Chemistry on computers? Nobel Prize goes to scientists who led the way

- Share via

A University of Southern California professor and colleagues from Stanford and Harvard universities were awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry on Wednesday for their pioneering use of computer modeling programs to help predict complex chemical reactions.

Their work, which began in the 1970s, has revolutionized chemistry research, where scientists now work with computers as much as they do with test tubes.

“Chemical reactions occur at lightening speed,” read an announcement from the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in Stockholm. “In a fraction of a millisecond, electrons jump from one atomic nucleus to the other. Classical chemistry has a hard time keeping up. … Aided by the methods now awarded with the Nobel Prize in Chemistry, scientists let computers unveil chemical processes.”

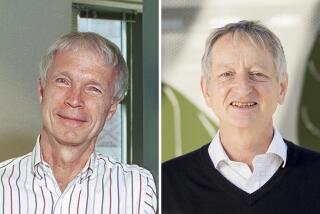

Arieh Warshel, 72, of USC; Michael Levitt, 66, of Stanford; and Martin Karplus, 83, of Harvard, were each recognized for devising computer programs that blended elements of classical chemistry and quantum physics -- where atomic particles such as electrons behave in a dualistic and unintuitive manner.

Their work, according to the academy, has led to a deeper understanding of molecules essential for life, as well as those used in industrial and pharmaceutical processes.

Ironically, much of this change in chemical research has occurred outside the public eye, and the prize winners said it still remains an uphill battle to persuade even fellow scientists that computers are important chemistry tools.

At a news conference early Wednesday, Warshel joked that many people believed that computers were best used to stream movies, “but not to understand.”

Warshel and the others said they hoped that their recognition by the Nobel Committee would help to change this view.

An Israeli and U.S. citizen, Warshel told reporters at the news conference that he was awakened at 2 a.m. by a telephone call with the news.

“First I checked to see if they were talking in a Swedish accent to be sure this was not a prank,” he joked. “Then I was very happy.”

One of the next calls he got was from Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who congratulated him. Warshel said the prime minister did not understand the nature of his work, but after a minute-long explanation from the professor, Netanyahu understood.

“Netanyahu told me from now on he was going to force all his ministers to say whatever it was they wanted to tell him in just one minute,” Warshel said to laughter.

At a Stanford news conference, Levitt told reporters he too was surprised by the call notifying him of the award. (The scientists had been nominated for a number of years.)

“My phone never rings,” Levitt said. “Everyone sends me texts and email. So when the phone first rang, I was sure it was a wrong number. When it rang a second time, I picked it up. I immediately heard a Swedish accent and got very excited. It was like having five double espressos.”

A native of Pretoria, South Africa, Levitt has focused on theoretical, computer-aided analysis of protein, DNA and RNA molecules. He credited his wife, Rina, an artist, for supporting him. “I am a very passionate scientist, but passionate scientists often make very bad husbands,” he said.

At his home in Cambridge, Mass., Vienna native Karplus fielded telephone calls from well-wishers and the media early Wednesday as the family dog barked in the background.

He told a Harvard Gazette reporter that most callers wanted to know how he felt and how to explain his work in “simple terms.”

“If you like how a machine works, you take it apart,” he said. “We do that for molecules.”

Up until the 1970s, chemists relied on three-dimensional models of molecules -- Tinker Toy-looking assemblies of sticks and balls -- and the use of X-ray imaging to describe molecules and predict their interactions.

Even when scientists began using computer programs in the 1970s, lack of computer processing power forced them to focus on small molecules and to choose between classical or quantum theories.

The Nobel chemists however devised computer modeling programs that used both scales. By applying quantum calculations to the most chemically active portions of interacting molecules, and classical equations to less dynamic areas, they were able to calculate plausible reactions, which could then be tested in actual experiments.

Their methods are currently being used to optimize solar cells, catalysts for motor vehicles and drugs. Levitt in particular has written that he hopes to one day simulate a living organism on a molecular level.

ALSO:

3 U.S.-based scientists win Nobel in physiology or medicine

Nobel Prize in physics awarded to pair who theorized Higgs boson

Nobel Prize predictions: Higgs boson, exoplanets could yield winners