Has paradise disappeared? Chasing the Hawaiian ideal in modern Honolulu

- Share via

HONOLULU — What happened to the watercolor dream?

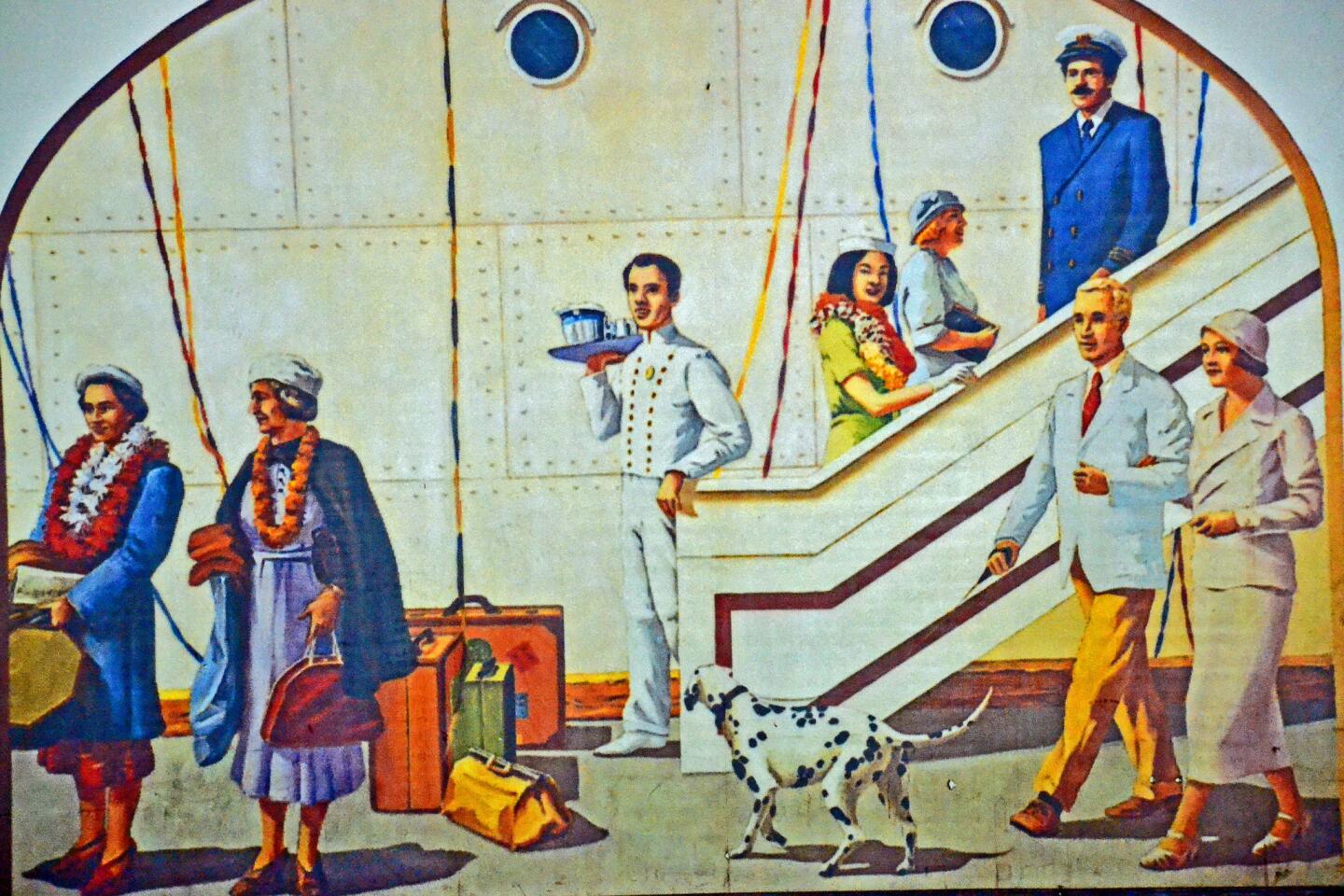

That’s the dream that Matson built. Matson, the passenger and shipping company, practically invented Hawaii tourism.

In 1908, the first Matson passenger vessel joined its fleet, and elegant white ships were soon sailing people from Los Angeles and San Francisco to this new tourist destination called Hawaii.

