All the essential elements

- Share via

NEAR the crest of a hill overlooking the Pacific sits a small, sublime architectural adventure. Its boxy exterior, a windowless facade of steel and stucco, seems to recede into the landscape. But surprises start at the massive front door — an 8-by-9-foot stainless steel slab that opens electronically, like a bank vault.

Inside, floors of inky, blue-tinged steel, set like stone in 2-by-6-foot plates, meet walls of oiled hemlock. An entire ocean-facing wall of glass disappears when its panels fold up to the ceiling. And then there’s the master bedroom, which also functions as the master bath, its focal point a glow-in-the-night tub that is a hand-cast resin sculpture. The house is profoundly personal, the shared minimalist vision of landscape architects Abbie and Bill Burton and their architect Jennifer Luce, who won two American Institute of Architects awards for it in May.It’s the kind of house to experience, rather than just visit. The unusual blend of industrial and natural textures both soothes and startles. Luce manipulates light and space in ways that challenge convention and delight the senses.

“What we’re passionate about, along with Jennifer, is design from the essential elements. The raw character of the material is in full view, in its natural form, not covered by anything else,” Bill Burton says.

In Luce, 47, Canadian-born with a Harvard design degree, the couple found an artist who heeded the spirit, not just the specifics, of what they wanted.

The Burtons, who live with their two teenagers and a Bernese mountain dog, bought the 1970s, two-story house seven years ago. “It looked frightening at first,” Bill Burton says. “Really odd big bedrooms, black walls, mirrors everywhere.” But the couple agreed on the home’s potential. “It had a great ocean view, great basic form. The flat-roof shell was what we were attracted to. And we loved the upside-downness of it.”

Two large bedrooms were on the ground floor. The kitchen, living, dining and master bedroom areas were upstairs, where the entire back of the house overlooks the ocean.

Burton says the bedrooms were too big, the public spaces too small, the ocean view minimized by traditional doors and windows. The kitchen was awful for a couple who loves to cook. “It was fit for a small apartment.”

The couple wanted the house totally closed in front, where it faces the street, and totally open to the view in back. They asked Luce to remain within the original footprint (2,800 square feet, including the garage), and to downsize the private rooms equally. “Everybody’s private space would take a hit,” Burton says. “We would increase the public spaces, which is where we really live.”

Luce — who has owned her San Diego firm, Luce et Studio, for 15 years — first designed the Burtons’ new Solana Beach offices. Then she started on their house, which was torn down to its wood studs for the renovation.

It is now so different in every way from the original that AIA judges said they were “shocked that it was a remodel.” The Burtons did keep a central skylight as a “kind of homage” to the old house. Luce turned that into what looks like an art installation by covering it at ceiling height with light-diffusing industrial fabric the same color as the ceiling. It’s an idea she came upon in her design for Nissan’s automotive design studios in Farmington Hills, Mich., which won three AIA awards in May.

“Her skylight in the Burton house looks like a Robert Irwin scrim,” says Santa Monica architect Lawrence Scarpa, a judge in the San Diego AIA contest. “The details in that house are terrific, especially the doors. Tall doors, skinny doors, concealed doors. All the doors feel like sculpture. Very three-dimensional and spatial. Opening them is like opening jewel boxes.”And then there are those blue-tinged steel floors. The Burtons say they got the idea on a visit to a 50-year-old Wonder Bread bakery in San Diego, where they loved the look of the steel floor, including the marbled patina that occurs over time (which some might call rust).

“We liked that look, but when the steel plates came to the house, they were hot-rolled steel, so they have a sort of blue quality. We love the blue, so now we’re going about the process of finding ways to protect and keep the color the way it is,” Burton says.

Luce commissioned the steel plates from one of many different metal craftspeople with whom she regularly works. The result is a floor that almost calls out to be touched. Slip off a sandal on a torrid day, and steel caresses the sole with its cool, soft, satiny surface. (Yes, we know steel is hard. But it doesn’t feel that way. Burton describes it as “comforting.”)

