A modern relic: 1932 hacienda updated in Santa Monica

- Share via

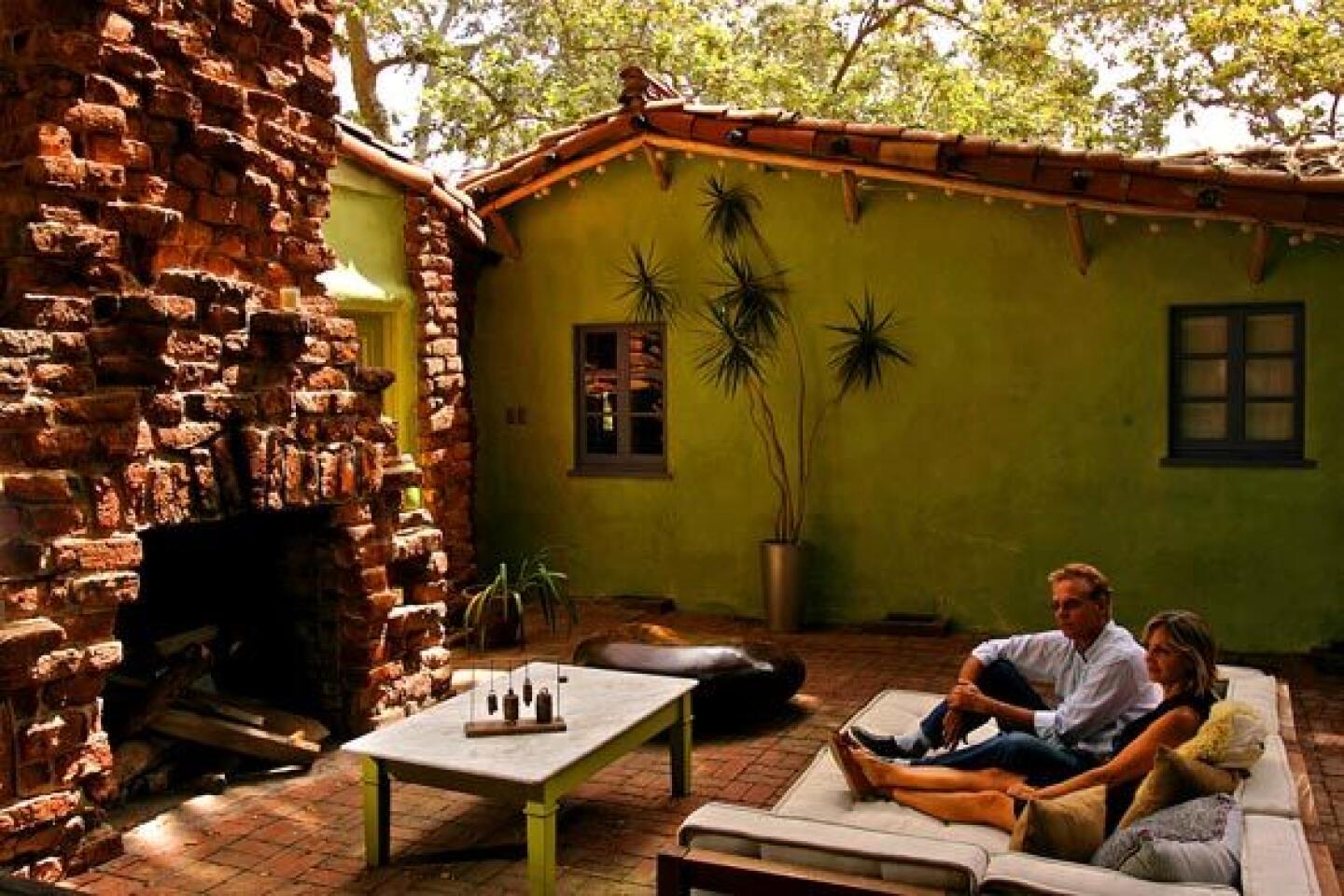

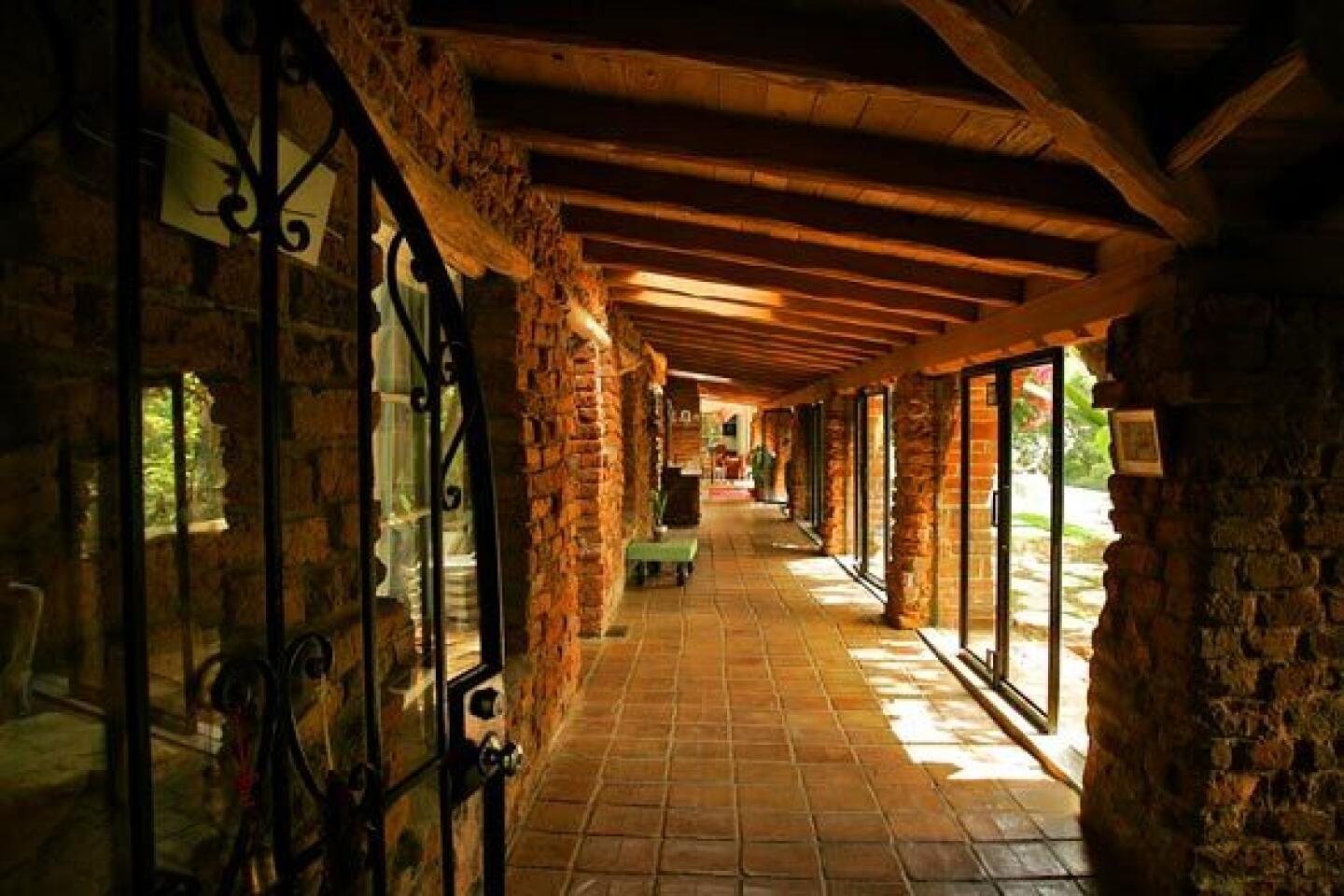

THERE IS no state-of-the-art media room, no marble spa bathroom, nor some of the other luxuries one might expect at the home of “High School Musical” creator Bill Borden and modern architect Melinda Gray. Their Santa Monica house is a simple ranch, a 100-foot-long rectangle fronted by a loggia, its seven archways formed of fat bricks salvaged from an old kiln. “Our kids go to the same school as Jamie Lee Curtis’, and when she came over, she said, ‘You’re like hippies who made enough money to buy a big house,’ ” Borden says. “It’s just not a fancy house.”

