- Share via

ILIAMNA, Alaska — A brown bear loped across rolling green tundra as Charles Weimer set down a light, single-engine helicopter on a remote hilltop.

Spooked, the big grizzly vanished into alder thickets above a valley braided with creeks and falls. Weimer’s blue eyes scanned warily for more bears. He warned his passenger, Mike Heatwole, to sit tight as the blades spun to a halt, ruffling red, purple and yellow alpine flowers.

The two men, each slim with a goatee, stepped out into the enveloping silence of southwest Alaska’s wilderness. Before them stretched two of the wildest river systems left in the United States. Beneath their feet lay the world’s biggest known untapped deposit of copper and gold.

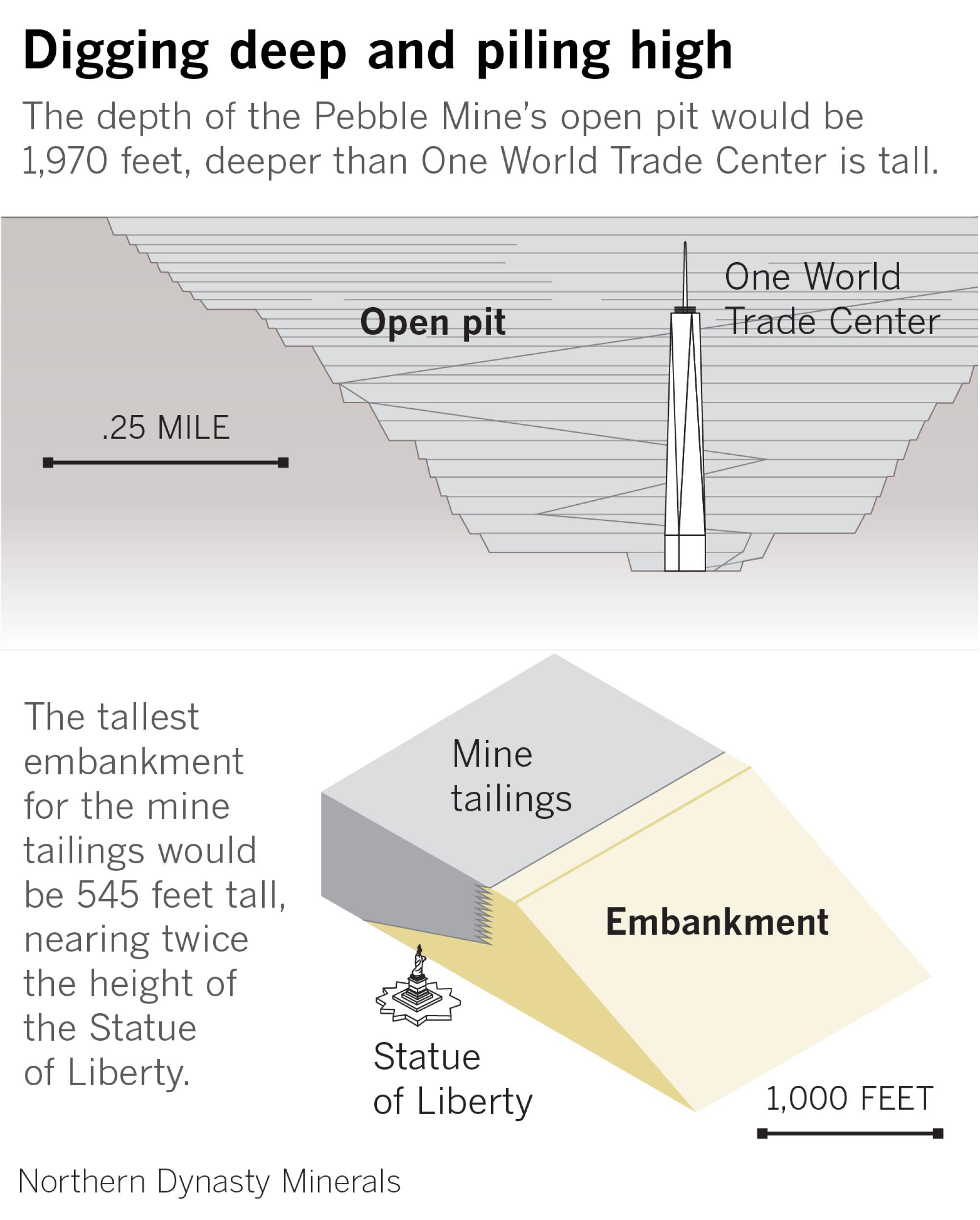

Weimer and Heatwole worked for Pebble Limited Partnership, a subsidiary of a Canadian company that aims to dig Pebble Mine, an open pit the size of 460 football fields and deeper than One World Trade Center is tall. To proponents, it’s a glittering prize that could yield sales of more than $1 billion a year in an initial two decades of mining.

