Coronavirus Today: 1 million U.S. deaths, and counting

- Share via

Good evening. I’m Karen Kaplan, and it’s Tuesday, May 17. Here’s the latest on what’s happening with the coronavirus in California and beyond.

We’ve marked a lot of grim milestones in this newsletter, but the one that came Monday puts all others to shame:

One million COVID-19 deaths in the United States.

That hardly seemed possible on Feb. 6, 2020, when 57-year-old Patricia Dowd died in San Jose. She came down with an illness that appeared to be the flu and seemed to be on the mend. Her unexpected death was initially blamed on a heart attack, but a couple of months later, health officials confirmed that she had been infected with the then-novel coronavirus. That made her the nation’s first official COVID-19 fatality.

COVID-19 wasn’t even in our lexicon the day Dowd died. The disease got its official name five days later, courtesy of the World Health Organization.

You would have needed an active imagination to predict that Dowd would be joined by 999,999 others in the U.S. alone. But she was. Sometime last week, the National Center for Health Statistics tallied the 1 millionth death certificate that listed COVID-19 as a primary or contributing cause of death. By week’s end, that provisional death toll was up to 1,000,659.

“A million things went wrong, and most of them were preventable,” said elder care expert Charlene Harrington of UC San Francisco.

The higher the number climbs, the harder it is to wrap your head around it. Here’s one way to look at it: It’s as if the country experienced a 9/11-sized tragedy every single day from Jan. 1 to Dec. 2.

No group of Americans has escaped COVID-19’s clutches, but some have had it worse than others. For instance, the U.S. has recorded deaths among children and even infants. But nearly 75% of deaths were in people 65 and older, even though that age group makes up only about 17% of the country’s population.

Men have accounted for 55% of the nation’s COVID-19 deaths, compared with 45% for women. This despite the fact that women outnumber men, especially in the oldest age cohorts with the highest fatality rates.

The lion’s share of deaths — 65% — occurred among white Americans. That’s largely because white Americans outnumber members of all other racial groups. But on a per capita basis, Black Americans, Latino Americans, Native Americans and Pacific Islanders had higher COVID-19 death rates.

The disease has been more lethal in rural communities than in urban ones. Up through Sunday, the cumulative mortality rate for residents of rural counties was 387 deaths per 100,000 people. In urban areas, that mortality rate was about 25% lower, at 287 deaths per 100,000 people.

As you may have the misfortune of knowing personally, these deaths are far more than abstract numbers.

Tonia Liddell has experienced two of them personally. Her mom caught the coronavirus in February 2020 when she was in an assisted living facility in Milwaukee and died at age 68. With lockdowns in place, Liddell waited until Memorial Day weekend to hold a celebration-of-life service. Then her uncle died of COVID-19 a few weeks after that.

“This pandemic,” Liddell said. “It’s ripped up my life.”

In Phoenix, Karen Garcia had been a nurse for just eight months when her hospital’s ICU started filling up with COVID-19 patients in late March of 2020. She feared for her own health and sometimes stayed in a hotel to shield her young children from any virus she might be carrying.

One of the first COVID-19 patients she lost was a man in his mid-30s who seemed to be in fine health before the coronavirus got him. It ravaged each of his body’s critical systems. In the end, it clogged his lungs.

“That situation really signified for me how real this pandemic was — and how bad it was going to get,” Garcia said. “Young, old, all races, the virus was taking the lives of anyone.”

And it’s not over. Over the last week, the U.S. has averaged 274 new deaths per day. That’s far fewer than the peaks seen in the last two winters. But with new cases back on the upswing, experts are reluctant to say the end is in sight no matter how many safety measures fall by the wayside.

“It’s still happening,” said Jennifer Nuzzo, who leads a new pandemic center at the Brown University School of Public Health in Providence, R.I., “and we are letting it happen.”

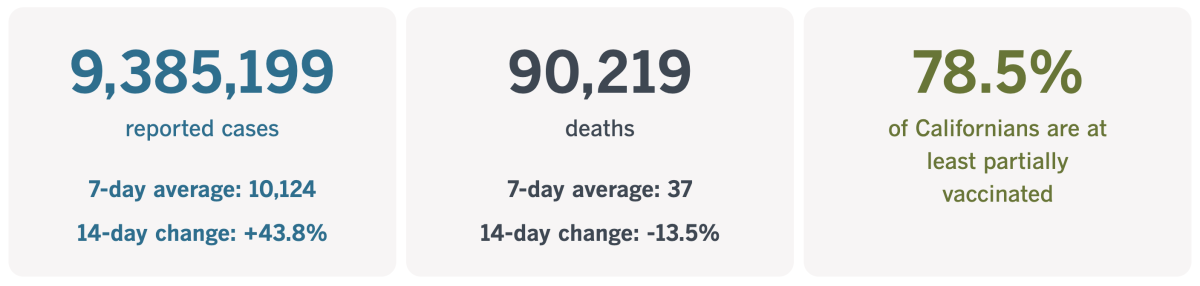

By the numbers

California cases and deaths as of 5:45 p.m. on Tuesday:

Track California’s coronavirus spread and vaccination efforts — including the latest numbers and how they break down — with our graphics.

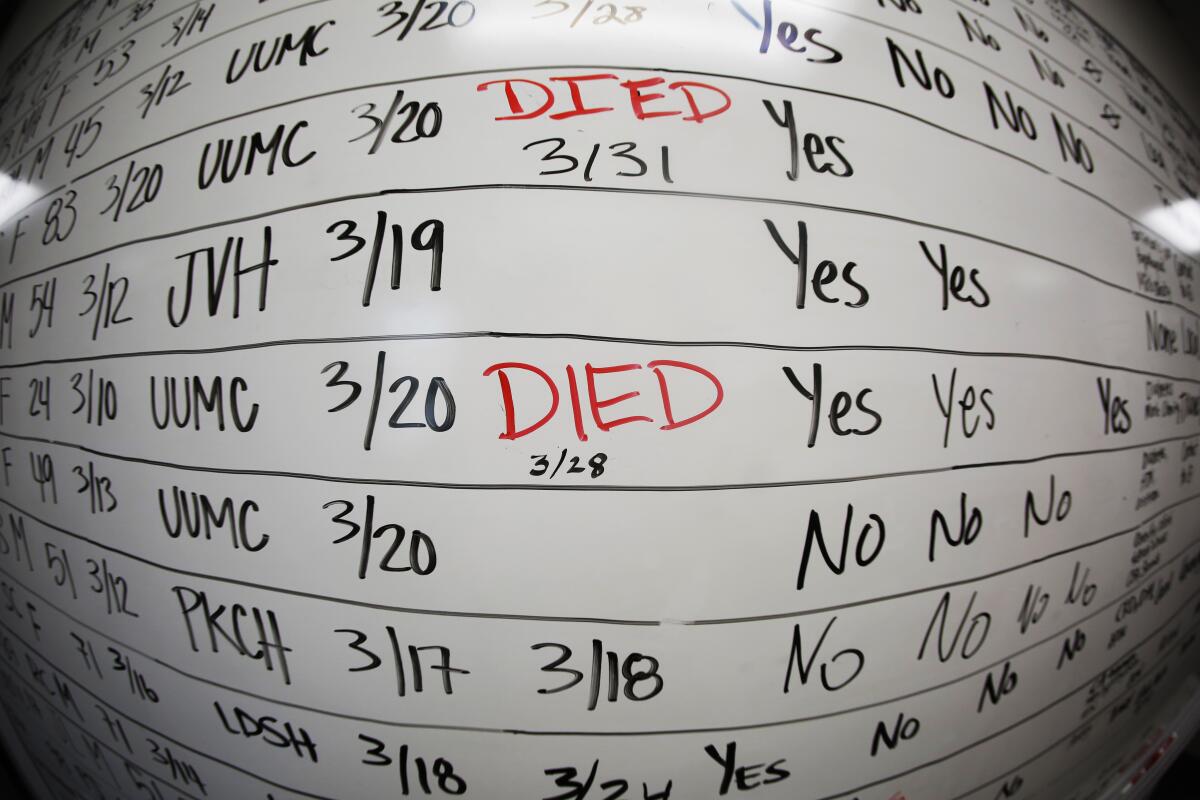

Bearing witness to COVID-19 deaths

Kevin Deegan, the senior chaplain at Providence Holy Cross Medical Center in Mission Hills, will never forget his first COVID-19 patient.

The man was alone in a room, on a floor that was eerily quiet. The only people who got near him were medical staff obscured by layers of personal protective equipment. The patient was gravely ill, and his daughter was coming to see him before he died.

Deegan approached the room and met Dr. Marwa Kilani, the hospital’s medical director of palliative care. Kilani relayed some sobering news regarding the man’s daughter: “We are not going to be allowed to let her in.”

So Deegan went downstairs to meet the daughter outside the hospital lobby. He called Kilani on his iPhone and handed it to her. Up on the ward, Kilani held her phone so the daughter could FaceTime with her father.

