Getty’s constant gardener

- Share via

IT was 1973, and eccentric billionaire Jean Paul Getty was planning an ambitious folly for his property in the Palisades: a precise replica of Villa dei Papiri, a grand home destroyed in Herculaneum in AD 79, that would house his collection of Greek and Roman antiquities. He hired the architectural firm of Langdon Wilson to create the villa, and noted landscape architects Emmet Wemple and Denis Kurutz to design the 64 acres around it. The landscaping firm Moulder Brothers was to execute the installation, and 27-year-old foreman Richard Naranjo was to supervise.

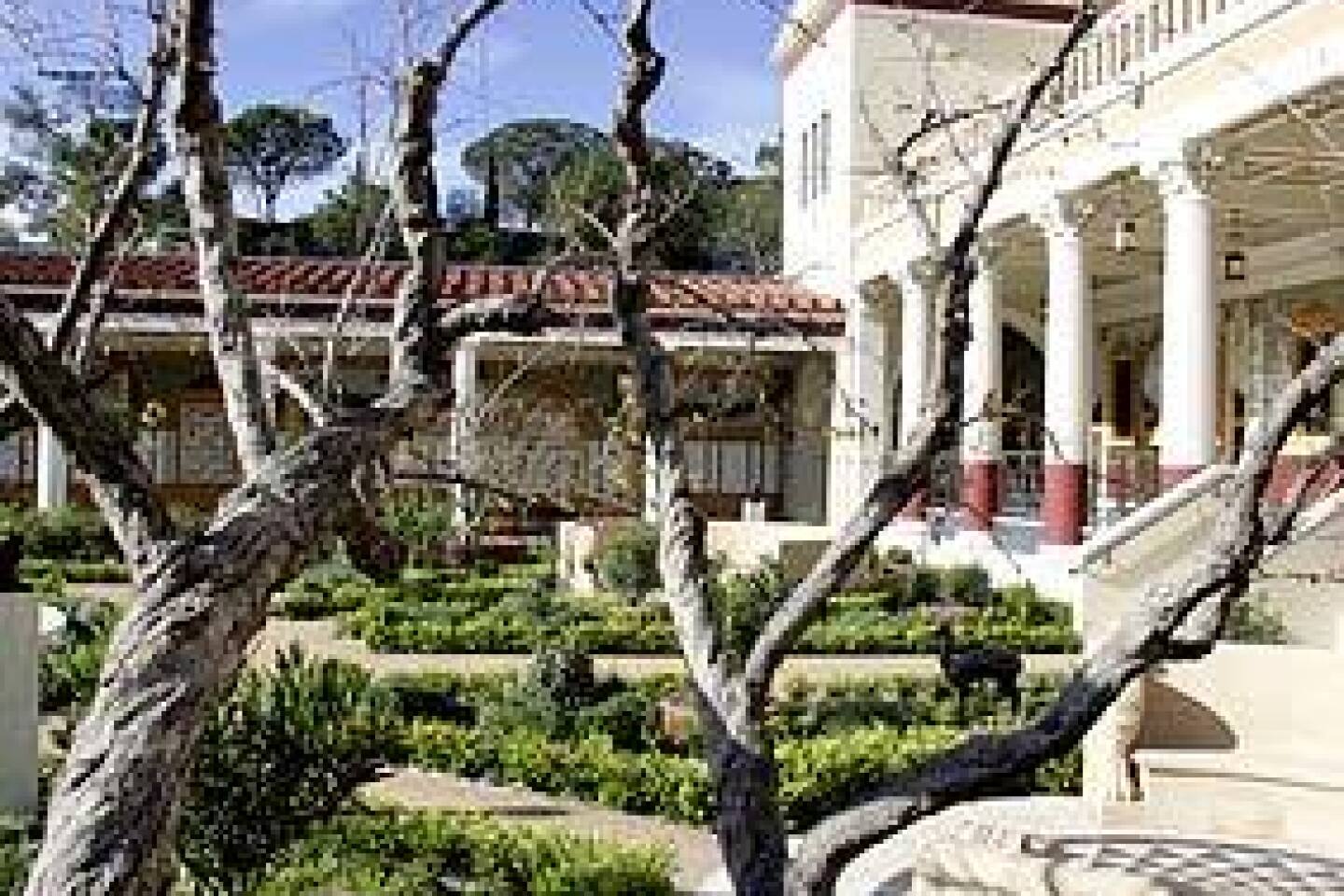

With ancient Roman gardens as their guide, designers envisioned a Getty Villa that looked like it came from the Italian coast 2,000 years ago: an intimate inner courtyard with a reflecting pool; a formal outer peristyle garden with covered walkways, hedged paths and a long, rectangular pool; a walled garden; and an herb garden. Every plant on the plan was chosen to be as faithful as possible to the Villa dei Papiri’s.

