- Share via

LAREDO, Texas — Jeanette Silva still hasn’t decided what she will do when a census packet arrives at her home a few miles from the banks of the Rio Grande.

The 40-year-old pastor feels conflicted — torn between what she sees as the benefits it could offer her community, including her daughter, along with the potential risks for her undocumented husband.

“My little girl will have more support,” said Silva of the couple’s 4-year-old, Deborah. “But there is always an uneasiness, a fear — especially right now — of federal officials.”

Last month, as a result of a U.S. Supreme Court ruling, President Trump abandoned his efforts to add a citizenship question to next year’s census. Now activists nationwide are campaigning to assure immigrants it is safe to participate in the once-a-decade tally that determines how federal money and power is apportioned.

But many here fear that irreparable harm already has been done, and they are bracing for a record undercount.

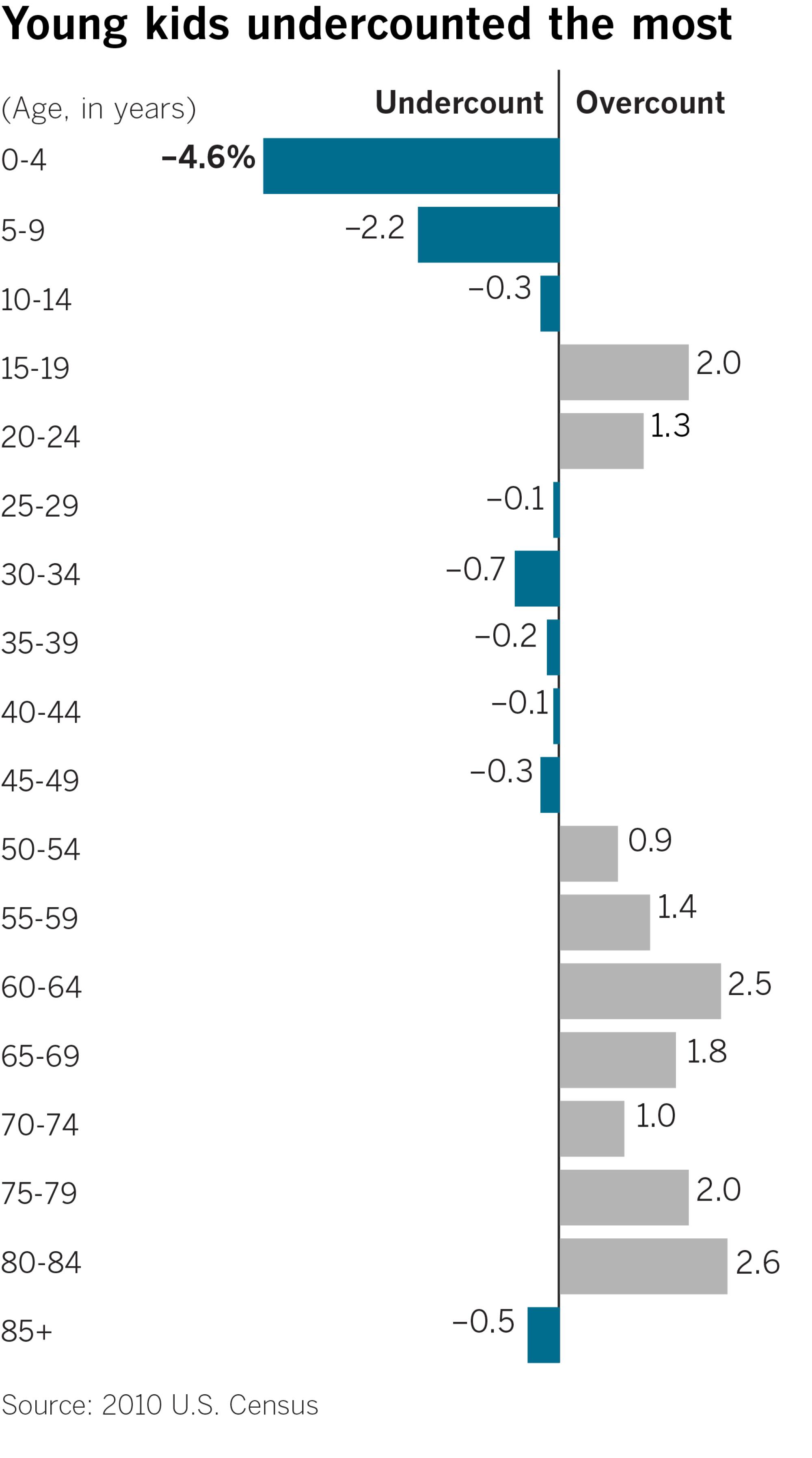

Among the groups most at risk of not being fully tallied are children younger than 5. For decades, the U.S. Census Bureau has struggled to count that demographic. In 2010, roughly 2 million were omitted, more than any other age group.

The problem is more severe for Latino children, who accounted for 40% of those under 5 who were missed in the last tally.

Webb County, Texas, home to Laredo, ranked the worst nationwide, according to data provided by William O’Hare, a demographer who has studied the 2010 undercount for the Census Bureau.

The most pronounced undercounts have come in areas that, like Laredo, have large populations of undocumented immigrants, O’Hare found.

Some demographers expect the pattern to worsen.

Laredo is predicted to have one of the lowest response rates to the 2020 census, according to the Census Bureau. Southern California cities like Los Angeles and border communities also rank among the country’s toughest to fully count.

The impacts of another undercount will be far-reaching, said Cassie Davis, a research analyst at the Center for Public Policy Priorities, a think tank based in Austin.

“When young children are not counted properly,” Davis said, “it affects them for their whole childhood.”