“She said: ‘I can’t be with you in person, but I see you. I love you. When you get to heaven, tell Mom, ‘I love you.’ I am going to be OK. You are going to be OK. Just rest. Just rest,’” the 36-year-old chaplain told my colleague Francine Orr.

While the daughter said goodbye, Deegan grappled with feelings of confusion, anger and helplessness. Then, he said, “she handed me the phone back, and I thought she was possibly upset, but when we stood up, she hugged me, and she said, ‘Thank you for letting me be with my dad.’”

It was a routine that would be repeated hundreds of times after that. At times, he juggled 10 video calls in a single day.

“There were some times I had multiple iPads going at the same time in different rooms,” Deegan said. “I’d have one iPad here, one iPad there, and I would be alternating back and forth.”

He knew he was helping people get through some of the hardest moments of their lives. But hearing their voices was almost unbearable.

“A few months in, I learned to say to the family, ‘I am going to step away and give you some privacy,’” he said. “Part of that was giving them permission to say what they wanted without me being there to interfere, but part of it was for my own self-care.”

Deegan also remembers when the hospital policy changed and relatives were allowed to say their farewells in person. In particular, he remembers the wife and two children of a longtime patient named Bob Harris.

Deegan and Kilani escorted the trio into Harris’ hospital room as nurses cried outside the door.

“It was tragic. It was beautiful. It was hard,” Deegan said. “It was all those things together.”

The thing is, the work of a hospital chaplain isn’t done in an empty chapel. It depends on being close to the people who need him.

“We cannot offer support unless we are present,” Deegan said. “Support cannot be done after the fact. I had to be here while it happened. I had to be here with them so when they looked to me and said, ‘This is really hard,’ I can say I know because I have been here too.”

Evidence of Southern California’s surges is still visible on the hospital’s floors. It’s in the form of faint marks left by strips of tape that marked the boundary of how far one could go without having to wear PPE. The more the hospital filled up with COVID-19 patients, the less territory remained in front of the tape.

“It was almost like a tide,” Deegan said. “The tide would come in and the tide would go out. It’s remarkable that a piece of tape was an indicator of how difficult work was going to be that day. Or how much we were being impacted by this virus.”

With coronavirus infection rates once again rising in California, he’s a little anxious about having to go back into surge mode.

“I don’t want to do that anymore,” he said. “But we’ll be here if that happens again. We are not going anywhere.”