The once-ramshackle hacienda was built by a Swedish boat builder in 1932 for Leo Carrillo, the cowboy movie star best known as Pancho, sidekick to TV’s Cisco Kid. Lesser folk might have restored the fanciful structure as a period piece or just torn it down, but those options were anathema to self-proclaimed “complete modernists” Borden and Gray, who instead applied their contemporary design sensibility while preserving the integrity of the vernacular architecture.

As the producer who launched the MTV musical “The American Mall” this week and the creative force behind Gray Matter Architecture, the couple didn’t lack for resources or imagination. Nonetheless, it was a challenge reconciling what the house had been and what they wanted it to become.

“When we first bought it, one side of me secretly hoped an earthquake would bring the house down,” Gray says with a laugh.

“With every change I have had to ask myself, what will I do here that makes the most sense while trying to be honest about how it was in the beginning?”

With thick adobe walls, low tile roof and long eaves that make air-conditioning unnecessary, the house was green for its time. But it also had been cast into shadow by mature oaks and nearby mountains. “I couldn’t even read a book in the daytime,” Gray says. “It really needed natural light.”

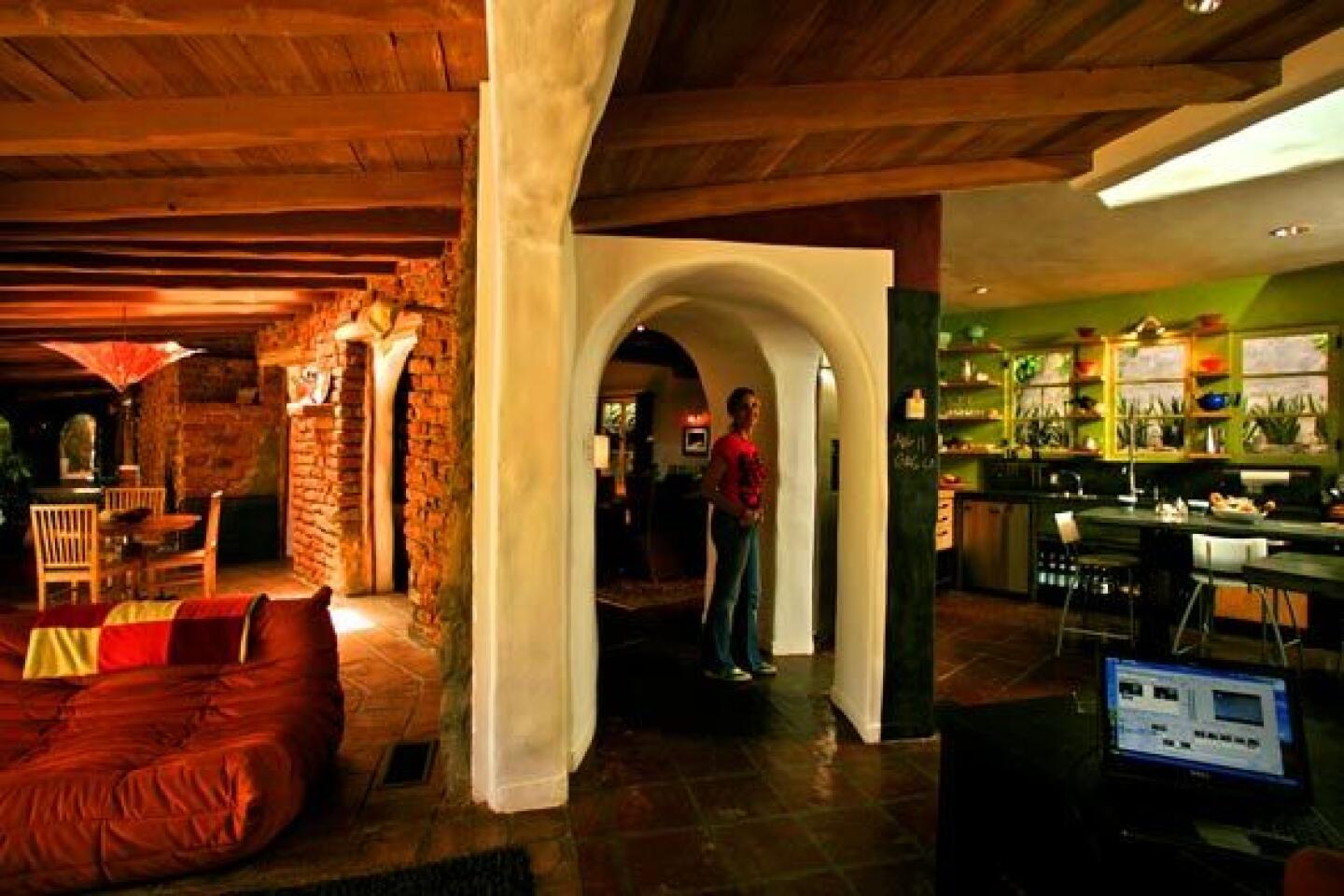

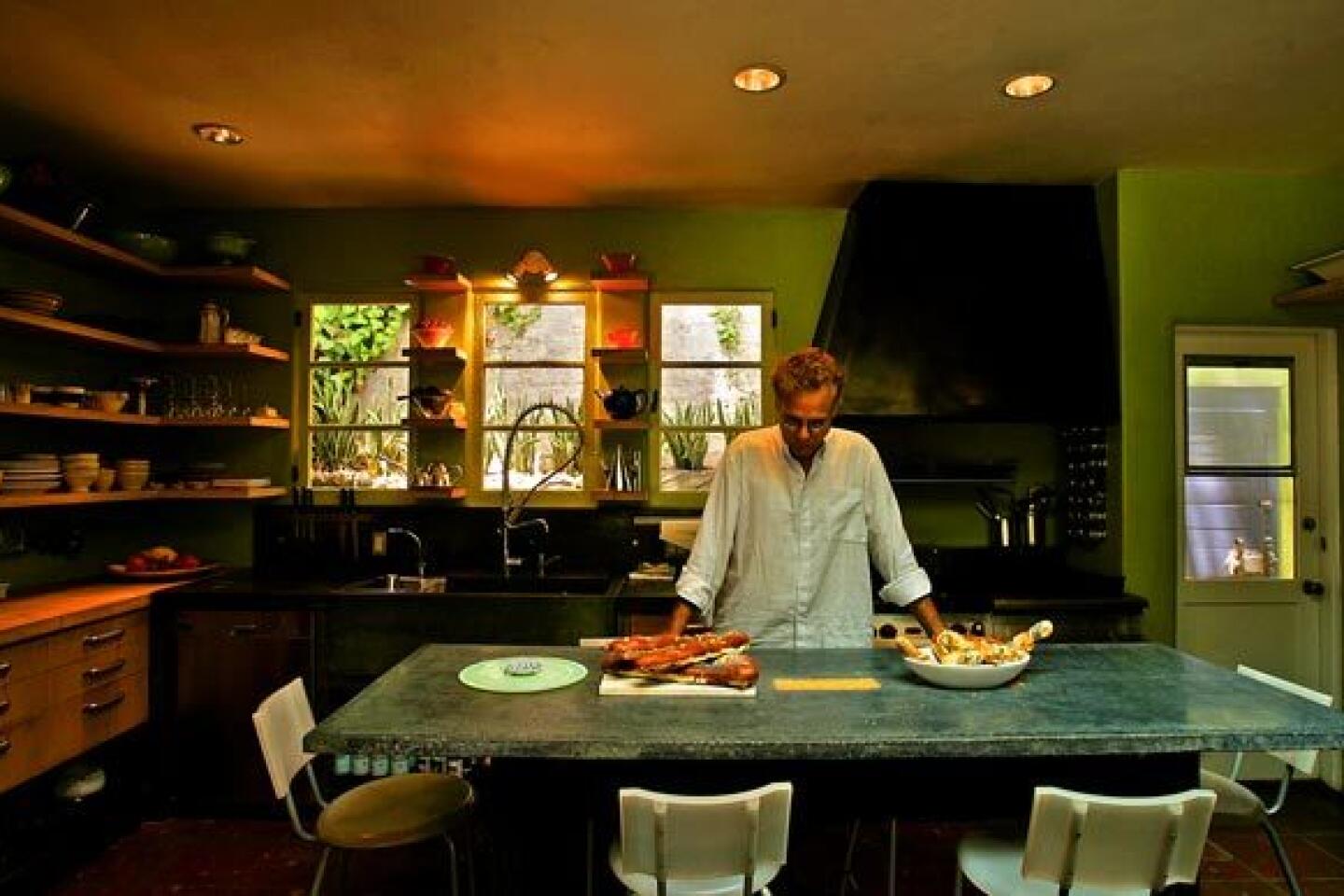

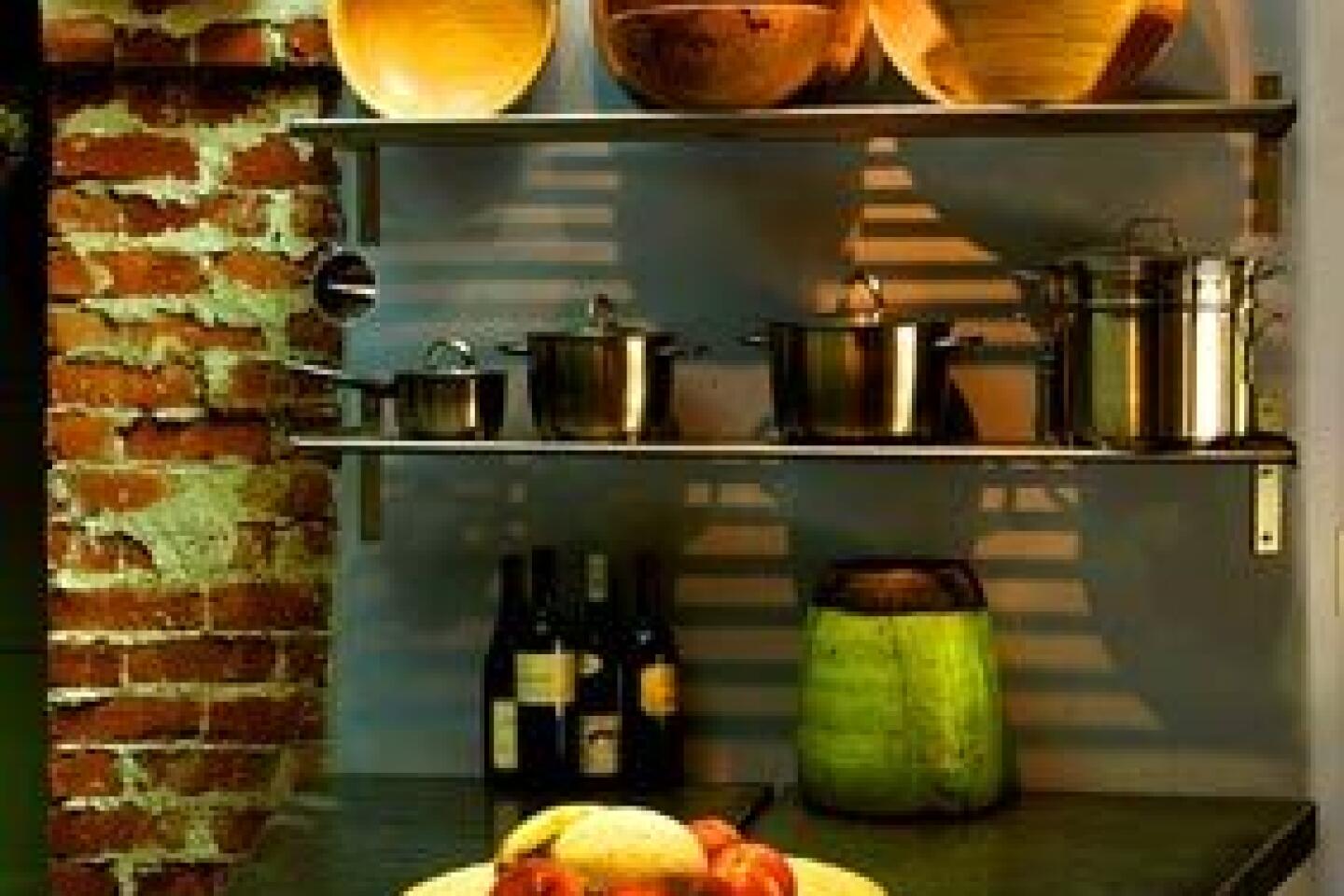

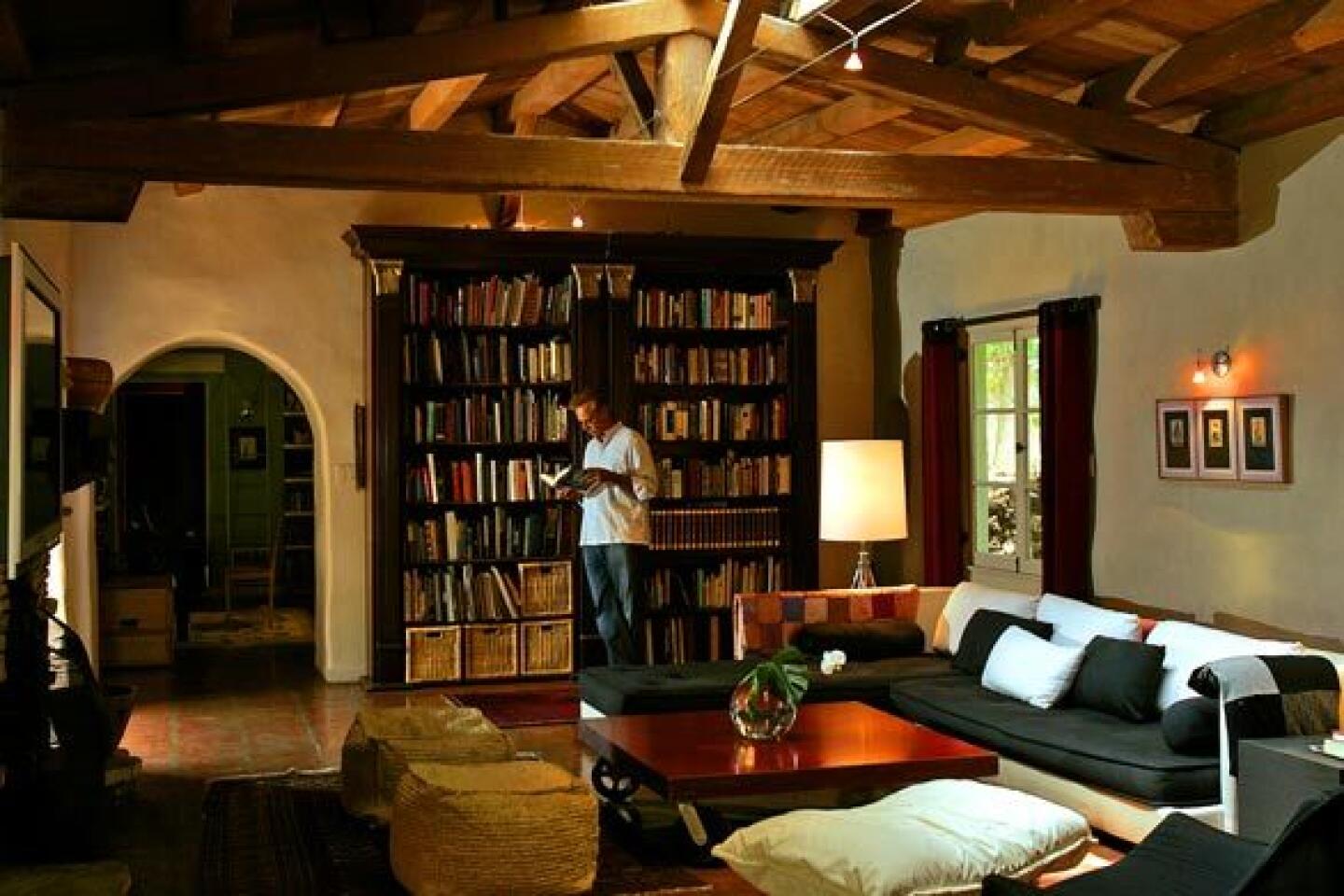

She installed a skylight that floods the living room with sunshine, illuminating wooden trusses and beams. The kitchen, closed off and claustrophobic, became more airy once a wall was removed and another skylight added. New open shelving, poured concrete islands and an unrestricted flow into the adjacent work space and lounge created a great room with a Spanish accent.

