Nobel Prize in physics goes to three scientists for their work in understanding the cosmos

- Share via

STOCKHOLM — The Nobel Prize in physics was awarded to a Canadian American cosmologist who explored the evolution of the universe and to two Swiss stargazers who were the first to discover a planet orbiting a sun-like star outside our solar system.

Together, the work of James Peebles of Princeton University and Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz of the University of Geneva have changed scientists’ understanding of the universe and paved the way for answering that most fundamental of questions: Does life exist only on Earth?

“This year’s Nobel laureates in physics have painted a picture of the universe far stranger and more wonderful than we ever could have imagined,” said Ulf Danielsson of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, which selected the laureates. “Our view of our place in the universe will never be the same again.”

Peebles, hailed as one of the most influential cosmologists of his time, will collect half of the $918,000 cash award. Mayor, an astrophysicist, and Queloz, an astronomer who also works at the University of Cambridge in England, will share the other half.

The Nobel committee said Peebles’ theoretical framework about the cosmos — and its billions of galaxies and galaxy clusters — amounted to “the foundation of our modern understanding of the universe’s history, from the Big Bang to the present day.”

His work, which began in the mid-1960s, set the stage for a “transformation” of cosmology over the last half a century, using theoretical tools and calculations that helped interpret traces from the infancy of the universe, the committee said.

Among other things, he realized the importance of the cosmic microwave background radiation born of the Big Bang, a discovery that was honored with the Nobel Prize in physics in 1978. The theoretical tools he developed helped scientists come to understand that 95% of the universe is made of mysterious stuff called dark matter and dark energy.

A clearly delighted Peebles giggled repeatedly as he recalled how he answered a 5:30 a.m. phone call from Stockholm thinking that “it’s either something very wonderful or it’s something horrible.”

“I have a peaceful life,” said Peebles, 84, the Albert Einstein professor of science at Princeton. “It’s somehow now totally messed up!”

He added that he looked forward to traveling to the Swedish capital with his wife and children to accept the prize.

“I’ve always loved Bob Dylan. I can’t forgive him for not showing up to the scene of his Nobel Prize,” he said, referring to the singer-songwriter’s refusal to participate in the Nobel ceremonies after he won the literature prize in 2016. “It’s very disconcerting,” he said with a chuckle.

