The U.N. is flying and busing migrants through Mexico back to Central America

- Share via

JUAREZ, Mexico — A United Nations agency, with funding from the U.S. State Department, is transporting thousands of immigrants from the U.S.-Mexico border back to Central America in a program that has drawn the ire of migrant legal advocates. The advocates question whether migrants fully understand their rights when they accept free plane and bus tickets home.

The program was in full swing Tuesday in this border city opposite El Paso, where 63 Honduran migrants boarded two buses chartered by the U.N.’s International Organization for Migration, which has transported more than 2,200 Central American migrants home from Juarez and Tijuana so far this year, a spokesman said.

The $1.65-million program, called Assisted Voluntary Return, is funded by the State Department through next month, when it’s expected to expand east to the border cities of Nuevo Laredo and Matamoros.

“We’ll continue as long as there is a need and people are seeking assistance returning home,” said Christopher Gascon, chief of mission in Mexico for the IOM, known there as OIM.

Gascon said his agency is trying to protect migrants making the perilous journey south.

“They face the same dangers on their way home as they do on the way north. That clearly demonstrates the need,” he said.

Migrants using the program include those who have given up on attempting to cross the border, those seeking political asylum in the U.S. for the first time and asylum seekers returned by U.S. immigration officials to await the outcome of their U.S. immigration court cases in Mexico under the Trump administration’s “Remain in Mexico” policy.

Migrant legal advocates worry about the latter group, saying the U.N. agency is encouraging asylum seekers to drop their cases without sufficient legal advice, an allegation IOM officials dispute.

So far, 37,578 asylum seekers have been returned to Mexico to await the outcome of their U.S. immigration cases. Of those, about 400 have boarded IOM buses home, Gascon said.

Leaving is a big risk for those who still want to pursue asylum in the U.S., legal advocates said. There’s no guarantee that if migrants leave, they will be able to return through Mexico legally, and if they fail to appear for a U.S. immigration court hearing, a judge could issue a deportation order, in effect closing their case and limiting future opportunities for asylum.

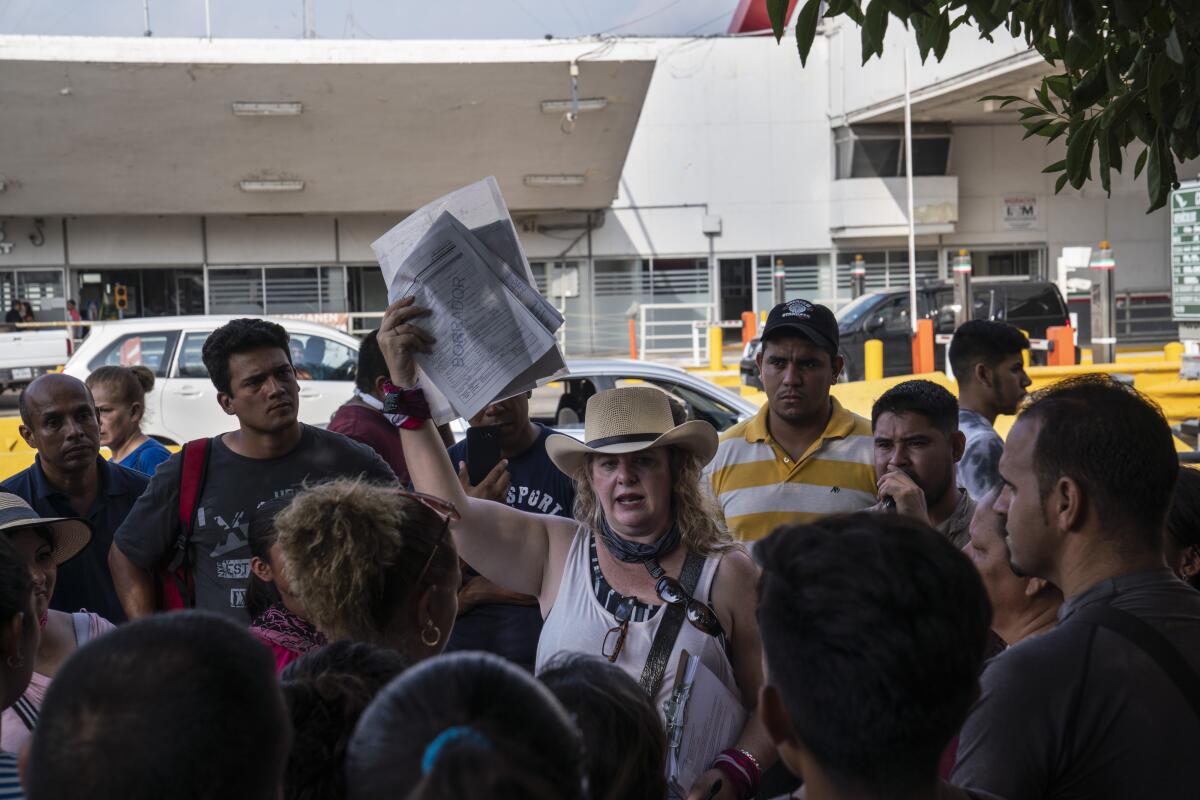

Immigration lawyers are scrambling to better inform migrants in Mexican border cities of their rights before they board IOM buses south. Last month, 30 international advocacy groups sent a letter to the U.N. agency’s chief saying that they feared the program was returning migrants to countries they had fled “out of desperation, not choice” and that those with pending U.S. asylum cases “may not fully understand the consequences of failing to appear whenever summoned by a U.S. immigration court.”