Says Scarpa, “The irony is that people think of steel as cold and industrial. In many ways it’s very warm. When it weathers, it’s like an old villa, it takes on a patina and a life of its own.”

Steel is used in many ways throughout the house. Entering, what you first see is the profile of a sculptural black steel staircase with what appears to be a vast solid wall of hemlock behind it. The wall isn’t solid at all. It contains invisible doors that camouflage entries to closets, a powder room and the two teenagers’ rooms on the other side of the wall, which each have a bath and garden view.

Looking up to the second floor from the entry, off to one side you see a black steel cantilever, a steel-supported floor that Luce designed to become the dining room.

The stairway leads up to the heart of the house — the commercially rated kitchen. It forms the center of what is essentially one large open living, dining and cooking area, all with an ocean view. Because the Burtons are avid cooks, Luce says, they wanted the kitchen as part of the main living space, rather than off by itself. “It occupies probably the largest square footage devoted to any one function in the house,” she says.

Burton calls the kitchen “ground zero of the house. We live around it, because that’s how we... like to live. We cook, we talk, that’s what we do.”

The kitchen has a noncombustible steel wall, a floor of industrial rubber and is filled with restaurant equipment: a commercial hood with its own fire-suppression system and air exhaust and intake systems. Two commercial ovens are topped with oversize burners, and hot tops that are a special point of pride for Burton. “They’re not griddles,” he says, of the hot tops. “They’re for slow cooking sauces or stocks.”

Most important, he says, “is the level of gas output you get from commercial equipment. A Viking range will have about 11,000 BTUs of gas. This has about 35,000 BTUs. So you can really get a nice caramelized finish on things.”

