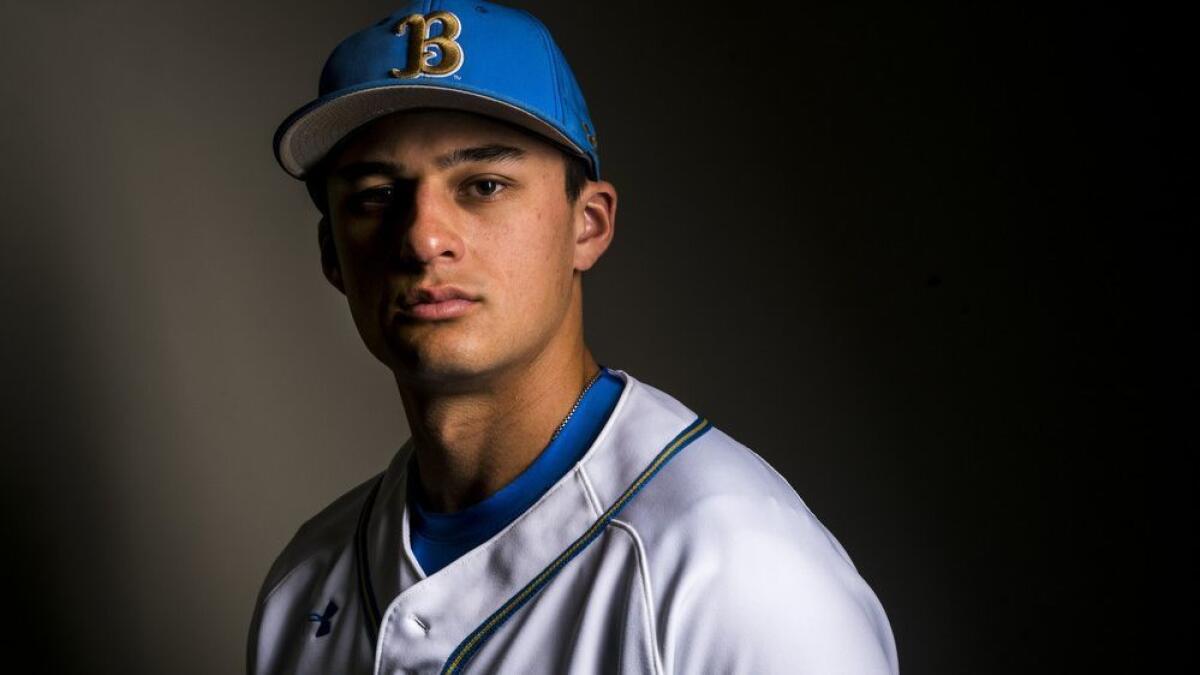

UCLA’s Chase Strumpf uses a steady approach to become one of the nation’s best players

- Share via

To Niko Gallego, UCLA baseball’s volunteer assistant coach, the compliments seemed ceaseless. “Nice play,” he’d say. “Nice play. Before you know it, you’re just kind of numb to saying ‘nice play’ to the guy.”

There was the practice last year when Bruins second baseman Chase Strumpf seemed to grab every ground ball hit his way and nail each throw to first base. There was the 11-game multi-hit streak and a 32-game streak of reaching base last season. Somewhere along the way, Gallego hatched a nickname — “Steady Strumpf.”

“He’s more of like a silent killer,” junior infielder Ryan Kreidler said. “He’s not a huge energy guy, but at the end of the day, if the ball’s hit to him, or if he’s at the plate, you trust him.”

As the Bruins, a consensus top-five team in the national rankings, open their season Friday with a home series against St. Johns, Strumpf has emerged as a top major league prospect. The junior, a unanimous first-team preseason All-American, is the No. 23 college prospect for the major league draft in June, according to D1Baseball.

Strumpf’s nickname applies to his play and his mood. He does not shout at his successes or grow sullen after mistakes. In the dugout, he cracks jokes with Kreidler and approaches high-pressure moments by remaining quietly confident. Steady.

Strump knows where that steadiness comes from: Ken Ravizza.

A noted sports psychologist who worked with several major league and college teams, Ravizza began helping out at UCLA in 2010.

He spoke with the Bruins at team meetings and on Thursdays in the clubhouse before each weekend series. Sometimes, he joined them in the dugout during games; when adversity emerged, he would say, “beautiful.” He sat by the bat box with a miniature toilet and a small brown stuffed monkey, tools for players to flush their mistakes and physically pull a monkey off their back, which Strumpf eyed as reminders while preparing to hit.