Census data is used to distribute nearly $900 billion in annual federal funding, supporting schools, healthcare, food stamps, foster care and special education. Latino children, who disproportionately live in poverty, are among the most in need of government help.

In Texas, some local officials have estimated that they will receive as much as $1,578 less per year in federal funding for each person who is not counted in next year’s census.

The Census Bureau says a complex set of social and economic challenges contribute to why Latino children are overlooked, citing, among other factors, language barriers and frequent moves between rental units for some families. The agency is banking on outreach, education and reforms to how the count is administered to encourage as many people as possible to participate.

Potentially frustrating those efforts is Trump’s failed attempt to add a citizenship question to next year’s count. The move aligned with the president’s vows to crack down on illegal immigration but ultimately faltered despite his threats to move forward even after the Supreme Court ruling. Nonetheless, the White House effort drew wide publicity and many here in Webb County are now concerned that information collected by the census could be used to find and deport people who are in the country illegally. The agency, for its part, says census responses are confidential and can be used only for statistical purposes.

“To most people the Census Bureau is not any different from ICE,” said Deborah Griffin, a retired Census Bureau researcher, referring to Immigration and Customs Enforcement, which conducts deportations.

In Webb County, where 96% of residents are Latino, “everyone knows someone who is undocumented,” said Arturo Garcia, director of the Laredo Community Development Department.

Garcia sits on the recently formed Complete Count Committee, which is made up of city and county leaders, and is focused on ensuring that nobody goes uncounted. Recent headlines about ICE raids, he said, have put the community on edge.

“One parent might be undocumented and the other a U.S. citizen.... Well, their kids are American citizens who need to be counted,” Garcia said. “But it’s difficult because on one hand people have a genuine fear of the federal government, but on the other we’re asking them to trust the federal government.”

In an effort to inform the community, the panel recently released a series of web and television ads, in English and Spanish, urging participation. The videos stress that any information shared with census officials is confidential.

Since last year, more than two dozen states have created similar committees, with several others at the local level. Lawmakers in California have set aside more than $150 million in budget funds for programs to ensure a complete enumeration of vulnerable populations.

But Texas — the state with the second largest Latino population in the country — hasn’t targeted any money to tackle an undercount. In 2010, Texas lost the most federal funding of any state — $119 million — from five federal programs because of the undercount of young children, according to research by Count All Kids, an umbrella group of national, state and local organizations.

Several outreach groups, including NALEO Educational Fund, a national organization that advocates for Latino participation in civic life, are working in communities including Laredo to ensure an accurate tally.

“We need to educate adults because children can’t make themselves count,” said Arturo Vargas, the group’s chief executive officer.

A report by the Leadership Conference Education Fund, a Washington-based civil rights group, found that funding for programs that many Latino children rely on — special education grants, childcare, foster care — could be severely affected by an undercount.

The federal government allocates $8.3 billion each year for Head Start, the pre-kindergarten programs aimed at helping children develop early reading and math skills. The report found that 37% of Latino children nationwide participate in Head Start.

While the funding for such programs is crucial to help Latino children, activists say it’s difficult to ease concerns and avoid an undercount amid near-constant headlines about raids.

On a recent afternoon, Mike Smith, who runs a community center in Laredo that has housed families seeking asylum, sat behind a desk stacked with fliers announcing upcoming protests and vigils.

Smith, who also serves as a pastor at a Laredo church, said that his phone at the community center, less than a mile from the border, has been ringing for months with calls of concern. People are even afraid to go to work, Smith said.

As Smith sees it, an undercount is inevitable and next year’s will be worse than those in the past.

“There is no question of another undercount, probably more so than last time,” said Smith, who grew up in Laredo and has family members living in the country illegally. “You can tell a lot of these families that the information will be confidential, but there is a lot of fear and rightfully so.”

Smith works alongside local groups that hold sessions informing people that they don’t have to live in the shadows and that they have rights. But a fear of the federal government persists, he said, adding that many also are concerned about state measures such as a 2017 Texas law banning sanctuary cities.

In spite of the fears, some in Laredo say they take pride in having their children counted. They say it represents an official acknowledgment of their existence and role in the U.S.

“I may never count on paper, but they will,” said Ilse Mendez, 32, whose family moved to Laredo from its sister city in Mexico, Nuevo Laredo, when she was 2 years old.

Mendez’s mother crossed with her into Texas through the Rio Grande, inspired largely by a desire to get better medical treatment for Mendez’s sister, who was born with a birth defect. Because Mendez was 2 at the time, she qualified in 2013 for temporary protection to stay in the country under an Obama-era policy known as Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals. The policy, DACA for short, is now before the Supreme Court, which is set to rule on whether the Trump administration can rescind the protections.

For Mendez, who works in the healthcare system, it’s critical that her two youngest children — Aaliyah, 5, and Aalizah, 3, both U.S. citizens — be counted.

“They are just as American as any child,” she said on a recent afternoon as she and her children sat on benches in a park along the banks of the river. Across the Rio Grande in Mexico, men held fishing rods in the water and teenagers dipped their feet in the slow current to escape from the heavy humidity.

Silva, the pastor, said that although the issue continues to weigh on her, she too is leaning toward filling out the survey.

On a recent Sunday inside her tiny storefront church, Silva preached a message of love and belonging — immigrants and asylum seekers, she said, belong here in the United States.

“They deserve our love, our protection,” she said, her eyes closed and hands pointing at the tile ceiling. “We are all one.”

In recent weeks, many of her congregants have skipped church, she said, fearing ICE officials might show up. At the end of her 30-minute sermon, the few congregants in attendance filed out quickly into the muggy afternoon air.

“We’re a blended family,” Silva said. “We all count and should not be fearful.”

Lee reported from Laredo and Kambhampati from Los Angeles.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.