From the moment the Aloha Tower, the Hawaiian Gothic clock and light tower at Pier 9 winked into view, you could feel the excitement. Suddenly, bronzed boys and men were diving for quarters and half- and silver dollars tossed from the ship; you could hear the strains of the Royal Hawaiian band, and when you disembarked, you’d be draped with leis so fragrant you’d swear you were in heaven.

In many ways, you were.

You could stay at a Matson-owned hotel. When it was time to go home, you reboarded a Matson liner and threw your lei into the ocean, perhaps promising yourself you would return.

If your memory of the trip began to fade, you had only to look at the gloriously decorated menus from the Matsonia or the Lurline or one of the other ships in the fleet, menus you had framed and then hung on the wall of your rec room. The light never dimmed.

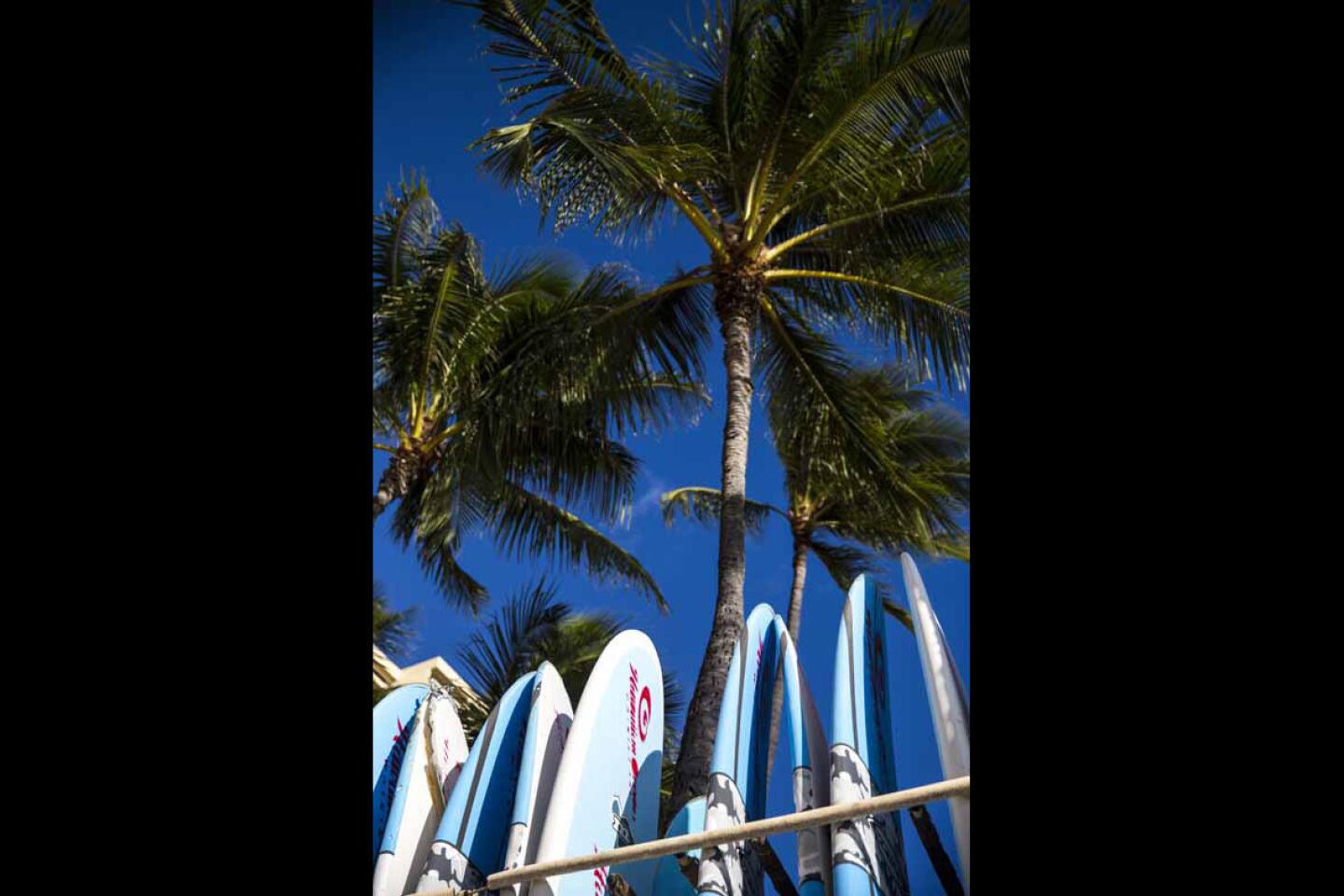

But look at Honolulu today and you wonder whether paradise has disappeared. The boulevards’ high-end shops mimic those in Vegas, as does the traffic; Honolulu’s ranks among the worst in the nation. Northeasterly trade winds blow about 80 fewer days a year than they did 40 years ago, according to a 2012 University of Hawaii study, leaving the city hot and sticky.