It could also, critics fear, bring about the destruction of one of the world’s great fisheries.

Six weeks after that June 24 visit, Weimer, 31, would die when reportedly taking a single-engine plane through aggressive maneuvers in mountains near Anchorage. One of three other people killed in the fiery crash was the plane’s owner, Karl Erickson, who had directed Pebble’s safety operations and investigated aviation accidents.

The deaths of two members of the “Pebble family,” as company spokesman Heatwole termed it, were a reminder that technology is fallible and that best-laid plans can go awry.

The Pebble Mine site lies 200 miles southwest of Anchorage. One hundred miles farther southwest is Bristol Bay, home to the world’s largest run of wild sockeye salmon. Early each summer, hundreds of 32-foot commercial fishing boats surge into the bay, charging into state-designated territories like riders in the Oklahoma Land Rush. The fishery generates 14,000 jobs and $1.5 billion a year.

Captains and crews come from around the world to reel in as many tons of sockeye as they can during the lucrative two-month season. Regional tribal leader Robin Samuelsen Jr. worked the bay last summer for his 54th season, his four grandsons reeling in wildly wriggling fish.

“We have a gold mine,” he said. “It’s in salmon.”

Alaska has long been known for grand ventures and great risks. It’s also known for the richness of its natural resources, including gold, copper — and salmon.

In the case of the Pebble Mine, the question is: Can they coexist?

Geologists discovered and named the Pebble deposit 20 years ago. The resemblance that they fancied to California’s famed Pebble Beach golf links understates the wild beauty of the place, where rushing streams feed shimmering lakes in valleys of mossy tundra. Pebble Partnership’s corporate parent, Northern Dynasty Minerals, originally envisioned 78 years of mining, which would recover a little more than half of the mother lode.

In hopes of getting the initial phase past the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers for permitting under the Clean Water Act, the company scaled down its project to a 20-year mine that would still be colossal, with waste piles and other facilities occupying a site more than half the size of Manhattan.

Northern Dynasty’s plan leaves little margin for error.

