Nobel Prize in chemistry honors three scientists for their work on lithium-ion batteries

- Share via

STOCKHOLM — If you’re reading this on the screen of a cellphone, tablet or laptop computer, you can thank the newest winners of the Nobel Prize in chemistry for their work on lithium-ion batteries.

The batteries developed by the British, American and Japanese scientists did more than revolutionize on-the-go computing and calling. They also made it more feasible to store energy from renewable sources, opening a new front in the fight against global warming.

For the record:

9:39 p.m. Oct. 9, 2019An earlier version of this report referred to Akira Yoshino as Akira Yos.

“This is a highly charged story of tremendous potential,” quipped Olof Ramstrom of the Nobel Committee for Chemistry.

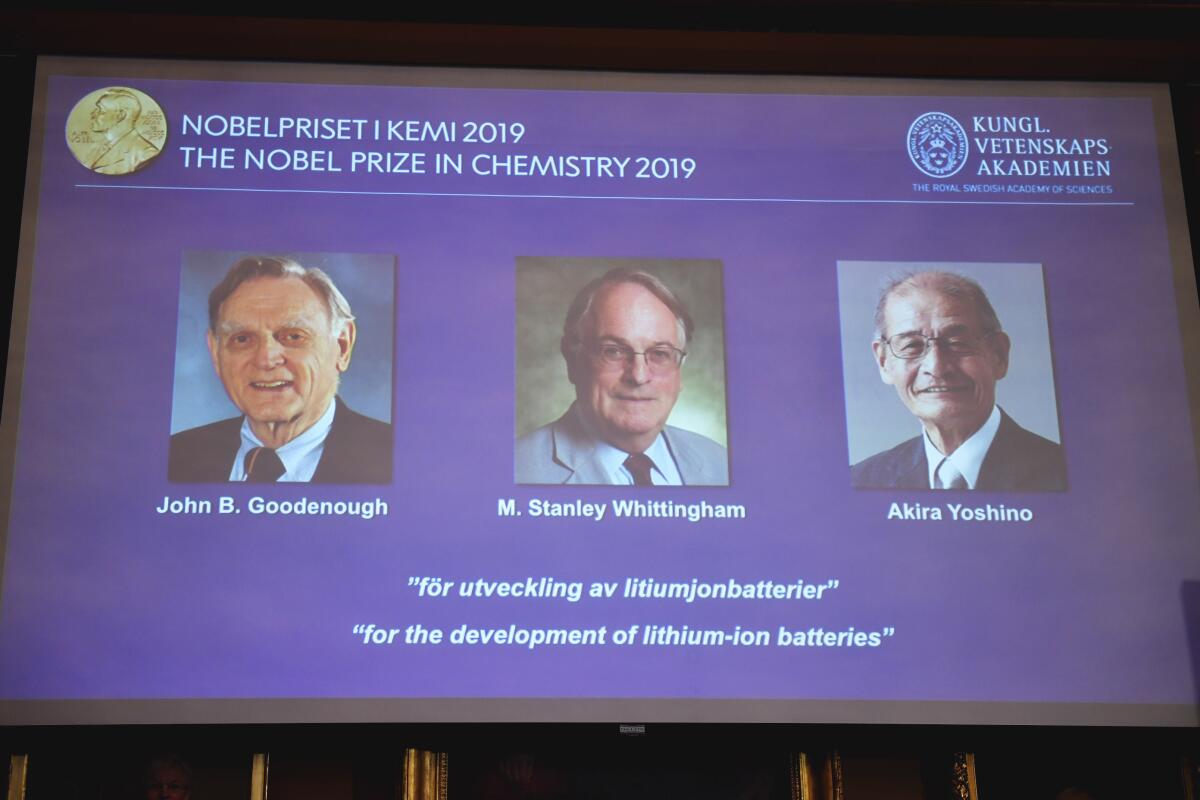

The prize announced Wednesday went to John B. Goodenough, 97, a German-born engineering professor at the University of Texas; M. Stanley Whittingham, 77, a British American chemistry professor at the State University of New York at Binghamton; and Japan’s Akira Yoshino, 71, of Asahi Kasei Corp. and Meijo University.

The three scientists were honored for a truly transformative technology that has permeated billions of lives across the planet, touching anyone who uses a cellphone, computer, pacemaker, electric car or any other device that is powered by a rechargeable battery.

“The heart of the phone is the rechargeable battery. The heart of the electric vehicle is the rechargeable battery. The success — and failure — of so many new technologies depends on the batteries,” said Alexej Jerschow, a chemist at New York University, whose research focuses on lithium-ion battery diagnostics.

Goodenough, who is considered an intellectual giant of solid state chemistry and physics, is the oldest person to win a Nobel Prize. He still works every day and said he is grateful he was not forced to retire at age 65.

“I’ve had an extra 33 years to keep working,” he said.