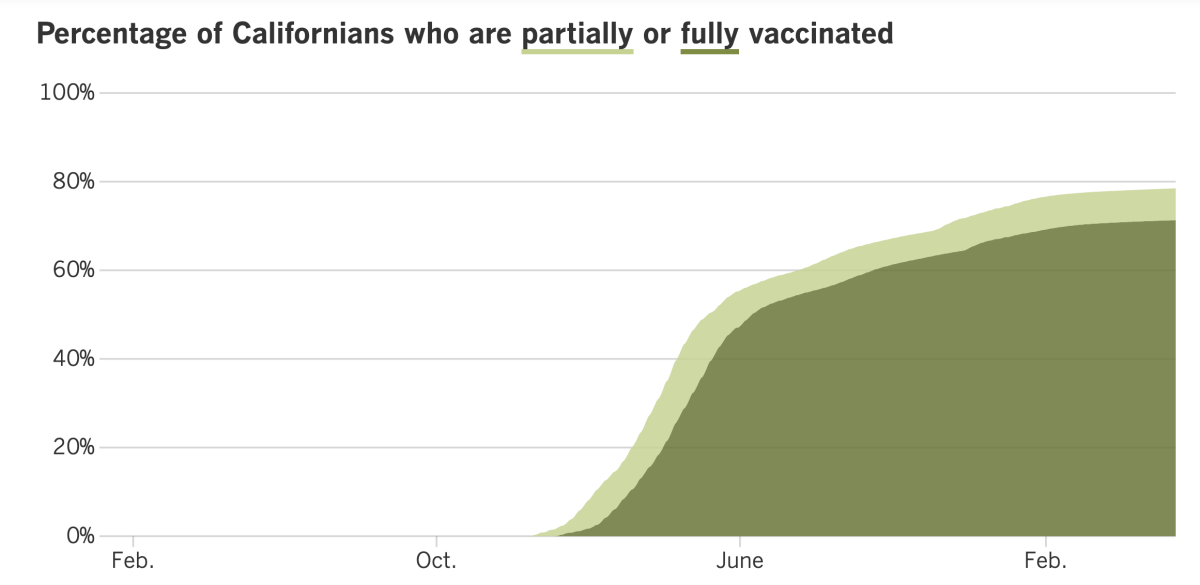

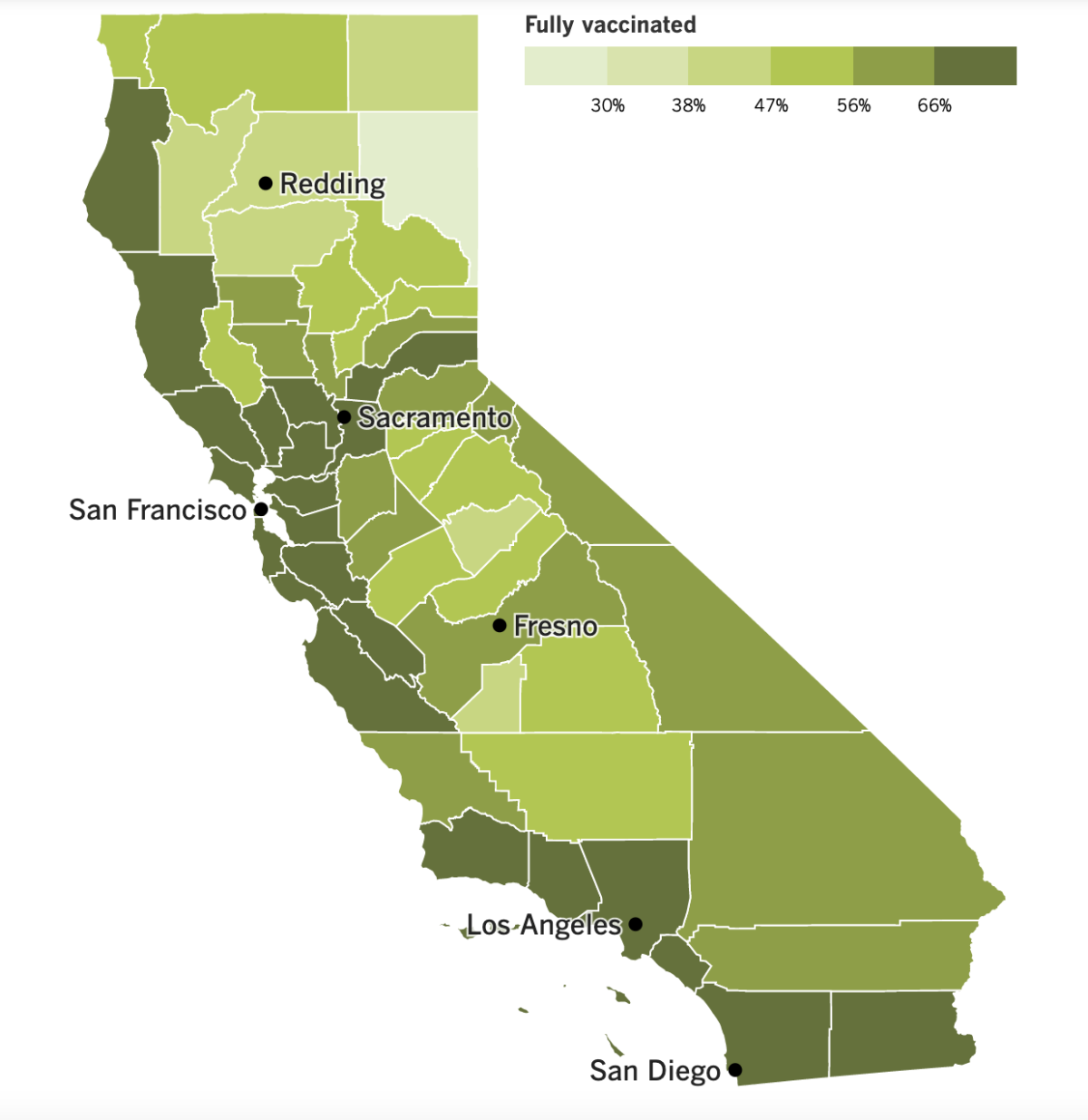

California’s vaccination progress

See the latest on California’s vaccination progress with our tracker.

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most.

In other news ...

The continued increase in coronavirus cases in Los Angeles County is making health officials nervous. Barbara Ferrer, the county’s director of public health, stepped up her appeals for Angelenos to mask up indoors.