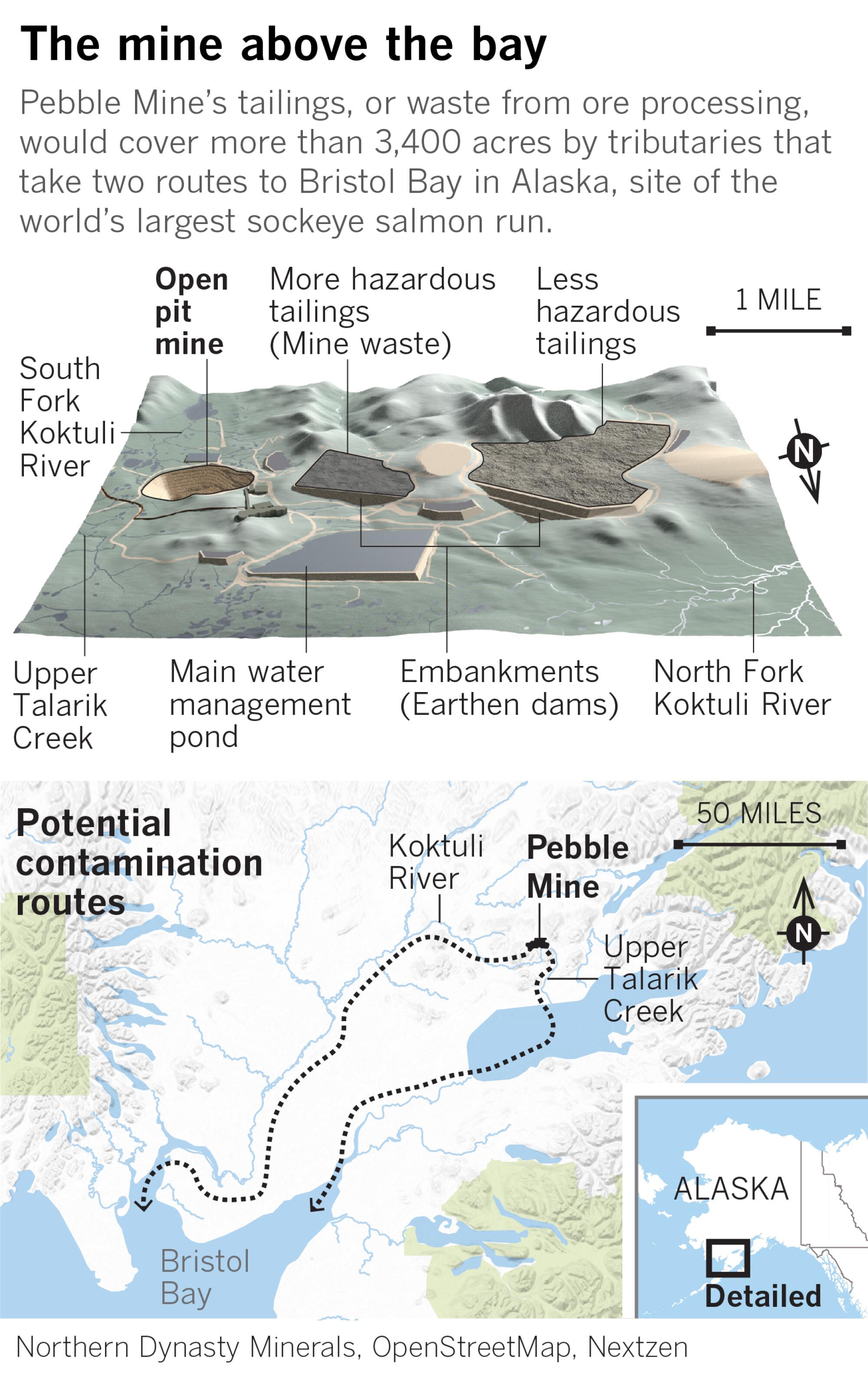

The development would destroy more than 3,400 acres of wetlands and 81 miles of streams. It would straddle Upper Talarik Creek and the Koktuli River, Bristol Bay tributaries known nationally for trophy trout fishing and salmon spawning.

Mineralized rock would be blasted in the pit, crushed, ground into sand, floated and concentrated, producing 180,000 tons of material a day. The challenge facing the company, in a place that averages more than 50 inches of rain a year, is how to ensure that tainted water would never reach Bristol Bay, which contains more than half the North Pacific’s sockeye salmon.

Northern Dynasty would submerge particularly hazardous mine tailings, piled across more than 1,000 acres, in water to prevent acid generation. This waste would be contained in liners behind earthen dams and ultimately dumped back into Pebble’s open pit after mining ended.

Less hazardous bulk tailings, heaped across 2,800 acres, would be held back by massive embankments designed to channel seepage into a treatment system. In all, these tailings dams, some as high as 40 stories, would extend more than 10 miles.

Company representatives say the bulk waste would have the consistency of inert sand. They say their latest plan would move most operations out of Upper Talarik Creek to reduce risks. But mine opponents say subterranean water systems are interconnected, and federal scientists say the latest groundwater models are inadequate.

The company plans to prevent contamination by treating as much as 13,000 gallons of discharge a minute on average from ore processing, tailings seepage and pit drainage, funneling it into the Koktuli River. The amount, which dwarfs quantities handled by other U.S. hard-rock mines, would increase to 22,000 gallons of water a minute after the mine closed. It would level out at 5,000 gallons a minute thereafter — perpetually, every day of the year, through storms, power outages and earthquakes.

In Bristol Bay, commercial, sport and subsistence fishermen worry about the dams, fearing they could breach or water treatment could fail. If so, contaminants in Upper Talarik Creek could spew into Iliamna Lake, Alaska’s biggest, and from there down the Kvichak River into the bay. Or toxins could enter the north and south forks of the Koktuli, flowing into the bay through two more rivers also legendary for salmon spawning.

And that isn’t the only concern.