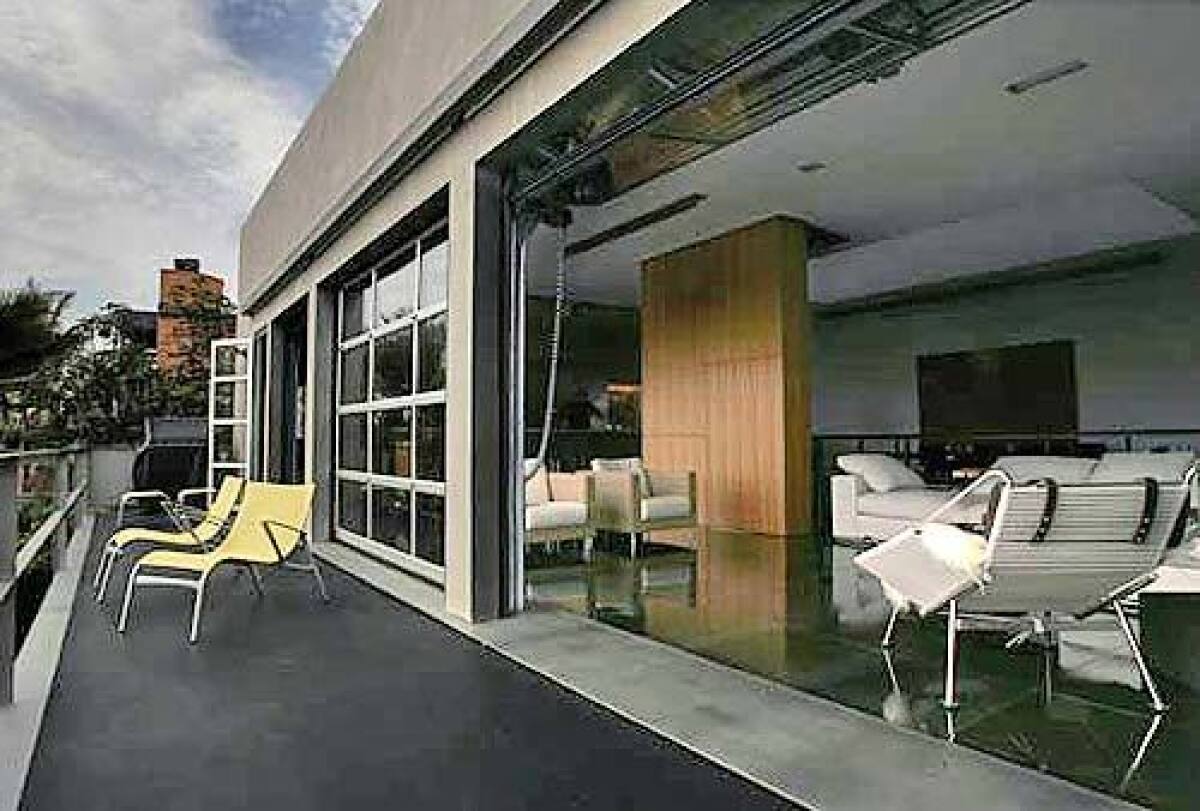

By far the most dramatic windows (or perhaps they are doors) in the house form the living room wall that faces the ocean.

Electronically controlled, they fold up into themselves to literally obliterate the division between inside and out. Luce says she discovered the doors in use at firehouses in the United Kingdom, which is where she had them made.

“The whole back wing of the house opens up the important part is that they bi-fold, stack up on themselves, unlike rolling garage doors that dominate the ceiling,” Burton says. “The motor controls and the motors and the whole support structure for them is all in the room. It’s a fascinating thing to watch. Push a button and it’s a machine sound and they go clunk-clunk. They are aluminum and glass.”

In fact all windows and doors in the house have been stunningly reproportioned by Luce, who sees special significance in these “areas of transition,” where one experience ends and another begins. The windows all have horizontal aluminum mullions that create what she describes as “a visually soothing effect.”

Of course, by making the home’s social spaces larger, it “caused the second-floor master bedroom to become smaller and more challenging,” Luce says, “which is how the bedroom and bathroom came to merge.”

The merger is a visual tour de force. It is an uncluttered space, 15 by 20, in which the Burtons sleep, bathe and shower — with no physical separation for any of those functions. The tub, a hand-cast resin sculpture that glows gently at night, dominates the room, along with one other artwork, an abstract canvas by William DeBilzan that sits above it.

The shower for two, which forms the back wall of the room, has side-by-side nozzles above a gleaming stainless steel grate that serves as shower floor and drain. The water closet is enclosed in a cube lined with felt made from recycled sweaters.

The architect commissioned specialists in metalwork (some from the custom motorcycle industry) to create the window tracks, doors, door handles and other hardware according to her specifications. Included in that list is her design for a cold-rolled steel trough, 4 inches wide by 1 inch deep, that is inserted between floor and wall wherever the two would ordinarily meet — her Modernist version of molding. The troughs allow the steel floor to expand and contract, Luce says, and they curve up the walls to provide an aesthetically pleasing connection.

Then there’s that horizontal steel trough set low into the living room wall, filled with what look like crystals. It appears to be a decorative touch. But there are no decorative touches in this minimalist environment. Every form must have its function. Burton clicks a lighter and flame shoots up through the bits of recycled glass. It is the fireplace.

Burton says he and his wife are pleased with both the outcome and the costs, which neither he nor Luce will discuss. “We were very careful, and achieved quite a lot for the amount we had to spend,” Luce says. She calls the Burtons “brave” for going ahead with the unusual aspects, and for being willing to spend the money to do it right.

From Burton’s description, he and his wife are economical where it makes sense, and willing to spend where it really matters. Their dining table, for example, is a 1968 design by Italian architect Carlo Scarpa, which Luce calls one of the finest pieces of its kind ever made. But the 12 dining chairs around it are from IKEA. “They are good design, so why not?” Burton says.

When the house below came up for sale, the Burtons bought it and chopped off a part of its backyard to add to their property. Then they slapped a height restriction on the lower house, so that their ocean view could never be obstructed. Then they resold the place. As Luce says, “They really know what they want and what they’re doing.”

Bettijane Levine can be reached at home@latimes.com.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.