The reason for her heightened concern: The number of new coronavirus cases here rose to more than 2,900 per day, a 16% increase over the previous week. That’s equivalent to 204 new cases per week per 100,000 residents — high enough to move from a low COVID-19 community level to a medium one, according to the standards set by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

It’s not just cases that are rising. Hospitalizations are up nearly 40% in the last two weeks, with 327 inpatients throughout the county. That includes 44 patients in ICUs. The county has averaged six deaths per day over the last week, according to The Times’ tracker.

Masks are still required on public transit and in transportation hubs in L.A. County, including airports. But since March 4, there has been no universal requirement to wear them in stores, offices, schools or other indoor public spaces.

The big question for many residents is how much longer that will be the case. County officials have said they’d reinstate their mask order if the COVID-19 community level moved into the high level. That would mean having at least 200 new coronavirus cases per 100,000 people per week plus having at least 10% of new hospital admissions or at least 10% of currently hospitalized patients diagnosed with COVID-19. Both of those scenarios are still a ways off.

As for the increase in new cases, my colleague Rong-Gong Lin II reports that infections are rising fastest among the county’s wealthier residents.

An analysis of communities with at least 5,000 residents revealed that the highest case rates were in the Los Angeles neighborhoods of Carthay, Rancho Park, Playa Vista, Century City, Pacific Palisades, Cheviot Hills, Venice and Hollywood Hills, the unincorporated coastal community of Marina del Rey and the city of La Cañada Flintridge. The case rates in these 10 communities were about three to five times higher than the countywide average.

Cases are also rising — albeit more slowly — among poorer residents, who are more likely to become seriously ill if infected. Among neighborhoods with at least some cases, the 10 with the lowest case rates were the cities of Compton, Paramount, Lynwood, Azusa, El Monte, Lancaster, the Los Angeles neighborhoods of Vernon Central, Westlake and Boyle Heights and the unincorporated community of Florence-Firestone. The rates in these communities were one-third to one-half that of the countywide average.

“This is similar to what we saw at the beginning of our earlier surges, where initially case rates rose first in better resourced communities, only to be followed by steeper increases in lower-resourced communities,” Ferrer said.

In Sacramento, state lawmakers have launched an ambitious effort to improve the care offered in nursing homes. Among other things, it would require the current owner or operator of a nursing home to be licensed by the state. That may sound like common sense — and that’s how it works in most places — but in California, “nursing home owners and operators can operate without a license even after they’ve been denied a license,” said state Assemblyman Al Muratsuchi (D-Torrance), author of the reform bill.

Right now, an owner or operator who can’t get a license can work around that by partnering with a former owner who is licensed. Muratsuchi’s bill would require prospective new owners or operators to apply for a license first, and the state would have to reject their applications if they didn’t meet financial standards, if other homes they operated had a poor track record, or if other problems were found. Unlicensed nursing homes wouldn’t be able to admit new residents and would lose Medi-Cal funding.

If the bill becomes law, it would become a model for other states. The industry says it’s an overreach. As of Tuesday, 9,716 Californians have died in nursing homes. That’s 13% of all COVID-19 deaths in the state.

Moving on to Washington, President Biden last week hosted his second virtual Global COVID-19 Summit. The urgency to address the pandemic has lessened considerably since the first summit eight months ago.

“We must remain vigilant against this pandemic and do everything we can to save as many lives as possible,” Biden said in a statement.

That includes appropriating more money for COVID-19 tests, vaccines and treatments, the president said. Congress has been cool to his latest request for $22.5 billion to fight the pandemic. In the meantime, his administration announced Tuesday that it will send eight free home test kits to U.S. households that want them. You can request yours by going to COVID.gov/tests or calling (800) 232-0233 (TTY [888] 720-7489) between 5 a.m. and 9 p.m.

Apparently, test kits aren’t in very high demand. Around the world, coronavirus testing is 70% to 90% lower in the second quarter of the year than it was during the first quarter, when Omicron was surging.

Experts lament the drop-off, saying that testing should actually be on the rise, especially in places where new subvariants of Omicron are taking hold. Without the information tests would reveal, the pandemic’s course is harder to track.

“We’re not testing anywhere near where we might need to,” said Dr. Krishna Udayakumar, director of the Global Health Innovation Center at Duke University. “We need the ability to ramp up testing as we’re seeing the emergence of new waves or surges.”

Shanghai’s 25 million residents got some good news Monday: The number of people still under strict lockdown has fallen below 1 million.