In the loggia, Gray hired retail storefront glaziers to painstakingly fit glass into the brick arches. For the larger openings, she designed steel walkout doors and a 10-by-6 1/2 -foot window on a sliding track.

“Weather-stripping it was the trickiest part,” Gray says. “But we live in California. So what if a little fresh air sneaks in?”

That is the allure, Borden says. “I like the style of living outdoors and being connected to nature, that any moment you can be anywhere in the house and just step outside,” he says.

The newly enclosed loggia not only brought in light and ventilation but also provided a much-needed hall for the house, which is laid out like a railroad flat. At 7 feet wide, the loggia also allowed the couple to create multiple seating areas in a space where Carrillo’s wooden saddle hooks are still lodged in the wall.

At one end of the loggia lies a meditation nook. In the center, a Biedermeier dining table and Swedish country chairs sit under a fanciful umbrella light reminiscent of a Fortuny lamp. Nearby, a daybed looks out to the new pool Gray designed.

Larger pieces of furniture proved problematic because of the low ceiling and the way the floor, once outdoors, slopes for drainage.

“Things that sit on the ground, without legs, seemed to be more forgiving,” Gray says, pointing out a pair of vibrant orange, floor-hugging Togo love seats by Ligne Roset.

She may be the detail-driven innovator, fitting rectangular doors into arches, constructing massive barn doors on sliding tracks and painting faux grout lines on poured concrete floors to give them the appearance of pavers. But her husband comes with his own set of design skills. With their three sons, the couple built furniture from laminated plywood and leftover doors recycled from film sets.

For both, updating the house has provided more than an opportunity to fool around with unusual materials. Though she has no intention of shifting her style to adobe modern, Gray admits that the process has influenced her work, particularly in how she orients a home on its site. For Borden, home is now a rustic relic transformed into a contemporary indoor-outdoor space.

“The house combines the modern and the 1930s and still works,” Borden says. “Melinda has honored the tradition by introducing it to her architectural language.”

The other night, when Borden was sitting on the daybed Gray designed and he built, the sliding door open to the cool air, the analogy hit him: The sheet of glass was like what one would see at a contemporary museum.

“A modern display case showing off an old piece of work,” he says, “in a whole new context.”

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.