It was the job of Naranjo and his crew to track down and plant the flora, from the common (oleander, bay laurel and boxwood) to the unusual (Serbian bellflower, butcher’s broom and medlar trees) — all under intense scrutiny. J. Paul Getty wanted every detail executed precisely, says Stephen Garrett, a London architect at the time and Getty’s liaison during the construction. “Not just the building, but the surroundings and the feeling,” says Garrett, who went on to become J. Paul Getty Museum’s first director. “Getty was extremely interested in the gardens.”

Because the building already had been erected, Naranjo had to devise a way to get massive amounts of soil into the enclosed courtyards. The solution? A conveyor belt set up through a window. Grown trees were brought in that way too, as were about 3,500 boxwood plants. “I planted quite a few of those,” Naranjo says with understatement.

Decades later, and after a nine-year closure for renovation, the villa is set to reopen Jan. 28. And the man who has overseen the planting, the pruning, the watering and the raking of J. Paul Getty’s folly near Malibu is preparing for the next stage of his own life: retirement.

More than 30 years at the villa have yielded some colorful stories, all of which can be traced back to the day when, as the installation of the garden was coming to an end, Naranjo heard that J. Paul Getty was looking to hire someone to maintain the newly landscaped grounds. Naranjo interviewed with Garrett three times in a drawn-out process that involved regular updates with Getty, who was living in England.

In the last meeting, feeling a little exasperated and really wanting the job, Naranjo asked, “Listen, who better can maintain this garden? After all, I did most of the plantings and the installation.” After consulting with Getty one last time, Garrett, who believed the choice was “obvious” from the start, hired Naranjo as head gardener.

“When I first started, Getty’s personal gardener, who’d retired, would come around about once a month,” Naranjo, now 60, says in his soft, low voice. “He’d say, ‘See that tree? I planted that about 15 or 20 years ago.’ Now, I’m doing the same thing.”

Naranjo, tanned face shadowed by his always present Getty Grounds Department baseball cap, walks around the villa with an air of proprietorship. With more than half of his life spent in these hills, he has the right.

In the herb garden (“It really should be called a ‘kitchen garden,’ ” Naranjo notes), he climbs a short, steep, chamomile-covered knoll with the careful pace of a man who has survived a heart attack. His footsteps release a wonderful flowery scent until he stops at an unimpressive looking tree with shriveled fruit hanging from its branches.

“I’m very proud of this,” he says, touching a limb. “It’s a medlar. It’s very typically Roman and it’s very hard to find.” The fruit, he says, is somewhat bitter. Although it is appropriate in this garden, the olive trees, Naranjo concedes, are not. “They should be a fruiting variety. But I knew people would walk on the dropped fruit, then track them into the museum floors.”

He points out capers growing on the stone wall, and basil plants. “I always thought that cilantro was from Mexico,” he says, shaking his head as he moves on. “But it comes from the Mediterranean. The Romans used it for medicinal and spiritual reasons. Same with ruta. I thought crushing it and putting it in the ear was just a Mexican remedy for earaches that my mother knew, but the Romans used it too.”

A love and understanding of plants are in Naranjo’s blood. His father, brother and son are in the business. Trees seem able to talk to him, to tell him if they’re lacking a certain mineral, or which of their branches should be pruned. But his deep knowledge of specific flora — those that grow, and have grown for thousands of years, in the Mediterranean — was learned at the Getty, talking and reading about plants.

Naranjo has learned a lot about non-horticultural matters on the job too.

“I grew up in a very conservative culture,” says Naranjo, a first-generation Mexican American. “When I started working here, I was like a horse with blinders on. The art world is very different from what I knew, and the culture at the Getty, back then, was very eccentric. It was a culture shock,” he says.

Soon after he got the job, Naranjo set up an office in his truck, put together a crew, bought tools and — as head of the grounds department — was sitting at a conference table with 15 or so other department heads.

“It was intimidating at first,” Naranjo says of the regular meetings that included curators, the registrar and Garrett, the museum director. “I was the only nonwhite in the room. It was really hard.” But Naranjo accepted them as they were, and they did the same.

Naranjo’s job title changed often as he took on more responsibility and became an integral part of the team. He got an official office on site (albeit in the converted tack room in the barn), received a letter of praise from J. Paul Getty (who, by some reports, was afraid of flying and never made it back to see the finished villa) and took on more managerial duties.

