Coronavirus Today: The virulence of anti-Asian hate

- Share via

Good evening. I’m Amina Khan, and it’s Friday, March 26. Here’s the latest on what’s happening with the coronavirus, plus ways to spend your weekend and a look at some of the week’s best stories.

Over the past year, the pandemic has taken a toll on Americans who have found themselves cut off from family, friends and many forms of shared public life. It has upended people’s livelihoods and destabilized their housing. It has meant trying to decipher people’s muffled voices and half-hidden expressions through masks all while trying to stay a safe distance. Sometimes, it has meant risking confrontation with, and infection by, those who won’t.

All of these changes have been stressful and isolating for everyone. But for many Asian Americans, they’ve been exacerbated by a deep reservoir of racist antagonism that has only become more apparent — and sometimes more violent — during the pandemic.

Take Syl Tang, who boarded an elevator in New York City this month and was accosted by a woman who pulled up the corner of her eye in a gesture meant to mock Asians, then launched into a coronavirus tirade and claimed a “foreigner” had given her the virus.

It didn’t end there. Others on the elevator chimed in and said that COVID-19 had been “brought here.” Tang decided to say something.

“I would like you to know that I’m vaccinated,” said Tang, who wanted the woman to hear that she spoke English fluently and without an accent.

Tang can tick off several other disturbing incidents where she has faced this kind of racist hostility, and she’s not alone. Even before the pandemic, this kind of verbal harassment has been a far too common part of life for Asian Americans — usually not rising to physical violence but sometimes feeling like a window into a deeper well of hate, my colleague Brittny Mejia reports.

But anti-Asian sentiment in the U.S. has been stoked over the course of the pandemic, including by former President Trump’s inflammatory rhetoric concerning the virus’ origins. Anti-Asian violence has been on the rise since coronavirus shutdowns began last March, research shows.

Together with the mass shooting in Atlanta last week that killed eight people, six of them Asian women, it has underscored the more commonplace incidents of bigotry and left its victims struggling to find the best way to respond: Do you try to laugh it off and make the moment end? Do you silently walk away? Do you explain why the words were hurtful? Or do you give the person a well-deserved telling-off? And what happens if the encounter turns violent?

Los Angeles musician John Bach says that when he’s on tour, especially through the Deep South and the Midwest, he tries to deflect racist comments and maintain a friendly demeanor.

While at a hair salon last March, Manjusha Kulkarni overheard two white women saying that Asians spread disease because of the food they eat. She tried politely to correct them. Still, she was shaking when she did it.

“I would feel worse not doing something than doing something, but that’s in environments that were still safe,” said Kulkarni, the executive director of the Asian Pacific Policy and Planning Council and the co-founder of Stop AAPI Hate. “If you asked me, ‘Would I do it alone around a big man?’ No, I would not.”

All of us are navigating the risk of coronavirus exposure anytime we leave home and venture out in the world. But it’s worth remembering that for many us, in these shared public spaces, the virus is not the only threat.

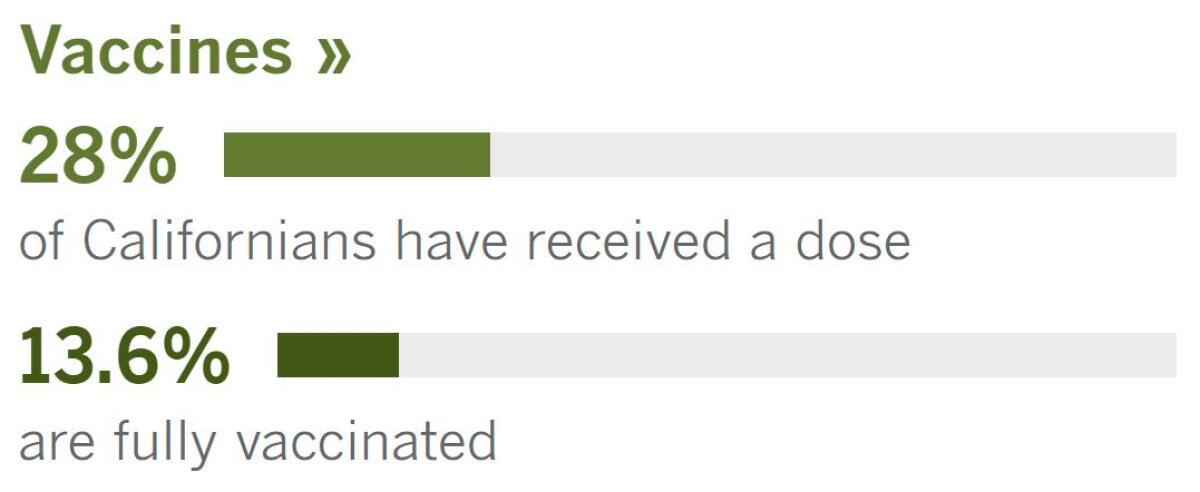

By the numbers

California cases and deaths as of 7:04 p.m. Friday:

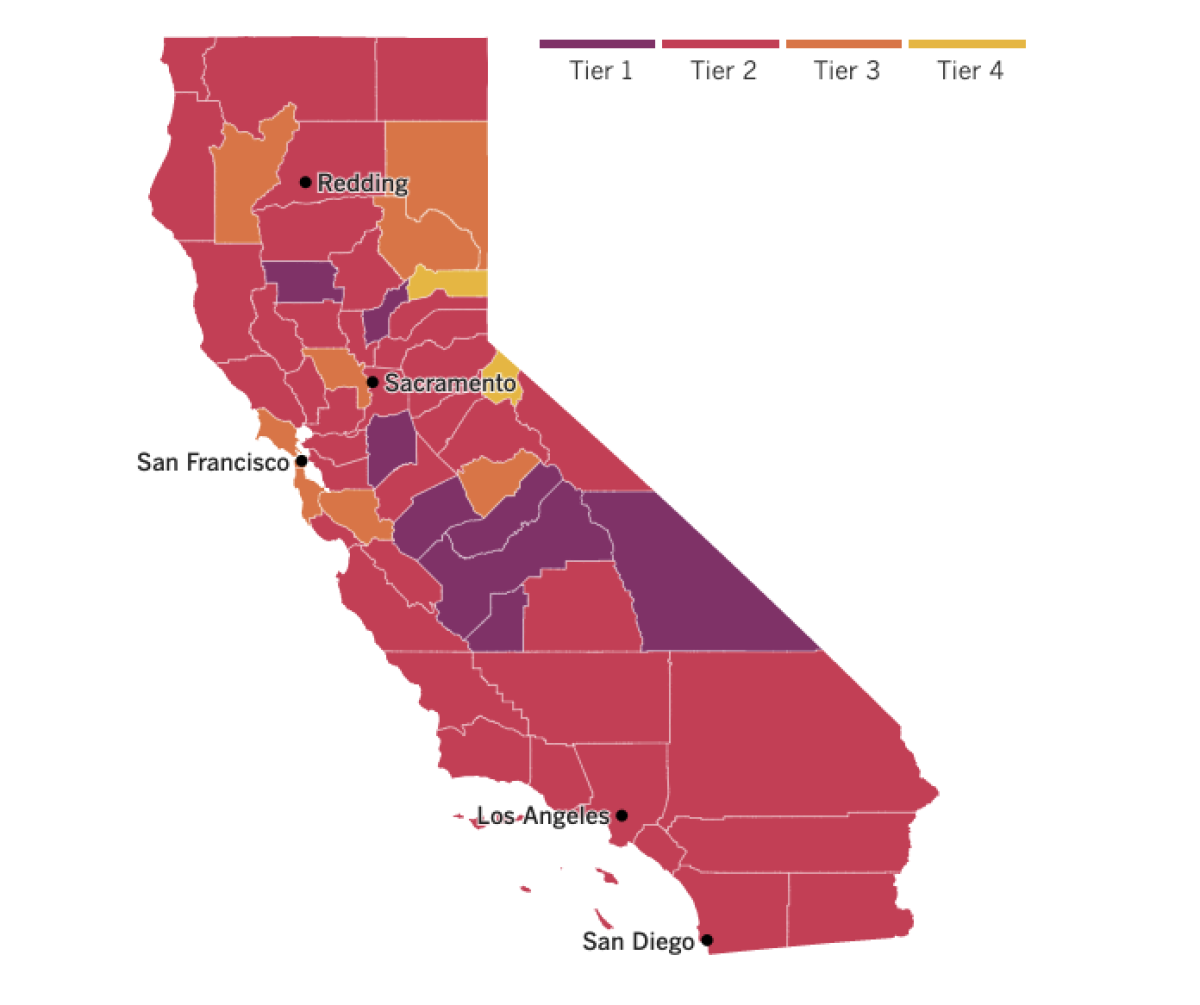

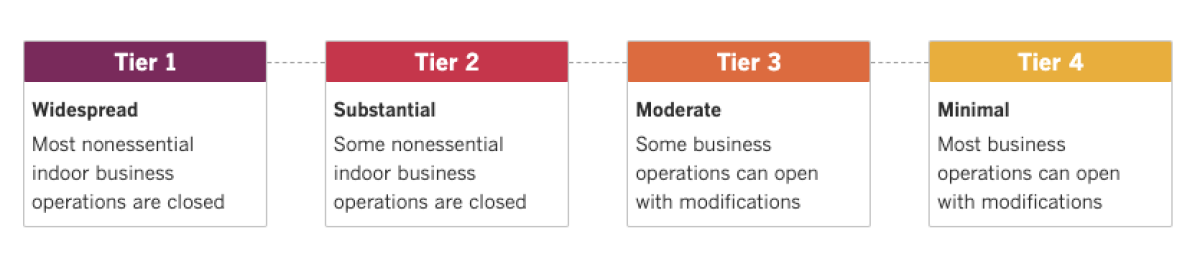

Track California’s coronavirus spread and vaccination efforts — including the latest numbers and how they break down — with our graphics.

