Learning Chinese more than a language lesson

- Share via

Beijing, China

An old Chinese proverb sums up the three months I spent studying Mandarin in Beijing: To suffer and learn, one pays a high price, but a fool can’t learn any other way.

The famously difficult Chinese language could make a fool out of anyone. Standard Chinese, known as Mandarin or Putonghua, has tens of thousands of characters, many taking more than 20 strokes to write, and a transliteration system called Pinyin that expresses Chinese words in the 26-letter Latin alphabet of English.

Further complicating matters, Mandarin is a tonal language, meaning that the same Pinyin word has four definitions depending on the intonation.

More than 20% of the world’s population speaks Chinese. But while studying it last year at Beijing Language and Culture University, I often wondered how Chinese children ever learn it. Generally, I felt like a child, or at least deeply humbled. But on those rare occasions when I could read a sign or tell a cashier I didn’t have any small change, I felt like Alexander the Great at the gates of Persepolis.

You don’t learn Chinese in three months -- or at least I didn’t. Basic Chinese at the Monterey-based Defense Language Institute Foreign Language Center is a 63-week course. But spending a semester in BLCU’s short-term, accelerated program struck me as a good way of getting to know Beijing, which had proved elusive on my first visit 10 years ago, chiefly because I couldn’t communicate.

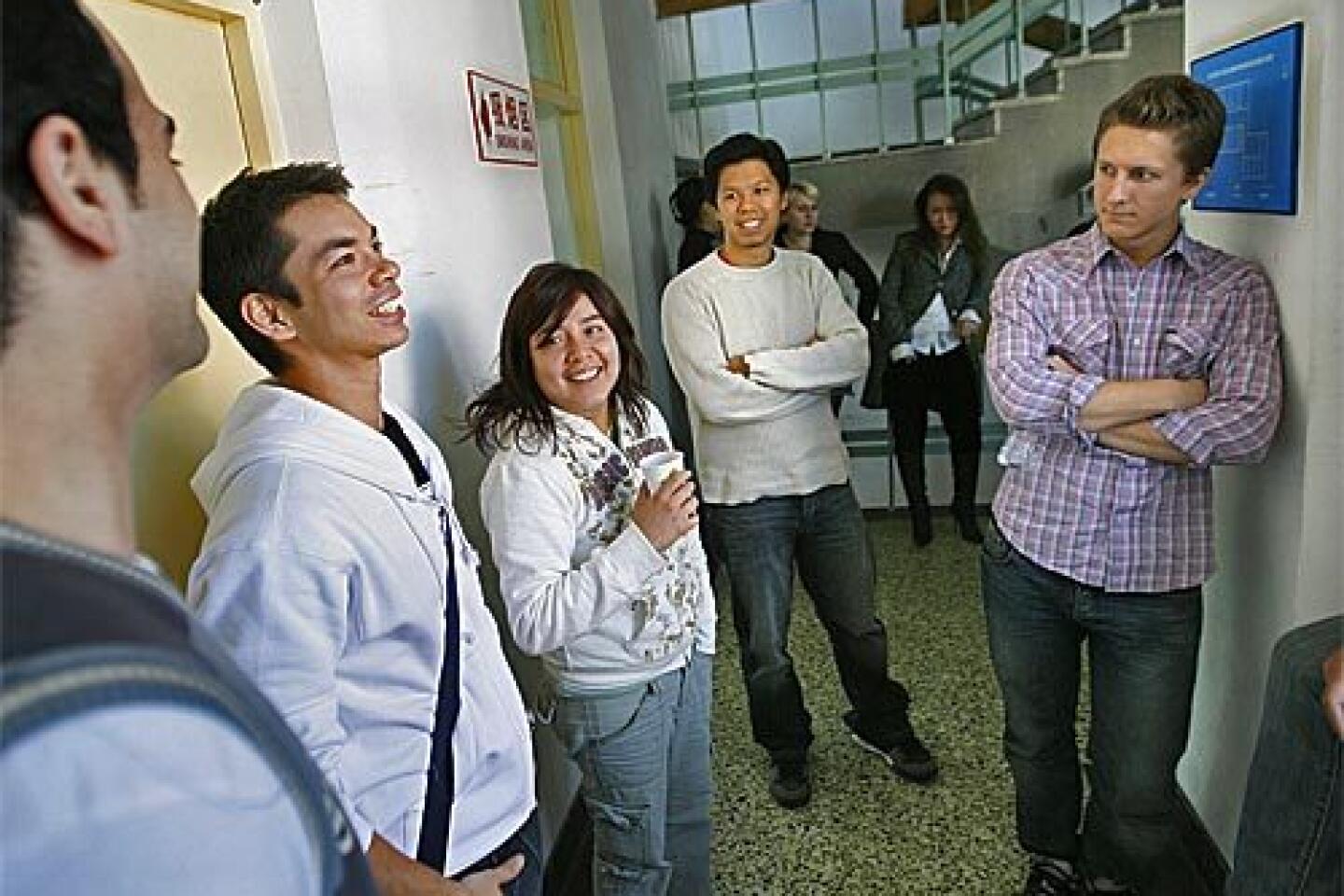

BLCU specializes in teaching Chinese to overseas students. But there were many other schools in Beijing to consider because the demand for Chinese language training is growing exponentially. The Chinese Ministry of Education estimates that 40 million people around the world studied the language last year. Moreover, China’s popularity among American exchange students increased 90% between 2002 and 2004, and 35% more in 2007.

A Chinese professor at my alma mater, Mount Holyoke College in Massachusetts, recommended BLCU, a state-approved institution founded in 1962 in the leafy university district of Beijing. It was the right choice for me, as it turned out. It’s near the academic powerhouses of Peking and Tsinghua universities, and it is well-known to taxi drivers.

The school has a student body of about 15,000, a third from China studying to become Chinese teachers or preparing for careers that require a foreign language. Like American college students, Chinese undergraduates at BLCU play sports, party and call home to ask their parents for money.

The rest of the students come from more than 120 countries around the world and generally pay their own way. They have to hit the books hard just to keep up in accelerated Chinese class, where the approach is known as stuffed duck.