When asked his current title, Naranjo fumbles. “Director, garden, grounds, Getty, Villa” comes tumbling out before he finally says he’ll have to find his business card. (He’s manager of villa grounds and gardens.) “He’s excellent at what he does,” Garrett says, explaining Naranjo’s promotions and longevity.

Trips to the Mediterranean with Getty Museum principals to visit ancient Roman ruins, museums and gardens were part of the job.

“One of my best memories,” he says, looking out from the main garden to the ocean beyond, “was when I went hiking with Denis Kurutz and [horticulturist] Michael DeHart in the hillsides around Mt. Vesuvius to see how the native plants grow there. It was awesome. We took pictures of the flowers and cataloged them.”

Like the Romans, the staff at the old Getty liked to party — and did so often in the ‘70s and ‘80s. There was a party when the old barn was torn down and a party upon the death of Garrett’s wife, who had asked for one. “We had parties for everything — marriages, divorces, tragedies,” Naranjo says. “We were making the rules as we went along.” A grand fete to mark the temporary closing of the villa and the beginning of the renovations ended with many of the guests — some dressed in togas — splashing in the main pool. (“They all wanted to get in,” remembers Naranjo, adding, “I’m a little too reserved for that.”)

The Getty’s ongoing tradition of celebrating Cinco de Mayo started in 1977 when Naranjo and the grounds staff grilled up carne asada on a portable barbecue outside the old barn. He and his crew chopped tomatoes and chiles for fresh salsa, mashed avocados into guacamole, and chipped in to hire mariachis. Cans of beer cooled in big plastic trashcans, piñatas swung from the eaves, and museum staff danced in the parking lot. “Every year the party just kept getting better and better,” he says.

When the villa closed in 1997, the party shifted to the Getty Center in Brentwood. Its essence shifted too. As the staff grew, the guest list did as well — to 1,700 — and the Getty Center’s cafeteria company took over. “Possible sanitation problems” was the reasoning, Naranjo says. “If they want to do the work, that’s fine with me,” he says, not quite concealing his disappointment. “We were making the meal for years — salsa, guacamole, cactus salad.” He adds quietly, “no one got sick.”

After Getty died in 1976, his burial in Malibu lacked the expected pomp and grandeur. At the end of a workday, Naranjo and a small group of men met the hearse transporting the bodies of Getty and two of his sons, George and Timothy, all of whom were moved to the villa for reburial. In a shaded spot near a bench where Getty often sat, looking out to the Pacific, awaited a mausoleum.

Naranjo says the top of one casket popped off after it came down from the hearse. (Contrary to one version of the event recounted in a documentary film about the Getty family, Naranjo says, the “Mexicans” didn’t flee. They closed the top and finished the job.)

“None of his family was at the burial,” he says, still saddened.

“Getty had seven wives,” Naranjo says, exaggerating by two. Jeanette, the mother of George, had a florist send flowers every month. Naranjo would pick them up at the main gate, carry them up to the site and place them, center front, on the mausoleum. “George’s mother came to visit once,” Naranjo says, not quite laughing, “and when she saw the flowers there, she started yelling at me. ‘I brought those for my son! Not for him! Put them in front of George!’ ” The mother died, but the flowers still come. Another staff member brings them to the site now, instructed by Naranjo to place the flowers on the south side of the grave.

In preparing for the renovation of the villa, Naranjo and his crew dug up much of the landscape, including about 50 mature trees that were to be transplanted elsewhere on the property. “We lost maybe a dozen,” he says, “and that’s because the trees sat in boxes for four years longer than they were supposed to,” a reference to the villa’s original reopening date in 2002.

Now, as neighbors above the villa complain about their view of the site — additional buildings, new driveways, amphitheater and all — it’s Naranjo’s job to “come up with some plants to put up there to block it,” he says gesturing to the hillside dotted with olive trees, Italian stone pines, sycamores and Arbutus unedo, strawberry tree.

Naranjo is friendly with the neighbors, says Jim Bullock, the Getty’s director of facilities and Naranjo’s boss. “He’s just tremendously competent,” he says, noting that people skills are just part of the job. “He knows what plants have worked where and what haven’t,” Bullock says, and he knows everything about the irrigation systems, trucks and tractors and other equipment, and even the property lines. He knows why things were done the way they were — way back when. “He knows the subtleties of the site,” Bullock says.

Looking back, Naranjo sees much change at the villa. Before Getty died, the staff was like family, Naranjo says. “People cared about each other. Everyone was willing to work with you and help you. There was real camaraderie.” When Naranjo needed to propose a budget — the first of his career — people at the museum showed him how. They made sure there was beer, not just wine, at the parties. (“I was a non-wine drinker,” Naranjo says, adding that he has since taken it up. “When in Rome “) When Naranjo and his wife split up, Garrett invited him to stay at his house.