See the current status of California’s reopening, county by county, with our tracker.

What to read this weekend

The real vaccine skeptics

So much has been written about the unique challenges of persuading Black Americans to get vaccinated against COVID-19. Whether due to infamous examples of racism in the past or their lived experience of healthcare disparities in the present, Black adults have reason to be wary of the medical establishment. Yet Black Americans, after some initial hesitance, now say they want the vaccine at the same rate that white people do, my colleague Doyle McManus writes.

There’s another group of Americans who are more skeptical of COVID-19 vaccines: Republican men. Fully 49% of GOP men told pollsters in a recent survey that they do not intend to get vaccinated. That’s a higher percentage of refusers than any other demographic group. For the sake of comparison, only 6% of men who are Democrats share this view. And among Black men and women, just 25% said they didn’t plan to take the vaccine.

“We’ve never seen an epidemic that was polarized politically before,” said Robert J. Blendon, a health policy scholar at Harvard.

Why should we care about the vaccination plans of men who identify as Republicans? Because their decision not to get vaccinated puts the rest of us in danger, too, McManus writes. They can become infected with the coronavirus and pass it on to others. Their resistance makes it harder to achieve “herd immunity,” the point at which the virus can no longer find new hosts to infect and the pandemic comes to an end. The longer that takes, the more people will get sick.

The ‘long haulers’

Larry Searight awakens each morning, often before dawn, to the kind of pandemic nightmare that has roiled the sleep of many over the past year.

A scourge that never ends. A world that thaws and moves on but leaves him stuck and unable to keep up. Terrifying physical sensations that descend without warning and disappear just as suddenly. Friends and doctors turning away in disbelief. The mounting losses — of joy, of taste and smell, of mental firepower.

A year after a two-week episode of chills, cough and exhaustion, Searight is at the daily mercy of a revolving array of symptoms — many of them profoundly disabling — that come and go without warning. He’s one of hundreds of thousands of Americans, and likely millions more across the world, who have shaken off a coronavirus infection but still contend with persistent, and perplexing, aftereffects.

Their numbers go well beyond the minority of patients who were put on ventilators, or who nearly died because their immune systems overreacted to acute infection. Patients who have sustained organ damage face medical challenges that are complex, but not mysterious. But people like Searight are an enigma on many levels. Let Melissa Healy be your guide to what’s come to be known as Long COVID.

An epic outreach effort

The state of California has made it a priority to vaccinate people in underserved communities. And they’re underserved for a reason: Many do not have cars, reliable internet access, legal documentation or enough free time to search for an appointment, let alone show up for one.

So a vast, wildly varied network of grassroots volunteers is working the phones and hitting the streets. They’re knocking on doors in apartment complexes and mobile home parks. They’re chatting up street vendors and posting flyers on telephone poles. They’re pitching tents to set up temporary COVID-19 vaccination clinics in the park. When people won’t go to the vaccine, these volunteers will bring the vaccine to the people.

“We tried a little bit of everything,” said Dr. Wilma Franco, who runs the Southeast Los Angeles Collaborative, a coalition of local nonprofits that coordinated a vaccine drive in South Gate Park.

Much is riding on their success. Increasing vaccinations in high-need populations will make it possible for more schools to reopen and for more businesses to get back in the black. It can be grueling work, but rewarding as well. Check out this story by Maya Lau and Laura J. Nelson to see how these intrepid volunteers are pulling it off.

A therapist tested by the pandemic

Ariel Friedman, like many therapists, found herself on the front line of a growing mental health crisis as the pandemic shut down so much of normal life. And as she helped her patients battle malaise, isolation and fear, she was navigating those feelings herself, my colleague Emily Baumgaertner reports.

Friedman had been taught that therapy works in part because it’s held in a physical and emotional space that’s separate from the rest of life. But when the shutdowns hit, most of her clients lost that space overnight. Toddlers wailed and family members fought during virtual counseling sessions. Clients sometimes appeared more stressed at the end than they were at the beginning.