Northern Dynasty proposes a 188-mile natural-gas pipeline across Cook Inlet to supply a power plant that could light up a city the size of Gary, Ind. An icebreaking ferry would carry ore 18 miles across Iliamna Lake, connecting to a haul road built through bear migration territory, and from there to a proposed seaport.

Pedro Bay, an Alaska Native community, is standing up to Pebble Mine developers, who wanted to put a road and pipeline through the remote village on a pristine lake

Ringed by snowcapped mountains, 80-mile-long Iliamna Lake is so pure that it needs no filtration for drinking. Its shores are dotted by half a dozen Alaska Native villages accessible only by boat or plane. The lake is home to sockeye and king salmon, and rainbow trout more than 28 inches long.

Environmentalists worry that the ferry and industrial activity could harm a rare species of freshwater seal inhabiting the lake. Village residents say the ferry would sever the thick ice they depend on as a winter roadway.

Priceless way of life

Yupik Eskimo children steer skiffs in swift current where the lake empties into the Kvichak River, fishing alongside bald eagles that pluck salmon from crystal clear pools. Moose and bear wander past a Russian Orthodox church in Igiugig, their community of 70 off the grid.

AlexAnna Salmon, the village tribal president, opposes Pebble Mine for its risks to fish and the development it would bring. “The way of life we have here is priceless,” said Salmon, whose tribal corporation refuses to sell the mining company rights of way for roads and a port. “It’s just a really hard concept for anybody to understand, but we can’t be bought off.”

On the northern side of the lake last summer, Jim Lamont fished an indigenous claim, stringing “set net” buoys perpendicular from shore. He sliced fresh-caught salmon at a backyard table in Newhalen, a struggling village made up of “HUD huts,” built with U.S. Housing and Urban Development money.

For years as Pebble Partnership drilled core samples, Lamont drove a bus for the company. He used to support the mine for the jobs it would bring. But the 71-year-old Vietnam veteran worries about impacts on salmon, which he hangs in neat rows like laundry on poles by his rusting backyard smokehouse.

“It’ll create jobs at the beginning,” he said, “and then once they start digging, it’ll be all technical people.”

Tom Collier, Pebble Partnership chief executive officer, sat at the head of an Anchorage conference table, sporting a blazer and faded jeans that he favors over suits he wore as a Washington, D.C., attorney. He said the mine as currently proposed was much smaller than previous versions, targeting only 10% of the deposit, and redesigned to “take all of the significant risk out of the project.”

As chief of staff to Clinton administration Interior Secretary Bruce Babbitt, Collier crafted protections for the northern spotted owl and old-growth forests. He stands to receive a $12.5-million bonus if the Army Corps of Engineers issues a permit.

“The notion that you have to choose between development and the environment is false: You can do both,” Collier said. He said the area around Iliamna Lake badly needed the jobs that the mine would bring — 2,000 during construction and 850 during operation. Northern Dynasty and former partners have spent $1 billion on exploration and lobbying.

Babbitt, a Democrat, signed a full-page newspaper advertisement in May opposing the mine with three former Cabinet members of Republican administrations. He said in an interview that open-pit mines were inherently risky, and the site championed by his former right-hand man was no place to put one.

“With the greatest fishery resource and sockeye salmon run in the world, you can’t take any risk,” Babbitt said. “That landscape is like a giant sponge soaking up 4 feet of rainfall a year and discharging it into wetlands, and it is impossible to say that you can treat that safely.”

Environmental geologist and consultant Richard Borden agrees, based on 23 years at Rio Tinto, one of four mining giants that have walked away over the years from Pebble ownership stakes. He believes that Pebble has designed a “Trojan horse” mine too small to be profitable, and intends to expand it after getting the initial permit — a charge that Collier denies.

Pebble has yet to provide an economic feasibility analysis, one of several documents absent from the Army Corps of Engineers’ draft environmental impact statement, which received more than 100,000 public comments by a July 1 deadline. In its review, the Interior Department departed from Trump administration doctrine, excoriating the corps’ 1,400-page statement as “so inadequate that it precludes meaningful analysis.” The agency called for a do-over.

David Hobbie, the corps official running the process, defended the impact statement and denied mine opponents’ contentions that he’s rushing on White House orders to issue a permit before President Trump’s term ends. The corps hopes to issue a final environmental impact statement early next year and decide next summer whether to let Pebble proceed.

