To prevent brain damage, soccer players should keep ‘head counts’

- Share via

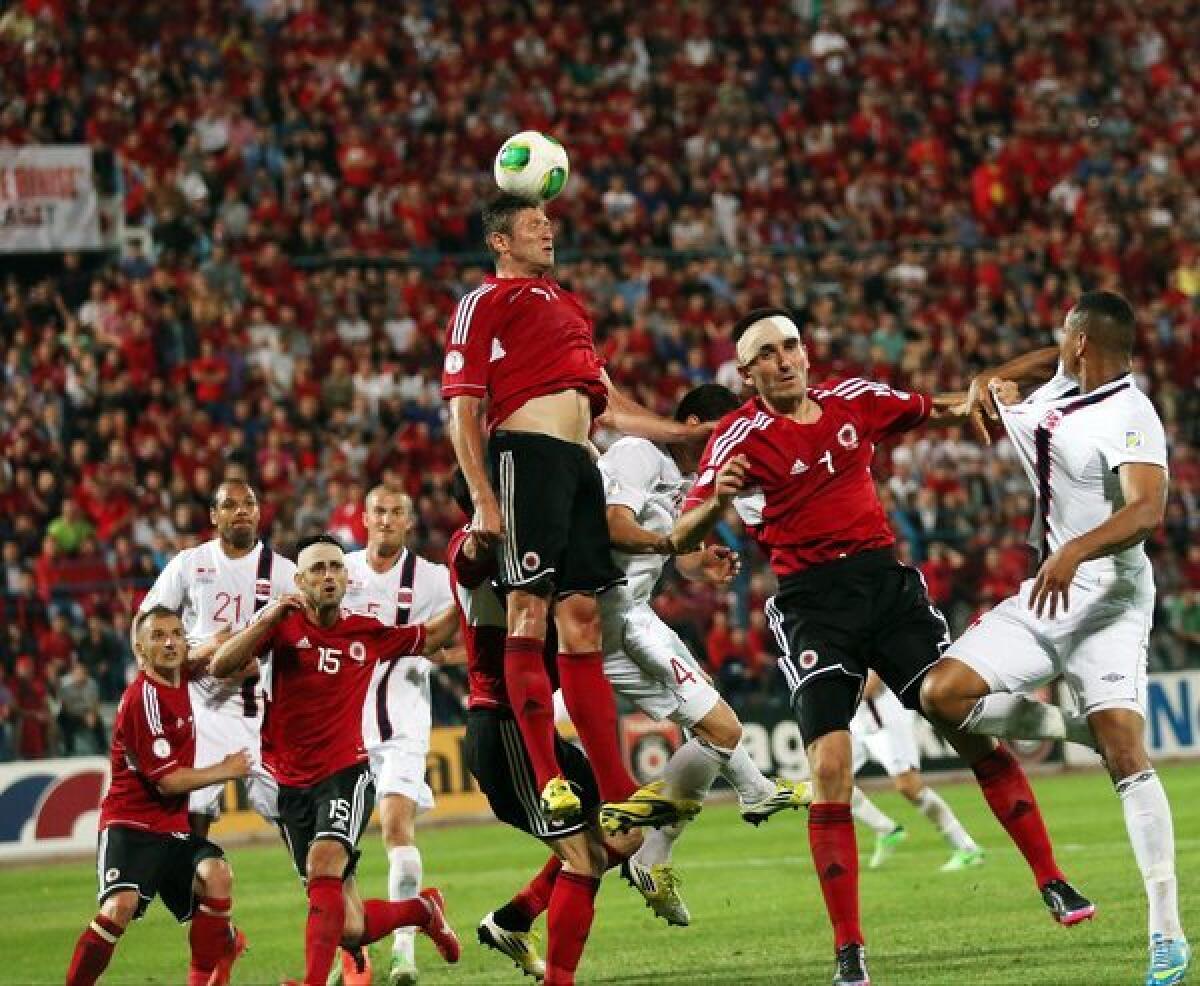

Heading the ball is a key soccer skill, but a new study finds that players who headed the ball frequently were more likely to suffer brain injury and damage their memory than their fellow players who were a little less headstrong, so to speak.

While sports like football (the American variety) and ice hockey garner most of the attention when it comes to concussions and other forms of traumatic brain injury (TBI), soccer is an intense physical sport for which the head can be as important as the foot. But since research hasn’t linked heading to concussions, players, coaches and medical professionals have generally stayed on the sidelines with regard to its health risks.

“For many people, it’s beyond belief that minor injuries could be a problem,” said Dr. Michael Lipton, a neuroradiologist at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York City and lead author of the study published online Tuesday by the journal Radiology.

Lipton said he hasn’t headed a ball himself since he played youth soccer. But he is intently interested in the cumulative effects of repetitive TBI. Soccer provided a nice venue for his research.

“With soccer, we know we have people who are going to experience exposure -- who are going to head the ball -- and we have a way to quantify that exposure,” he said.

To investigate the issue, Lipton and his colleagues interviewed 37 adult league soccer players from New York City and took high-tech scans of their brains using an MRI technique called diffusion tensor imaging. They also asked the players how often they played soccer and approximately how often they headed the ball, and they gave the players a battery of neurocognitive tests.

They divided the players into three groups – low heading, medium heading and high heading – and found that players who headed the ball the most had the lowest scores on memory tests, on average. They also had the lowest average scores for a metric called fractional anistropy (FA), which measures the health of the brain’s white matter -- the billions of nerve fibers that connect different parts of the brain. Low FA scores have also been found in people who have suffered concussions.

These findings were independent of players’ concussion history and demographic factors, which were controlled for in the study.

The researchers found no link between heading and players’ attention, ability to track visual stimuli or ability to manage complex cognitive tasks.

The relationship between heading and traumatic brain injury was not simply a linear one, with more heading leading to more injury. Instead, the researchers discovered that players could safely head the ball 885 to 1,550 times a year without experiencing FA problems; the threshold was almost 1,800 headers for memory-related difficulty.

There were some players below the thresholds who experienced FA and memory problems, suggesting that some individuals may be more sensitive to heading the ball.

However, Lipton cautioned players not to dismiss the potential risks of excessive headers.

Lipton suggests that soccer start keeping a “head count” to monitor the number of headers players use in a given game. The head count would be analogous to the “pitch count” in baseball that ensures pitchers don’t throw too many pitches in a single outing.

Allen Iverson’s objections aside, practice is also important to consider, Lipton said. The number of headers is usually greater in practice than in game situations, although they are made at lower speed.

Should David Beckham have been wearing a helmet during his years with Manchester United, Real Madrid and the Los Angeles Galaxy? Not so fast, Lipton cautioned.

“We can’t yet infer a definitive cause and effect from this study,” he said. The study was based on a small sample size, was heavily skewed towards male subjects (28 men, nine women), and was based on data collected at a single point in time.

But more research is on the way. Lipton’s team recently landed a $3 million grant from the National Institues of Health to extend the work.

In the meantime, soccer moms, if you’re concerned about your kids’ well being, just encourage them to be goalies.

You can read a summary of the study online here.