Filmmaker Nobuhiko Obayashi, who portrayed war’s horrors, dies at 82

- Share via

TOKYO — Nobuhiko Obayashi, one of Japan’s most prolific filmmakers who devoted his works to depicting war’s horrors and singing the eternal power of movies, has died. He was 82.

The official site for his latest film, “Labyrinth of Cinema,” said Obayashi died late Friday.

Obayashi was diagnosed with terminal cancer in 2016 and was told he had just a few months. But he continued working, appearing frail and often in a wheelchair.

“Labyrinth of Cinema” had been scheduled to be released in Japan on the day of his death. The date has been pushed back because of the coronavirus pandemic, which has closed theaters.

“Director Obayashi fought his sickness to the day of the scheduled release of his film. Rest in peace, director Obayashi, you who loved films so much you kept on making them,” the announcement said.

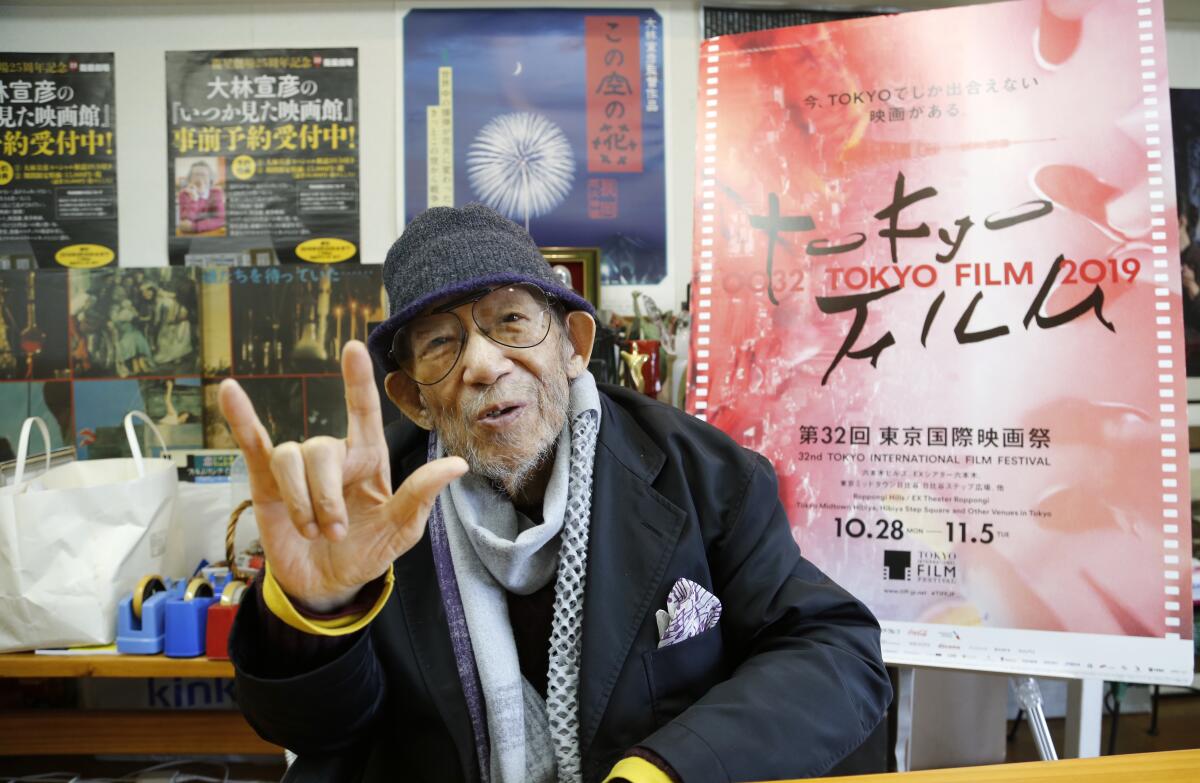

The movie was showcased last year at the Tokyo International Film Festival, which honored him as a “cinematic magician” and which screened several of his other works.

Obayashi stayed stubbornly true to his core pacifist message through more than 40 movies and thousands of TV shows, commercials and other video.

His films have kaleidoscopic, fairy tale-like imagery repeating his trademark motifs of colorful Japanese festivals, dripping blood, marching doll-like soldiers, shooting stars and winding cobblestone roads.

“Labyrinth of Cinema” is an homage to filmmaking. Its main characters, young Japanese men who go to an old movie theater but increasingly get sucked into crises, have names emulating Obayashi’s favorite cinematic giants, François Truffaut, Mario Bava and Don Siegel.

Obayashi’s “Miss Lonely,” released in 1985, was shot in seaside Onomichi, the picturesque town in Hiroshima prefecture where Obayashi grew up and made animation clips by hand.

His other popular films include his 1977 “House,” a horror comedy about youngsters who amble into a haunted house, and “Hanagatami,” released in 2017, another take on his perennial themes of young love and the injustices of war that unfolds in iridescent hues.

Obayashi was a trailblazer in the world of Japanese TV commercials, hiring foreign movie stars like Catherine Deneuve and Charles Bronson, highlighted in his slick film work that seemed to symbolize Japan’s postwar modernization.

He was born in 1938, and his childhood overlapped with World War II, years remembered for Japan’s aggression and atrocities against its neighbors but also a period during which Japanese people suffered hunger, abuse and mass deaths. His pacifist beliefs were reinforced by his father, an army doctor, who also gave him his first 8-millimeter camera.

His works lack Hollywood’s action-packed plots and neat finales. Instead, they appear to start from nowhere and end, then start up again, weaving in and out of scenes, often traveling in time.

During an Associated Press interview in 2019, Obayashi stressed his belief in the power of movies. Films like his, he said, ask that important question: Where do you stand?

“Movies are not weak,” he said, looking offended at such an idea. “Movies express freedom.”

He said then he was working on another film, while acknowledging he was aware of the limitations of his health, all the work taking longer.

At the end of the interview, he said he wanted to demonstrate his lifetime goal for his filmmaking. He showed his hand, three fingers held up in the sign language of “I love you.”

“Let’s value freedom with all our might. Let’s have no lies,” said Obayashi.

Obayashi is survived by his wife, Kyoko Obayashi, an actress and film producer, and their daughter, Chigumi, an actress.

A ceremony to mourn his death was being planned, according to Japanese media, but details were not immediately available. The Tokyo city and central government have requested that public gatherings are avoided because of the pandemic.

___

Yuri Kageyama on Twitter at https://twitter.com/yurikageyama

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.