Meanwhile, the therapist was cramped in a shoebox San Francisco flat with her fiancé, who was recovering from an invasive back surgery while running a nonprofit from their living room. They were also experiencing a stress reaction that Friedman recognized: zigzagging between hypervigilance and denial. As with so many others, baking became an outlet to help her navigate the pressures of the pandemic: She whipped up lemon almond macaroons, cinnamon raisin bagels, challah and a citrus tart with grapefruit slices.

“I could point to it and say, ‘I put my energy here today, and this is what I created,’” she said. “Something sweet that tastes good — that was like my airplane oxygen mask, to help myself before helping others.”

Tiny testing company, big problems

There have been winners and losers in the COVID-19 economy. Curative has been both.

The privately held Los Angeles-area start-up gained a name for itself with a coronavirus test that promised accurate results if people would just cough and swab their mouths. No brain-tickling nasal swabs were required. The approach differed from established science, but the U.S. Food and Drug Administration authorized the test for emergency use.

Before long, the start-up transformed from fewer than a dozen employees to a juggernaut servicing mass testing sites at places like Dodger Stadium with revenue in the range of perhaps $1 billion. But the more the test was used, the more problems cropped up, including multiple reports of false-positive and false-negative results.

Curative’s story illustrates just how ill-equipped L.A. County, California and the nation were to respond to a public health crisis, my colleagues Laurence Darmiento and Melody Petersen explain. A debilitated public sector responded to an overwhelming catastrophe by opting to relax regulations and place its faith in companies that stood to profit from a once-in-a-century pandemic. It’s well worth a read.

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most.

What to do this weekend

Get outside. Join a community science program and keep an eye out for mating alligator lizards. One telltale sign? One lizard (a male) biting another (female) lizard’s neck or head and holding her that way for days. If you catch any in action, take photos and upload them to the L.A. County Natural History Museum’s website. Subscribe to The Wild for more on the outdoors.

Watch something great. Our weekend culture watch list includes “The Thanksgiving Play,” which stars Keanu Reeves, Bobby Cannavale, Heidi Schreck and Alia Shawkat in a reading of Native American playwright Larissa FastHorse’s satirical tale of white actors attempting to stage a culturally sensitive elementary-school Thanksgiving pageant. And in his Indie Focus newsletter’s roundup of new movies, Mark Olsen highlights “Nobody” by “John Wick” writer Derek Kolstad, about a mild-mannered family man (played by Bob Odenkirk) who goes back to his roots as a trained killer.

Eat something great. Try out these tasty recipes perfect for Passover, including gougères with leeks and mushrooms as well as matzo brei chilaquiles. Sign up for our Cooking newsletter for more mouth-watering meals.

Go online. Here’s The Times’ guide to the internet for when you’re looking for information on self-care, feel like learning something new or interesting, or want to expand your entertainment horizons.

The pandemic in pictures

When the pandemic gifted 71-year-old Gary Handman with a lot of free time, the retired librarian picked up his iPad and began drawing cartoons of his strange new life. Before long, his doodles became daily entries in his “Journal of the Plague Year.” One entry is a collection of pandemic inventions, including a contraption involving a red wagon, a barber and a hairdryer that keeps his glasses defogged while he’s wearing a face mask. Another entry finds him longing to be abducted by aliens just to get out of his house.

Columnist Nita Lelyveld, who introduces us to Handman, says his journal is a prime example of how the pandemic gave the lucky among us “much more room to be present in our lives. It has kept us from so much, but it also has kept us from running away from ourselves. It has provided the space required for us to dig deeper.”

Without the “national timeout” the pandemic provided, Handman would have frittered away his time running errands and buying things he didn’t really need, Lelyveld writes. “Instead, he drew and drew, and in the process, got better at drawing, he said. Absorbed as he was in a fulfilling endeavor, unlike his cartoon alter ego, he suffered very little angst. And out of a bad year he made something really good.”

Resources

Need a vaccine? Keep in mind that supplies are limited, and getting one can be a challenge. Sign up for email updates, check your eligibility and, if you’re eligible, make an appointment where you live: City of Los Angeles | Los Angeles County | Kern County | Orange County | Riverside County | San Bernardino County | San Diego County | San Luis Obispo County | Santa Barbara County | Ventura County

Practice social distancing using these tips, and wear a mask or two.

Watch for symptoms such as fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, shaking with chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat and loss of taste or smell. Here’s what to look for and when.

Need to get tested? Here’s where you can in L.A. County and around California.

Americans are hurting in many ways. We have advice for helping kids cope, resources for people experiencing domestic abuse and a newsletter to help you make ends meet.

We’ve answered hundreds of readers’ questions. Explore them in our archive here.

For our most up-to-date coverage, visit our homepage and our Health section, get our breaking news alerts, and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.