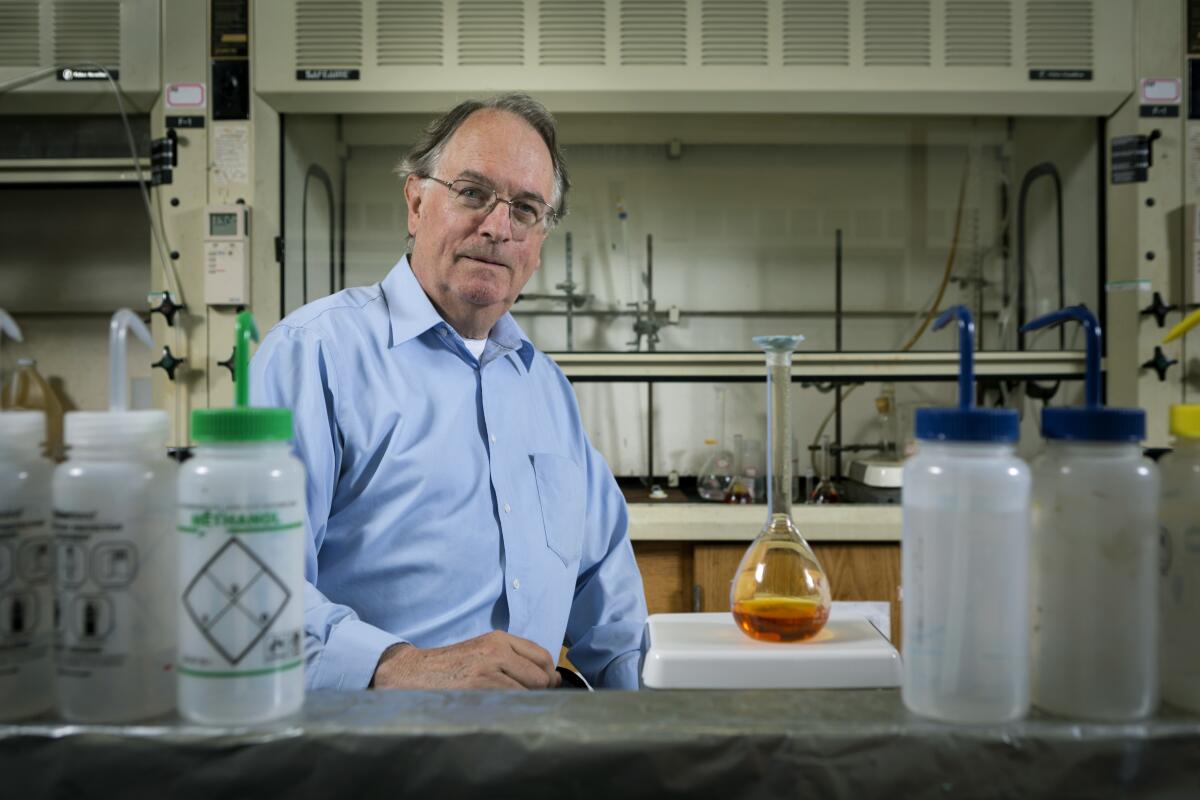

Whittingham expressed hope the Nobel spotlight could give new impetus to efforts to meet the world’s ravenous — and growing — demands for energy.

“I am overcome with gratitude at receiving this award, and I honestly have so many people to thank, I don’t know where to begin,” he said in a statement issued by his university. “It is my hope that this recognition will help to shine a much-needed light on the nation’s energy future.”

The three laureates each had unique breakthroughs that cumulatively laid the foundation for the development of a commercial rechargeable battery to replace the alkaline batteries containing lead, nickel or zinc that originated in the 19th century.

Lithium-ion batteries are the first truly portable and rechargeable batteries, and they took more than a decade to develop. Their invention drew upon the efforts of multiple scientists in the U.S., Japan and around the world.

The work had its roots in the oil crisis in the 1970s. Whittingham, who had studied superconductors at Stanford University, was hired by Exxon at a time when concerns about depleting oil reserves prompted the petroleum giant to invest in research in other fields of energy.

Exxon gave researchers like him “the freedom to do pretty much what they wanted as long as it did not involve petroleum,” the Nobel Committee said.

In his work, Whittingham harnessed the enormous tendency of lithium — the lightest metal — to give away its electrons to make a battery capable of generating just over two volts.

By 1980, Goodenough had built on Whittingham’s work and doubled the battery’s capacity to four volts by using cobalt oxide in the cathode. (The cathode and the anode are the two electrodes that make up the ends of a battery.)