Honolulu is “hugely cosmopolitan,” said Theresa Papanikolas, who curated the recent exhibition “Art Deco Hawaii” for the Honolulu Museum of Art, which featured some works commissioned by Matson.

Although aspects of the city she now calls home are relaxing, Honolulu has “the same problems as anywhere on the mainland,” said Papanikolas, a former L.A. resident who worked at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

And yet....

You can still find the stuff of dreams. On a recent 48-hour trip, I revisited some of the cornerstones of that early vacation vision, found some new favorites and, as always, delighted in the people and places that keep the light on for us.

Thelma Kehaulani Kam, director of cultural services for Starwood hotels, including the Moana Surfrider and the Royal Hawaiian, soothed my troubled soul at the end of a tour of the Royal, which was once owned by Matson. When people say “aloha,” she said, the meaning is deeper than hello or goodbye.

“‘Alo’ is the physical part of what the person sees — the smile, the nod — it’s the person coming close to you,” Kam said. “‘Ha’ means breath.

“When you put that word together, what you are telling that person is ‘Take all of me….’ You are giving all of yourself without the expectation of anything in return.”

Aloha.

::

You know the name Matson from the trucks you see trundling to Southern California ports, but you may not know that Matson had a glorious past sailing passengers to Hawaii.

From its humble beginnings, Matson grew to become an economic and cultural powerhouse in Hawaii and on the mainland. Its ships carried celebrities (Jack Benny, Mickey Rooney, Rosalind Russell, Jimmy Stewart, Shirley Temple and Mel Torme) and common folks alike.

It also ventured into the hotel business; the Moana and the Royal Hawaiian still stand as testaments to foresight and genius.

Here’s a brief look at Matson Co.:

1849: William Matson is born in Sweden

1867: Matson arrives in California

1882: Matson Navigation Co. is founded. He sails his schooner Emma Claudina (with help from sugar magnate Claus Spreckels) to Hawaii.

1887: The first of the vessels named Lurline joins the fleet. It later runs aground.

1908: The second Lurline, a 51-passenger steamer, is christened by Matson’s daughter, Lurline.

1910: Encouraged by the success of the Lurline, the Wilhelmina is introduced.

1917: Matson dies at 67

World War I: The government requisitions most of the Matson fleet.

1927: The speedy Malolo becomes the hot-shot ship ferrying passengers to and from Hawaii.

1930-32: Mariposa, Monterey and a third Lurline are built.

1934: Passengers sometimes bring cars aboard the Lurline, but this passenger brings a Lockheed Vega on a sailing to Honolulu. Her name: Amelia Earhart.

Dec. 7, 1941: After the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Lurline, Mariposa, Monterey and Matsonia become troop transport ships, often carrying more than 3,000 service members at a time.

September 1945: VJ Day marks Japan’s surrender on Sept. 2. By the end of their wartime service, the four Matson passenger ships have traveled nearly 1 1/2 million miles and carried nearly three-quarters-of-a million passengers/troops.

April 15, 1948: The Lurline returns to passenger service after a $20-million refurbishment (about $198 million today, after adjusting for inflation).

1955: Thanks to a new building program, the Mariposa and Monterey are born again; the old Monterey becomes the Matsonia.

1958: Actress Dorothy Lamour christens the Matson sales office at Powell and Geary streets in San Francisco; she had sailed with Matson in 1941.

1963: The Lurline is damaged and sold.

December 1963: The Matsonia becomes Lurline No. 4. It is the last passenger ship by that name, but in 1973, a freight vessel is christened Lurline.

1970: Matson leaves the cruise business.

Sources: Matson.com; “To Honolulu in Five Days: Cruising Aboard Matson’s S.S. Lurline,” by Lynn Blocker Krantz, Nick Krantz and Mary Thiele Fobian; The Los Angeles Times

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.