Inside the ivory tower

When I arrived here, I thought I would enjoy class from 8 to noon every weekday morning and spend the rest of the time tooling around Beijing.

I could easily have found an apartment off campus, but that required a residence permit from the local police. So I got a single in a dorm, figuring that living like an undergraduate at age 52 would be the worst indignity I would have to endure.

I had it all backward.

The campus, which occupies most of a city block close to the heart of Haidian District around Wudaokou subway station, is an Oriental ivory tower, surrounded by walls with gates locked at midnight (though pub crawlers are admitted after that with a little pleading). It was the dreary end of a Beijing winter when I arrived, so all I noticed at first was that BLCU had everything a student could need: ATMs, a library, bookstore, post office, conference center, market, hair salon, copy shop and gymnasium with Olympic-size pool.

Besides the cafeteria, which serves hot Chinese meals on penitentiary-style aluminum trays for about 25 cents an entree, there are several small restaurants specializing in foreign cuisine (though my taste buds told me that everything came from the same kitchen). I favored the LaVita Café, where I studied in the morning and drank a lot of coffee. The Muslim restaurant near the basketball courts was by far the most popular, chiefly for its delicious flat bread cooked on a round ceramic oven by a big, vicious-looking baker wielding a long wooden paddle.

Scattered around campus are 17 dorms, a few new high-rises but mostly two-story, gray brick buildings, vintage 1980 or so, inevitably fronted by a parking lot full of dilapidated bicycles. My dorm was No. 13, near the west gate, with a front desk manned 24/7 by staff members who knew but mostly refused to speak English.

My room, which cost about $400 a month, was on the second floor and far more comfortable than I had expected.

Its walls bore Scotch-tape marks from previous occupants. It had a mini-refrigerator, Internet hookup (for $20 more a month), a hard single bed, a card-operated telephone and a television. (The TV showed only state-sponsored CCTV news in English and a Korean-language station that aired reruns of “CSI: Miami” nightly, with Korean subtitles.) The private bath had an unenclosed shower dispensing water hot enough to make instant noodles.

About once a week, a washer in the faucet handle broke so I couldn’t stop hot water from gushing out of the shower. By the time the plumber came, the whole room was a steam-filled sauna. And though the heating system was powerful, it was centrally operated. When I started to sweat, I asked a floor attendant how to turn it off. She rolled her eyes and, with the disdain of an upperclassman, said, “Open a window.”

