that apparently surrounds the ancient galaxy.

“The most interesting thing is the galaxies they didn’t detect,” said Mark Dickinson, an astronomer at the National Optical Astronomy Observatory in Tucson, who wasn’t involved in the discovery.

The galaxy, known as UDFj-39546284, was spotted in a patch of sky called the Hubble Ultra Deep Field. Based on their understanding of how the universe evolved, the scientists who scoured that region had expected to find about five galaxies that were roughly the same age. But they saw only the one.

“That told us very dramatic things are happening with galaxy generation” at that time, said UC Santa Cruz professor Garth Illingworth, a member of the research team that published its findings Thursday in the journal Nature. “We’re getting close to the era of galaxy birth.”

The galaxy in question is quite small, with a mass less than 1% that of our Milky Way. It is also gassy and composed of “fuzzy bright blue blobs of tens of millions of stars,” Illingworth said.

If the team’s estimates of its age are correct, the galaxy’s redshift — a measure of how fast the galaxy and the Earth are moving away from each other because of the expansion of the universe — is around 10. That means it existed a mere 480 million years after the Big Bang, when the universe was less than 4% of its current age.

The earliest galaxies previously identified have redshifts of around 8.5. They emitted their light about 100 million to 150 million years later than UDFj-39546284.

To find the galaxy, Illingworth, lead author Rychard Bouwens of Leiden University in the Netherlands and colleagues collected images of the Hubble Ultra Deep Field in 2009 and again in 2010. They scrutinized the data looking for objects that were extremely faint and very red.

After numerous tests, Illingworth said, they were left with just one “tantalizing” object.

Experts caution that they can’t be certain UDFj-39546284 is as old as the team suspects until the light it emits can be analyzed more precisely with a spectrograph.

“There’s no proof that it’s at this great distance other than its color,” said Caltech astronomer Richard Ellis, who was not involved in the research.

Pinning down the ages of extremely old objects in space is tricky because the light they emit is so dim.

Last year, the Bouwens team released a draft paper describing three candidate galaxies with redshifts of about 10. The paper was not published because new data in 2010 showed that the objects were “spurious”.

Illingworth said the Nature paper is based on stronger data. He estimated that the chance that UDFj-39546284 would turn out to be something other than a galaxy is about 10%.

The ancient galaxy — along with its apparent lack of neighbors — will help astronomers understand what happened to the vast clouds of hydrogen gas that shrouded the early universe. Many believe light from early galaxies and stars ionized the hydrogen and made the universe more transparent. But the Bouwens paper suggests that there may not have been enough of those galaxies and stars around to do so, said Dickinson of the National Optical Astronomy Observatory.

“They’ve done the best job of quantifying what we can see — and it turns out to be not very much,” he said. “It seems to be nowhere near enough to be responsible for ionization.”

Ellis was more skeptical. “It’s a stretch to base a discussion on only one object,” the Caltech astronomer said. “If you met one person, could you estimate the population of a town?”

No one will know until more data appear, the experts said, and that could take time.

Illingworth said questions like these make the case for completion of the James Webb Space Telescope, a planned successor to the Hubble telescope that may be powerful enough to deliver the data the astronomers need, but which has become bogged down in budget troubles.

“This is as far as we’ll go with Hubble,” Illingworth said. “It’s pushing the limits of what we can do.”