“I’m gonna cherish that and carry that through my game forever,” Strumpf said of Ravizza’s teachings.

Since he was young, Strumpf has sought to not overthink baseball. When teammates on his travel team worked with private hitting coaches at 7 and 8 years old, Strumpf developed his form in the batting cages at a local park with his father, early on Sunday mornings after a bacon, egg and cheese bagel for breakfast.

“I always told myself, you know, don’t think,” Strumpf said. “Just go play. Don’t think about things.”

For that reason, Strumpf was skeptical about relying on the team’s mental coach his freshman year at UCLA. Besides, he was known for being collected in high school. The most emotion his coach at JSerra High, Brett Kay, saw from Strumpf was during the first round of the Southern Section Division I playoffs in 2016, when Strumpf stretched an 0-and-2 count on a two-out at-bat to 13 or 14 pitches, then hit a game-winning, three-run home run. Strumpf reacted with a hop.

“You don’t see much elevation out of him,” Kay said, adding: “He’s Mr. Cool. … He lets his play do the talking.”

Strumpf committed to UCLA before playing a high school game and spent all but one of his summers playing for JSerra’s summer league team. He did not go to showcases, and his father declined any attention offered from scouts at high school games. There was no need to prove himself.

At UCLA, Strumpf started 54 games as a freshman, but his successes came in spurts. He hit a home run against USC at Dodger Stadium, crushed UCLA’s first grand slam in two years and drove in seven runs in one game. But he committed five errors, struck out multiple times in 10 games and went six straight games without a hit.

He struggled to get past his failures at the plate; they stirred in his head in later at-bats and sometimes when he was playing defense, spiraling into more missteps. In the months before his sophomore season, Ravizza’s words began to resonate.

Ravizza spoke about the mental state before an at-bat like it was a traffic light. The goal was green, calm and confident, but Strumpf realized he sometimes approached the batter’s box mentally yellow or red, doubting himself, overthinking.

He began buying into Ravizza’s message. If his mental state lagged in games, he sought Ravizza. “Hey, Ken,” he’d say. “I’m not in the right spot right now. I need to get myself back on track. What should I do?”

Sign up for our daily sports newsletter »

Through Ravizza, Strumpf learned to recognize mental obstacles and gained techniques to move past them. On defense, he honed his focus during each pitch then let his mind wander in between them, a method Ravizza called stepping in and out of “the circle.” He used breathing to stay composed at the plate, as Ravizza implored him to focus only on the next pitch.

“I kind of realized that well, it’s not exactly just overthinking the game,” Strumpf said of mental coaching, “it’s kind of just, you know, being aware of where you are as a player and where your mind-set is. … Over time it kind of just becomes second nature.”

In Strumpf’s sophomore year, his on-base percentage jumped from .315 to .475, his extra-base hits from 16 to 36. After hitting .239 as a freshman, Strumpf batted .363 as a sophomore, with 59 runs and 53 RBIs in 58 games. He committed just two errors and earned second-team All-America honors.

“I learned a lot from him just listening,” Strumpf said of Ravizza. “I think what he gave to us was more than enough, and I’ll always cherish all the things I learned from him.”

Ravizza died of a heart attack in July 2018. He was 70.

“It was very, very tragic for all of us,” Bruins coach John Savage said. “He meant so much to us personally, he meant so much to us, you know, just in terms of our team growth. He helped the coaches as much as the players.”

Along with the rest of UCLA’s upperclassmen, Strumpf has tried to pass Ravizza’s lessons to the freshmen. They shared their own memories of Ravizza and gave younger players copies of his book: “Heads-Up Baseball: Playing the Game One Pitch at a Time,” which Ravizza gave the Bruins in Strumpf’s freshman year.

“Ken’s message is deeply rooted in our program,” Gallego said. “And pretty much everything that we talk about, in some sort of facet, can be related back to Ken Ravizza’s teachings.”

Ravizza’s philosophies persist in Strumpf’s routine as he readies himself for the next pitch. After a bad swing, he steps outside the batter’s box and stares at the left foul pole, aligning himself in the moment, a technique taught by Ravizza. Before every pitch he stares at the ‘A’ in the “Alpha” logo at the center of his bat, as he fills his lungs with a long breath.

Once the lines of the letter become clear, he lifts his eyes, ready to swing.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.