Most foreign students furnished their dorm rooms from the campus Friendly Store, stocking goods as varied as bean paste and blow dryers, the latter priced at just $6 because they were manufactured in India, I was told.

But wanting to make my dorm room a place I could come home to, I took a cab to the IKEA on the Fourth Ring Road (which is just like IKEAs everywhere) and visited the Panjiayuan antiques and flea market on the southeastern side of town one Sunday morning. I could never have carried everything I wanted to buy but came away with some treasures: a bubble-shaded ceramic lamp in the shape of a Ming Dynasty courtesan, a hand-painted scroll of Chinese men and caged birds, and a kitschy mantel clock faced with a cheerful picture of Chairman Mao.

Instruction begins

Then the academic semester began with a placement test, given in a spartan classroom to about a dozen primarily English-speaking students. Students were grouped according to their mother tongue, with young Korean speakers dominating by a wide margin.

Instruction at BLCU starts in the students’ first languages, progressing after about a month to an all-Chinese learning environment.

I sharpened my pencils and prepared for the worst. But first, the teacher asked those of us who had never studied Chinese to raise our hands and said, “You know nothing. You can go.”

So I joined the most ignorant class in BLCU’s accelerated Chinese program, and my status never changed.

A month into the semester, I did so poorly on a practice test that it finally dawned on me I needed to study at least four hours a day to enjoy and benefit from class. I did all the exercises in my textbooks and made flashcards with Chinese characters on one side and Pinyin on the other.

The only thing I didn’t do to get ahead was to hook up with a language partner, though native English speakers like me were in such hot demand that Chinese students occasionally tailed me across campus working up the courage to suggest we team up for English-Mandarin conversation.

Soon I was doing better, and my classmates noticed.

They were a wonderfully mixed and motley crew from all the corners of the world where people are realizing that their futures may be inevitably tied up with China.

I spoke French with Joelle, a tall young woman born in the Republic of Congo and educated in Poland. Roger, from Brazil, planned to study with a Chinese martial-arts master.

Michael was an E.M. Forster-esque Englishman, between jobs in Asia. Tatyana came from Vladivostok and spoke only Russian, so she used a dictionary to translate the teacher’s English into her mother tongue.

Mohammed, from Egypt, had to contradict people who assumed he had a harem, and we all thought that Shinji, a Korean with a sociology degree from the University of Chicago and a build like Superman, worked for the Central Intelligence Agency.

There were only two other students from the U.S., one a Chinese American girl who wasn’t sure whether she wanted to be a writer or a dentist, the other a thirtysomething New Yorker whose excellence at Chinese quickly made him the class favorite. When our teacher struggled to explain the nuances of Mandarin in English, Jacob stepped in to assist her.

We were given three textbooks on Chinese grammar, listening and speaking. Three teachers -- laoshi in Mandarin -- rotated with them. In China, the teaching profession is still highly revered. Anyway, I revered my instructors, especially Wu laoshi, a thin, bespectacled woman in her 30s with an unfulfilled yen to see the world.

On a bench near my dorm, she prepped me for my role as laoshi in a skit my class reluctantly performed at the spring talent show. Later, we commiserated about some of my fellow students’ perpetual tardiness and obvious failure to prepare.

I told Wu laoshi not to worry, bie zhaoji in Chinese. Our class was full of oddballs.

She didn’t know that word, but when I explained, I got a good laugh out of her.

Squeaking past midterms

BLCU cleared out during Golden Week, the big spring holiday in China. I went to Tibet but got back in time to prepare for midterms. We were graded on a 100-point scale, with no curve.

I came very close to flunking.

Never mind. Winter yielded to spring, with translucent skies and lilacs by the post office.

Every morning I woke up to the rubber-soled footfall of the security force running in a phalanx past my window. I grabbed coffee at LaVita and went to class. My attendance was sterling even if my grades were not.

Every afternoon, I studied hard and even learned a little Mandarin I’ll probably forget.

But I won’t ever forget watching Chinese boys in droopy shorts play basketball, chatting with Wu laoshi on a bench, eating hot flat bread from the Muslim restaurant, and the smell of Chinese lilacs.

susan.spano@latimes.com

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.