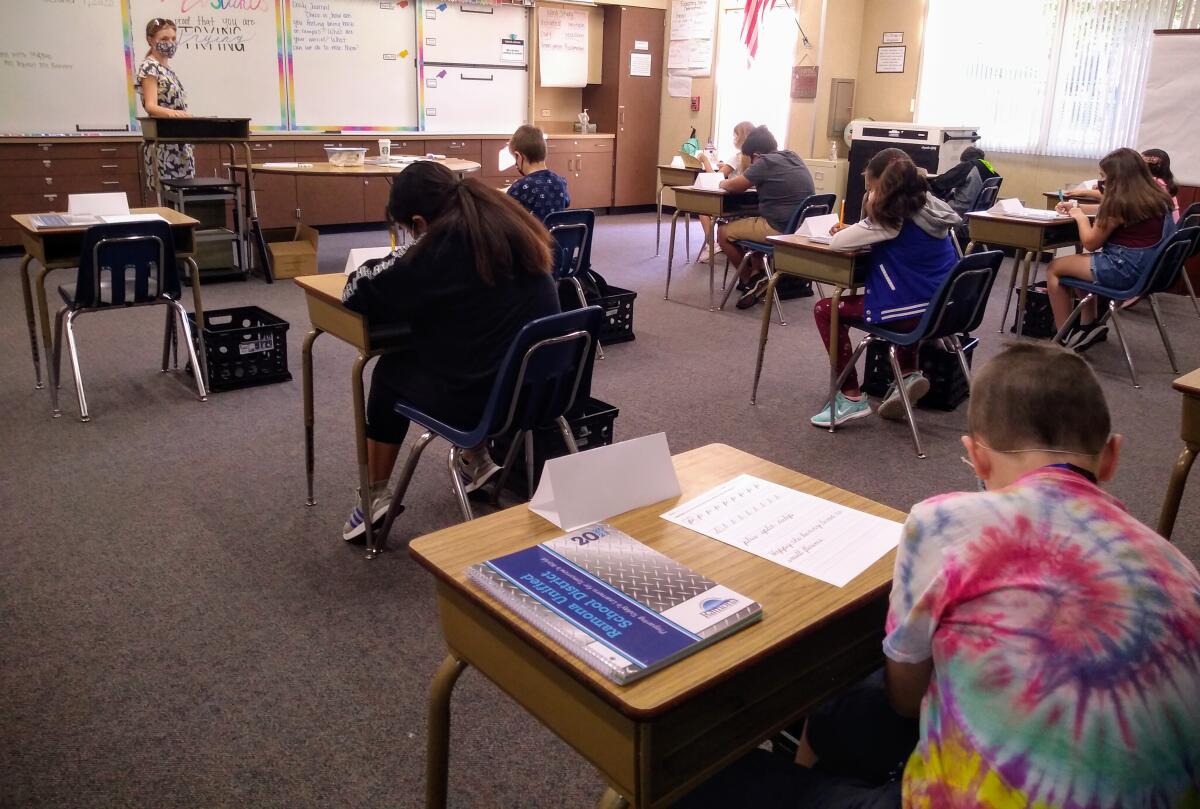

No vaccines for young children, but schools can reopen safely in the fall, a study shows

- Share via

The masks, the social distancing, the stick-up-the-nose testing: Those unpleasant coronavirus-controlling measures are far from over for K-12 kids returning to in-school learning after summer vacation ends.

It’s unlikely that a COVID-19 vaccine will be available for children under 12 before classes resume in the fall. But a new study has found that when elementary-school children mask up and maintain some distance from one another over the course of the school day, a single infected child will likely pass the infection to fewer than one other student, on average, over the course of 30 days.

But if schools ditch the masks, abandon efforts to reduce mixing among children, and fail to detect and isolate those who may be infected, outbreaks can certainly happen, a modeling exercise shows.

Those outbreaks won’t necessarily be large, however, and that leaves local school boards and mayors with difficult choices.

If they are unwilling to accept the infection of relatively small numbers of students, they may have to consider adopting some potentially unpopular measures, including hybrid attendance/online learning, strict isolation measures for the classmates of infected students, and the ongoing use of face coverings.