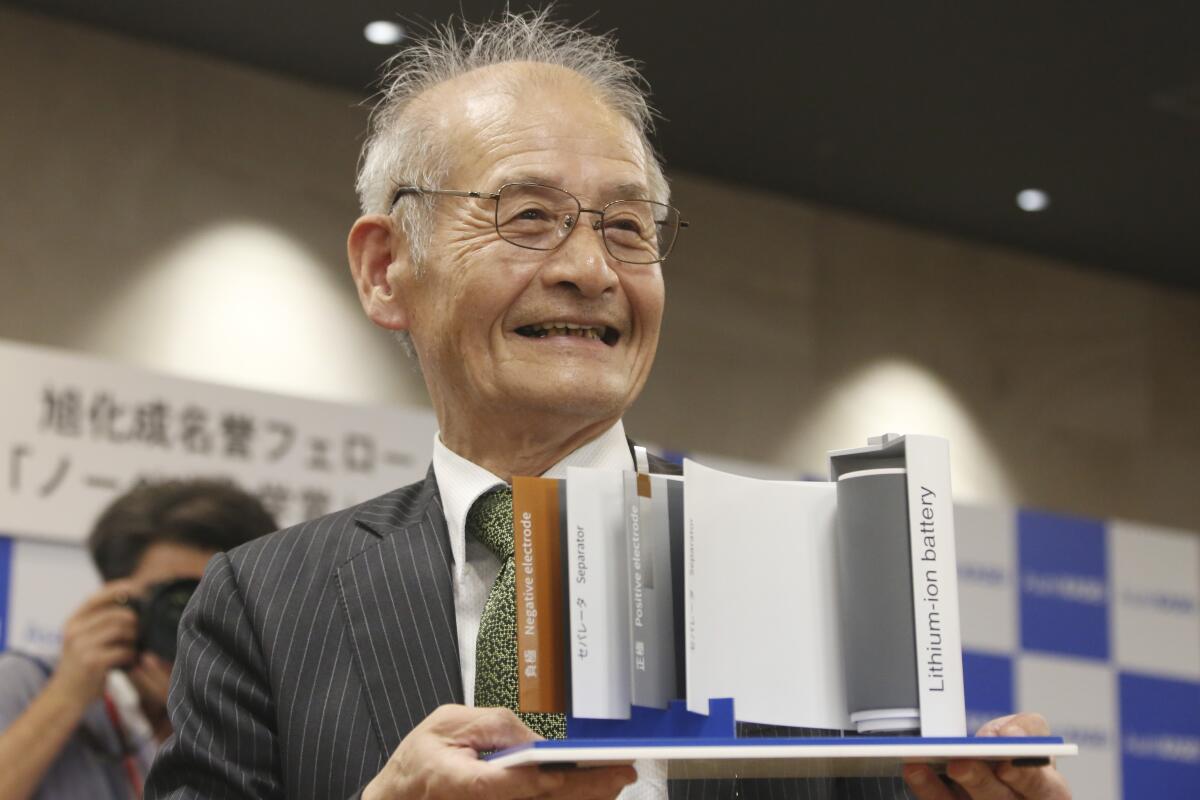

But that battery remained too explosive for general commercial use and needed to be tamed. That’s where Yoshino’s work in the 1980s came in. He eliminated the volatile pure lithium from the battery and instead opted for lithium ions that are safer.

Yoshino substituted petroleum coke, a carbon material, in the battery’s anode. This step paved the way for the first lightweight, safe, durable and rechargeable commercial batteries to enter the market in 1991.

“We have gained access to a technical revolution,” said Sara Snogerup Linse of the Nobel Committee, alluding to the environmental benefits of the discoveries. “The ability to store energy from renewable sources — the sun, the wind — opens up for sustainable energy consumption.”

Whittingham said he had no inkling that his work decades ago would have such a profound impact.

“We thought it would be nice and help in a few things, but never dreamed it would revolutionize electronics and everything else,” he said, calling the prize a “recognition for the whole field.”

“Hundreds of people have worked on lithium-ion batteries, and I think people felt that they were being overlooked,” he added. “We’re hoping this will push the field further and faster.”

The trio will share a $918,000 cash award. Their gold medals and diplomas will be conferred in Stockholm on Dec. 10, the anniversary of prize founder Alfred Nobel’s death in 1896.

Yoshino said he thought there might be a long wait before the Nobel Committee turned to his specialty — but he was wrong. When he broke the news to his wife, she was just as surprised as he was.

“I only spoke to her briefly and said, ‘I got it,’ and she [said] she was so surprised that her knees almost gave way,” he said.

The laureates said the field and its applications are still a work in progress, and they want to keep at it.

The batteries could have greater application in the ocean and space, Yoshino said, but further research and development are needed to adapt them to other gadgets and purposes. “Lithium-ion itself is still full of unknowns,” he said.

The prize turned out to be a bit of a family affair among the researchers: Yoshino said he visits Goodenough nearly every year in Texas.

“For him, I’m like his son,” the Japanese laureate said. “He takes very good care of me.”

Goodenough, in his own way, seemed to return the favor, telling reporters in London that in all of his 97 years: “What am I most proud of? I don’t know, I would say all my friends.”

On Tuesday, Canadian-born James Peebles won the physics prize for his theoretical discoveries in cosmology, along with Swiss scientists Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz, who were honored for finding a planet orbiting a star outside our solar system.

American Drs. William G. Kaelin Jr. and Gregg L. Semenza and Britain’s Peter J. Ratcliffe won the Nobel Prize for advances in physiology or medicine on Monday. They were cited for their discoveries of “how cells sense and adapt to oxygen availability.”

Two Nobel literature laureates are to be announced Thursday — one for 2018 and one for 2019 — because last year’s award was suspended after a sex abuse scandal rocked the Swedish Academy. The Nobel Peace Prize is Friday and the economics award will be announced Monday.