Viral transmission among unquarantined residents has been eliminated in 15 of the city’s 16 districts, according to Vice Mayor Zong Ming. Supermarkets, restaurants and malls were allowed to reopen with limits, including a requirement for contactless transactions. The city’s subway system is still closed, and movement around China’s second-largest city is still limited.

“The epidemic in our city is under effective control,” Zong said. “Prevention measures have achieved incremental success.”

Next door in North Korea, Supreme Leader Kim Jong Un has mobilized the military to respond to a surge in suspected coronavirus infections.

The Omicron variant was detected in the capital, Pyongyang, on Thursday. The following day, health officials reported six deaths and 350,000 illnesses. On Monday, there were eight more deaths and nearly 393,000 new infections.

Kim acknowledged that the coronavirus was probably responsible for the outbreak, which he said was causing “great upheaval.” Outside experts say the situation is probably more dire than officials let on. And the worst may be yet to come, warned Dr. Poonam Khetrapal Singh, the World Health Organization’s regional director for Southeast Asia.

“With the country yet to initiate COVID-19 vaccination, there is risk that the virus may spread rapidly among the masses unless curtailed with immediate and appropriate measures,” she said in a statement.

Your questions answered

Today’s question comes from readers who want to know: How are COVID-19 deaths counted in the U.S.?

Not terribly well.

It’s an open secret that the official tallies are an undercount. The strongest evidence comes from a measure of so-called excess deaths. That’s the difference between the expected number of deaths and the number that actually occurred.

A study in the early months of the pandemic estimated that the true COVID-19 death toll in the U.S. was 28% higher than the official tally. An influential research team in Seattle has posited that about half of the world’s COVID-19 deaths weren’t recognized as such.

There are several reasons for the undercount, starting with the fact that the country didn’t always have enough of the coronavirus test kits needed to make a definitive diagnosis. Plus, some of the early tests gave inaccurate results. Even when people with confirmed coronavirus infections died after experiencing a COVID-like illness, their death certificates may have listed another cause of death, such as pneumonia.

That said, the tallies we do have are not in perfect alignment. In fact, the CDC reports different figures on different websites.

The one that crossed the 1-million threshold first came from the CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics. On Monday, the NCHS reported that through the end of last week, 1,000,292 death certificates had listed COVID-19 as either the underlying cause of death or a contributing factor. That figure is considered provisional; indeed, it was raised to 1,000,659 on Tuesday.

Another approach is to count people who were diagnosed with COVID-19 and then died in a hospital. That’s the kind of data Johns Hopkins University has been gathering and posting on its COVID-19 Dashboard. The university’s tally was several hundred deaths shy of 1 million when the NCHS updated its figures on Monday morning. As of Tuesday evening, that count was 1,000,148.

The CDC’s COVID Data Tracker lags behind JHU’s dashboard by a few thousand deaths. Its count sums up the deaths reported to the agency from states, counties, the District of Columbia and U.S. territories. On Tuesday evening, the COVID Data Tracker listed 997,468 deaths.

It’s hard to say which method is best. With apologies to Leo Tolstoy, all data that are inaccurate are inaccurate in their own way.

We want to hear from you. Email us your coronavirus questions, and we’ll do our best to answer them. Wondering if your question’s already been answered? Check out our archive here.

The pandemic in pictures

We return to Providence Holy Cross Medical Center in Mission Hills, this time to the stairwell. That’s Chaplain Kevin Deegan sprinting his way up to the third floor.

During the pandemic, this overlooked part of the hospital came to hold special significance for Deegan.

“The stairwell is the only place that wasn’t affected by COVID,” he explained to Orr, who also took the photos of the chaplain. “It’s the space in the hospital that you can forget — intentionally forget what has been happening. And for that small moment, coming up the stairs — the ability to forget and not have to think about COVID — can be a sacred space.”

Resources

Need a vaccine? Here’s where to go: City of Los Angeles | Los Angeles County | Kern County | Orange County | Riverside County | San Bernardino County | San Diego County | San Luis Obispo County | Santa Barbara County | Ventura County

Practice social distancing using these tips, and wear a mask or two.

Watch for symptoms such as fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, shaking with chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat and loss of taste or smell. Here’s what to look for and when.

Need to get a test? Testing in California is free, and you can find a site online or call (833) 422-4255.

Americans are hurting in various ways. We have advice for helping kids cope, as well as resources for people experiencing domestic abuse.

We’ve answered hundreds of readers’ questions. Explore them in our archive here.

For our most up-to-date coverage, visit our homepage and our Health section, get our breaking news alerts, and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.