Over the course of 2,000 runs of their model elementary school with a relaxed approach to masking, social distancing and isolation, a single infected child was likely to spread the coronavirus to an average of 1.7 other children over 30 days, researchers found.

That may sound like a strong case for dropping the most onerous public health measures in elementary schools. But it doesn’t take into account the substantial element of randomness the model revealed. About 8% of the time, five or more children went on to become infected by a single infected student over 30 days.

That’s still a small outbreak, with a relatively small probability. But it could feel very real to the families involved.

A high school yearbook like no other: Teens work tirelessly to chronicle a year of pain, resilience

And in high schools that return to in-class instruction, the risks are even greater when measures to reduce coronavirus transmission are scant. That is largely because older adolescents appear to spread and get sick from the coronavirus at rates closer to those of adults than to younger children.

With students on campus five days a week and relaxed social distancing and masking measures in place, an outbreak seeded by a single high school student could touch off 23 to 75 additional infections among fellow students, employees or classmates’ families over the course of a month. Weekly testing could drive down that number of downstream infections to five in the same period.

Importantly, the model did not consider the effect of vaccinations among those ages 12 to 17. The COVID-19 vaccine made by Pfizer and BioNTech has been authorized for use in 16- and 17-year-olds since December and for those ages 12 to 15 since May.

The new findings were published Monday in the Annals of Internal Medicine. They emerged from a detailed “agent-based” computer model, in which virtual individuals in a population of students, school employees and students’ families interact under defined rules that dictate the behavior and infectiousness of each.

Such models capture the range of outcomes that emerges when a diverse population of people interact under different sets of rules. So they’re particularly useful for weighing the relative effectiveness of policy measures that would change how people interact.

To estimate how in-person instruction would play out under different rules of engagement, researchers from University of Maryland and Harvard’s School of Public Health created a model of an elementary school with 638 children from 432 households and 30 teachers and administrators attending its pupils.

High schools were bigger and students’ movements were more complex. In that model, a total of 1,451 students from 1,223 families rotated through eight classrooms daily. Some 63 teachers taught these students, and congregated in staff rooms as well. And another 60 school employees intermingled with students in and out of classrooms.

A range of classroom arrangements were tried out: full-time, in-person attendance by all; the in-school organization of students into “cohorts” with limited interactions beyond; cutting class size in half (and doubling the number of teachers); and having half of students come to campus two days a week, with the other half attending in person another two days and everyone working online three days a week.

Researchers simulated these scenarios thousands of times under different scenarios: with high, medium or low “mitigation” measures in place, with and without testing for asymptomatic infections, and with varying levels of isolation for students who test positive and their exposed classmates.

Schools race to reopen, but a small school district in Pico Rivera — where families suffered heavy pandemic losses — is not among them.

The findings reinforce that the risks of bringing students back to campus are small while the benefits are large, Dr. Ted Long, executive director of New York City’s COVID-19 Test & Trace Corps, wrote in an editorial that accompanied the study.

“The evidence is now compelling: our schools can reopen safely,” Long wrote, noting that roughly 40% of U.S. schoolchildren have not been invited back to the classroom since the pandemic shuttered schools across the nation.

“If schools can reopen for in-person learning, then they must,” he added, “to avert the mental health and educational crisis that is at our doorstep.”

The study comes as COVID-19 among school-age children has become the focus of growing concern.

A new report issued by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention makes clear that COVID-19 hospitalization rates among adolescents are almost three times higher than the number hospitalized with flu in a typical flu season. What’s more, just over 31% of adolescents ages 12 to 17 who were hospitalized for COVID-19 this spring had to be admitted to the intensive care unit, and close to 5% required mechanical ventilation.

CDC Director Dr. Rochelle Walensky called the numbers deeply concerning.

The report’s findings “reinforce the importance of continued COVID-19 prevention measures among adolescents, including vaccination and correct and consistent wearing of masks,” the authors wrote.

Meanwhile, a surge of COVID-19 illness and deaths among Brazilian children and adolescents has raised concerns that the Gamma variant, a version of coronavirus first detected and now widely circulating in Brazil, may affect children more severely than other strains.

The Gamma variant accounted for 7% of the coronavirus samples that had been genetically sequenced in the United States in the two weeks ending May 8, and it has been linked to higher rates of transmission and some ability to escape the effects of COVID-19 treatments.