The corps chose not to examine what would happen if a dam holding back the mine tailings were to fail. It found that scenario extremely unlikely. But critics point to breaches at other open-pit mines, including a collapse at Canada’s Mount Polley mine in 2014, when 840 million cubic feet of hazardous tailings surged into salmon spawning grounds.

A study commissioned by the Nature Conservancy found that a breach on that scale at Pebble was not far-fetched, and could be catastrophic to salmon habitat. Below Mount Polley, salmon returns have not significantly declined, but researchers are watching for effects of fish-eating organisms that ingest copper from the sunken tailings.

No one has studied Pebble Mine more thoroughly than scientists at the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, whose Seattle branch spent three years examining the issue and concluded in 2014 that the mine could cause “unacceptable adverse effects.”

Chris Hladick, EPA regional administrator in Seattle, sent a 100-page critique to the corps on July 1, saying the draft probably underestimated the potential harm to water quality and fish resources. He warned that mine waste could discharge far more water than predicted, affecting a larger area, and suggested lining the bulk tailings to avoid contaminating groundwater.

But a month later, after Alaska Gov. Mike Dunleavy lobbied Trump, Hladick followed instructions from EPA headquarters and withdrew the agency’s long-standing option to veto Pebble. The environmental organization Earthworks has sent the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission evidence of potential insider trading ahead of the agency’s reversal, which sent Northern Dynasty’s shares soaring.

In Bristol Bay, the EPA’s turnaround stung. Fishermen knew Hladick as a former city manager of Dillingham, the bay’s commercial fishing hub. He’s no longer welcome on many of their boats.

Opposition to the mine has united players often at odds, including Alaska Native communities and corporations, conservationists, sport fishermen and hunters. Several organizations sued the EPA this month calling for its reversal. On Wednesday, U.S. House Democrats opposing the mine argued with Republicans during a congressional committee hearing on Capitol Hill.

As the mining controversy captures national attention, it also divides families near the site.

In Iliamna village on the lake’s north shore, Steve Reimers parked his pickup by his mother-in-law’s smokehouse one summer day, and barricaded a gravel road to prevent passing cars from spreading dust on her fish.

The move was the latest by the head of the village’s Native corporation to annoy neighbors, some of whom resented him for entering an agreement allowing Pebble to build a ferry landing on the local company’s land. Cars soon broke through the tape that Reimers strung between concrete barriers.

Reimers dreams of starting multimillion-dollar businesses if the mine takes off. His extended family fractures along pro- and anti-Pebble lines. Myrtle Anelon, his wife’s mother, has lost count of her great-grandchildren, at 30-something. But she knows how she feels about the mine.

“People need jobs,” Anelon said, noting family members who sold their commercial fishing permits to pay bills. “Lots of people have moved out of the villages, and it’s sad, because they don’t know how to live in cities.”

Her son Tim Anelon, Reimers’ brother-in-law, uses his permit as a commercial fisherman, and opposes the mine. Anelon siblings have fought one another in the courts for five years, with allegations of fraud, trespassing and breach of contract. “There’s times we don’t talk to each other, maybe even for years,” Tim Anelon said.

Risking the future

As fog lifted one morning in July, Iliamna-based outdoor guide Jerry Jacques fueled his canary yellow Super Cub and took off south across the cobalt blue lake. From 2,000 feet, Jacques, 62, gazed clear to the bottom of fir-fringed island bays.

On the lake’s far side, Jacques passed above rolling tundra, shimmering lakes and meandering rivers, tracing the route that Pebble’s ore road would take through untouched wilderness. To the east was Katmai National Park and Preserve, where 13,000 visitors a year land in float planes to watch brown bears grab salmon that jump roaring Brooks Falls.

Ahead, snow-clad, steaming Augustine volcano soared 4,100 feet out of the sea. Jacques banked left and swooped over Bruin Bay. Below, dozens of brown bears dug clams, ate sedge grass and loped across tidal flats, ready for chum salmon to arrive.

For years, Jacques tried to stay neutral on Pebble. Then he looked closely at the science. He studied the probabilities.

“Where’s the incentive to keep treating that water for 400 years, let alone forever?” he asked. “What we do now is going to have an effect, within my grandchildren’s lifetime, on a major food source for the United States and the world.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.