Those personal connections mean the most, Naranjo says. He and Garrett remain friends. He fondly remembers fishing trips in Baja with landscape architect Kurutz, who died in 2003, and cites the encouragement of the villa’s longtime caretaker, John “Slim” Batch. He continues to travel to the Netherlands to visit the Getty Museum’s former librarian — and his former long-time love — Annemieke Halbrook.

Change is inevitable when a small operation grows to become one of the richest cultural institutions in the world. “Since the Getty Center was built,” Naranjo says of the Brentwood landmark, “it’s all become very corporate.”

But the growth also allowed Naranjo to meet artist Robert Irwin and architect Richard Meier — and put him in the middle of their feud. In 1994, as building of the Getty Center was getting underway, Naranjo was appointed to oversee the new site. Meier, who designed the buildings at the Getty Center, lost control of the Lower Central Gardens when the board of trustees offered the job to Irwin, who admits that, at the time, “I had never done a garden.” Naranjo became a partner in the planning.

“Richard was at the garden in Malibu, and I realized that he’d been running it beautifully for all these years,” Irwin says. “I was talking with him all the time, asking him about issues, upkeep, all sorts of things. He taught me a lot.” The two traveled to nurseries together and discussed the merits of one plant variety over another. “If I collaborated with anyone on the garden, it was with Richard. He is very perceptive and has a wonderful way of dealing with things. He understands what the role of the garden was. He wasn’t afraid of it.”

Meier, on the other hand, who was designing the rest of the Getty Center gardens, “was always critical of my gardening techniques,” Naranjo says, laughing. “He’d tell management, ‘I think he’s butchering these trees.’ But I was cutting them back, training them for structure. And Richard [Meier] didn’t understand the idea that some plants are deciduous. He thought they were dying.”

Years later Naranjo spotted Meier talking on his cellphone at the Getty Center, and the gardener tried to duck before the architect saw him. Too late. Meier hung up, caught up with Naranjo and grabbed him.

“He gave me a big hug and kiss on the cheek. I was really surprised,” Naranjo says. “He said, ‘This place is beautiful. These trees are beautiful. That’s just what I had in mind!’ ”

“He did a phenomenal job in terms of the project,” Meier says. “His dedication and involvement were absolutely wonderful. We did have slight disagreements on the spacing of the trees,” he admits, before adding, “they’ve grown in nicely.”

Naranjo remained friendly with both men, and his experiences in Brentwood are among his most memorable.

“It’s gone full circle for me,” Naranjo says. “I was in Brentwood, now I’m back here in Malibu. It’s where I started and where I’ll finish it up.”

He plans to spend his retirement fishing in Baja, traveling to Europe and working on private landscaping projects. He’ll get his hands back in the dirt, a joy that slowly slipped away as his job at the Getty became more about managing people than plants.

He says his last day at work will be in April, and he plans to return for the Cinco de Mayo celebration. “Some people asked me if the party would ever be moved back to the villa once it reopens,” Naranjo says. He tilts his head upward, with a little twist. “I told them, it’s not going to happen. There’s no going back.”

Christy Hobart can be reached at home@latimes.com.

*

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX)

Planting favorites

During more than 30 years at the Getty Villa, gardener Richard Naranjo has seen some Mediterranean plants flourish — and others founder. Some favorites that he says will do well in home gardens:

Arbutus unedo, strawberry tree: Naranjo likes its nice umbrella structure and bright (but bad-tasting) berries. Can be pruned as a shrub.

Chamaemelum nobile, chamomile: A great substitute for grass, plus you can make tea.

Cydonia oblonga, quince: These trees are easy to grow, and their fruit is hard to find in markets. Plant your own and make jam out of the tart fruit.

Ficus carica, fig: One of the villa staff’s perks is that they can eat the figs off these trees. Naranjo prefers white fig varieties.

Laurus nobilis, sweet bay laurel: Because Romans believed that the bay tree was never struck by lightning, its leaves became a favorite for adorning crowns. It’s nice to have for flavoring soups and stews. If ants invade your home, Naranjo suggests placing fresh leaves in problem areas.

Punica granatum, pomegranate: Naranjo cites its lovely structure and beautiful fall fruit that look like “ornaments on the tree.”

Rosa damascena, damask rose: A fragrant old rose used by the Romans to scent drinks — and the soles of their feet. The roses are hard to find but are worth the effort for their scent.

Christy Hobart

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.