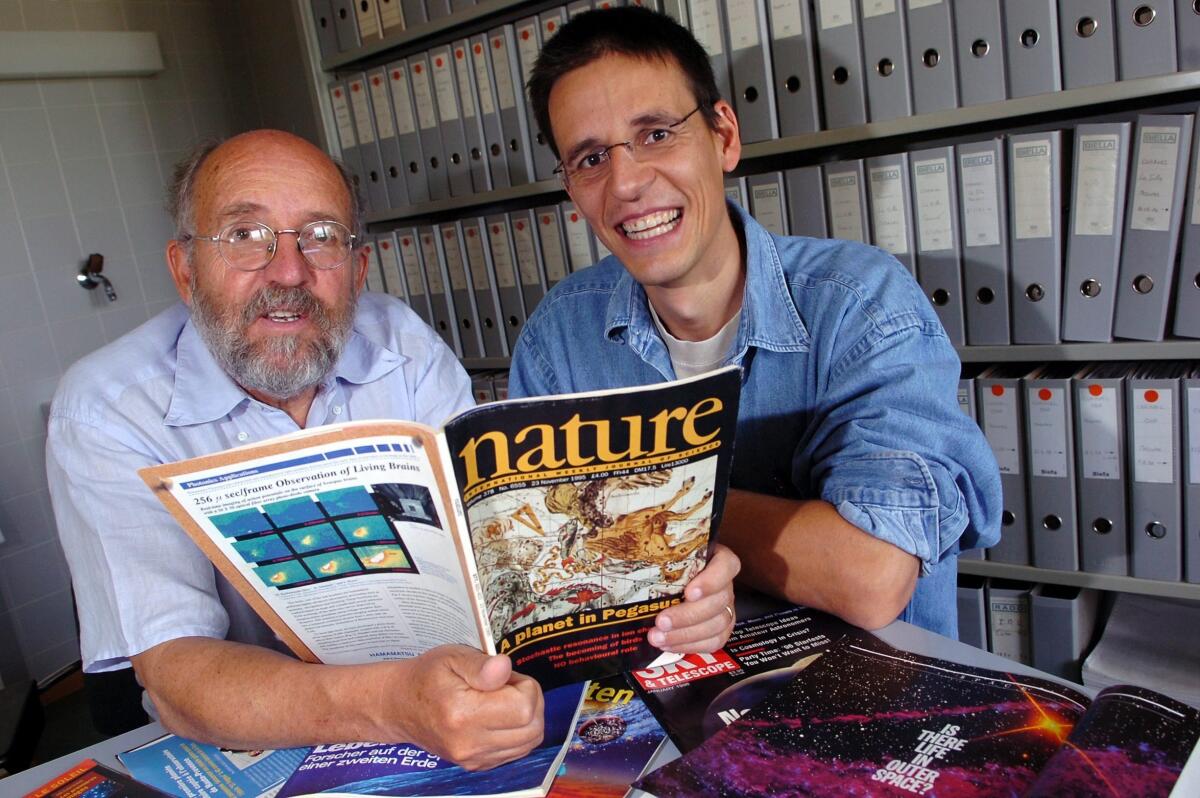

Mayor, 77, and Queloz, 53, were credited having “started a revolution in astronomy,” notably with the discovery of exoplanet 51 Pegasi B, a gaseous ball comparable with Jupiter, in 1995. An exoplanet is a planet outside the solar system.

At the time, “no one knew whether exoplanets existed or not,” Mayor recalled. “Prestigious astronomers had been searching for them for years, in vain!”

More than 4,000 exoplanets have since been found in the Milky Way since then, the Nobel committee said.

“Mayor and Queloz pioneered the path that will allow our generation to address one of the most exciting questions in science: Are we alone?” said Avi Loeb, chair of the astronomy department at Harvard University.

“We now know that about a quarter of all stars have a planet of Earth’s size and surface temperature, with the potential of hosting liquid water and the chemistry of life on its surface,” he said.

Queloz was meeting with other academics interested in finding new planets when the press office at Cambridge University interrupted to tell him of his win. At first, he thought it was joke.

“I could barely breathe,” Queloz said. “It’s enormous. It’s beyond usual emotions.”

Mayor said he learned of his win “by chance” when he logged onto his computer after leaving the hotel where he had been staying in San Sebastian, in northern Spain. Though he knew he had been nominated several times before, the Swiss professor said he was “absolutely not expecting this.”

The award follows “a long, long period of work, with colleagues. It’s a huge honor,” he said after arriving in Madrid, where he was to speak at scientific events this week.

Swedish academy member Mats Larsson said this year’s was “one of the easiest physics prizes for a long time to explain.”

“If there are a hundred billion planetary systems, with maybe 10 billion planetary systems with Earth-like planets, it would be highly unlikely and against all physical theories to assume that life only developed on our planet,” he added.

The cash prize comes with a gold medal and a diploma that are received at an elegant ceremony in Stockholm on Dec. 10, the anniversary of the death of prize founder Alfred Nobel in 1896.

On Monday, Americans William G. Kaelin Jr. and Gregg L. Semenza and Britain’s Peter J. Ratcliffe won the Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine, for discovering details of how the body’s cells sense and react to low oxygen levels, providing a foothold for developing new treatments for anemia, cancer and other diseases.

The Nobel Prize in chemistry will be announced Wednesday, two literature prizes will be awarded Thursday, and the peace prize comes Friday. This year will see two literature prizes handed out because the one last year was suspended after a scandal rocked the Swedish academy.