“Is it really voluntary if people don’t understand the consequences of what they’re doing?” said Nicolas Palazzo, a staff attorney with one of the groups that signed the letter and works with migrants in Juarez for the El Paso-based Las Americas Immigrant Advocacy Center. “Our concern as advocates is that people are not making a truly informed decision about going home.”

The agency responded this month with a letter defending the program, which started in Mexico City as large caravans of Central American migrants passed through on their way north to the U.S. border in October.

“A number of people were drawn into that movement, that flow, and at some point came to realize that it was not at all what they had expected — much longer, much more difficult. People started seeking assistance returning,” Gascon said.

His agency set up kiosks at a stadium in the capital and reached out to migrants in shelters, busing several hundred back to Central America. In the months that followed, the agency started busing and flying migrants home from Mexicali, Monterrey and Tijuana, he said.

This month, IOM has transported about 70 migrants from the U.S.-Mexico border to Central America a week, Gascon said, most by bus, with stops in Mexico City and Tapachula on the Mexico-Guatemala border. Some returned on flights from Tijuana, and Gascon said the agency plans to return more migrants by plane soon. News about the program was first reported earlier this month by the Reuters new agency.

Three-quarters of the migrants his agency sent back went to Honduras, a fifth to El Salvador and the rest to Guatemala and Nicaragua, Gascon said. More than half were families; about 100 were unaccompanied youths.

Before migrants leave, they receive an orientation from Mexican immigration officials about the “implications and consequences” of returning and are screened by the U.N. program, Gascon said.

For unaccompanied youth, the U.N. agency contacts relatives and Mexican social services to coordinate returns, always by plane, Gascon said. The agency tells adult migrants in the Remain in Mexico program that returning to Central America could jeopardize their asylum case; that if they fail to appear in U.S. court, a judge could order them deported in their absence, which could undermine their future asylum applications. IOM staff ensure migrants are fit to travel and feel safe returning home, Gascon said.

“We don’t want to support someone to return who is fearful for their life,” he said. “… We make sure that people are aware of all of the other options and they weigh them.”

Gascon said voluntary returns are only part of the agency’s response on the border. It also provides support to migrant shelters in Juarez and Tijuana and is exploring ways to help Central American migrants find housing and employment in Mexico.

Alex Rigol, who leads IOM’s Juarez office, said the agency distributes medical supplies and toiletries to some of the 15 local migrant shelters where it’s also trying to improve infrastructure, “to help secure the people who decide to stay.”

Rigol said staffers don’t advertise the U.N.’s voluntary return program with posters or brochures. “We don’t promote it. We just reach out to the directors of the shelters to make sure they inform people,” he said.

The U.N. agency’s staffers in Juarez declined to allow The Times to observe them screening migrants this week, citing privacy concerns. The shelter where migrants boarded the agency’s chartered buses refused to allow migrants to be interviewed because of security concerns.

Palazzo and several other migrant advocates met with the U.N. agency’s staff in Juarez on Aug. 14 to express concern about the legal information being given to migrants.

The U.N. agency’s staff in Juarez agreed to work with Palazzo to improve legal information provided to migrants, he said. They also promised to refer migrants to him who should be exempt from Remain in Mexico, including pregnant, disabled and LGBTQ migrants.

Palazzo called busing migrants south “another step towards deterring and dis-incentivizing asylum seekers from making their lawful claim in the United States.”

But he said the travel program hasn’t had a major impact yet. Nearly 16,000 migrants have been returned to Juarez under Remain in Mexico; an additional 5,000 were waiting to apply for asylum this week and only a fraction — about 500, according to IOM — have returned to Central America under the U.N. program.

“People are willing to stick it out,” Palazzo said.

But some migrants are not.

Juan Santos was among dozens of Central American migrants in Tijuana who signed up for the U.N. agency’s free flights back to Honduras this month.

As he was arranging for the flight at a local migrant shelter, Santos explained that he had come to the border seeking asylum in the U.S. with his 6-year-old daughter, Kenia. They had been returned to Mexico with a U.S. court date in January — too long to wait without a job, he said.

“We’re losing too much money sitting here, waiting,” Santos said. “And with a little girl, it’s complicated to be here in Tijuana. I can’t leave her to go to work all day.”

He said he knew he wasn’t alone.

“In this moment, many have lost hope,” he said.

Volunteer lawyers and nonprofits were expanding migrant legal services this month in Juarez and other Mexican border cities, but not enough to meet demand among asylum seekers.

Last weekend, Atlanta-based nonprofit Lawyers for Good Government flew half a dozen immigration lawyers from across the country to Matamoros to help asylum seekers prepare for upcoming Remain in Mexico court dates. The group hopes to establish offices in Matamoros and several other Mexican border cities just as the U.N. agency plans to start busing migrants there home.

As soon as the group of lawyers crossed the border bridge from Brownsville, Texas, to Matamoros on Saturday, hundreds of asylum-seeking families living in tents next to the bridge surrounded them, clutching U.S. immigration paperwork.

Claudia Oliva Garcia, 42, said she couldn’t return to Honduras. She had fled with her husband and three children in June after receiving death threats from gangs related to the family’s convenience store. Her mother had applied for a visa to bring them to the U.S. in 2008, but they couldn’t wait any longer. This month, they crossed the Rio Grande illegally and were returned to Matamoros by Border Patrol under Remain in Mexico. They had been waiting 18 days, and their first U.S. immigration court date wasn’t until Oct. 9, but Oliva said they had no plans to leave.

“I want to do everything legally. I won’t miss any court dates — none,” she said.

Union Tribune reporter Wendy Fry and special correspondent Ingrid Giese in Mexico contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.