- Share via

SIOUX FALLS, S.D. — The sun was barely up when Yvette Nimenya kissed her three boys, stumbled downstairs and ran out the door once again for the big brick building on North Weber Avenue.

She said “no” when the guard asked if she was sick before scanning her temperature. She grabbed a mask and face shield, slipped on her white smock and hard hat and walked onto the floor of Department 19. She stood for hours within arm’s length of dozens other immigrants separated by Plexiglas, stretching polyester nets over metal tubes as they were stuffed with 18-pound hams — thousands of times a day.

“It’s still not safe,” said Nimenya, whom bosses had sent home from the Smithfield pork factory in April after a co-worker became ill — among at least 900 to catch the coronavirus in one of the worst single U.S. outbreaks. “But we have no choice. We have bills. Anybody can get sick. Including me.”

Smithfield, a sprawling plant that until recently produced 5% of the nation’s pork, was among the first hit by the virus that has now crippled dozens of American meat producers. When it closed, grocery stores upped prices and rationed bacon. Farmers resorted to killing livestock. President Trump declared meat factories as “critical infrastructure” to stem more shutdowns that nevertheless continued as the virus tore through cutting floors.

Workers now trickle back through factory gates in this region of hog farms, where the paychecks of meat workers are the lifeblood of the economy. And they face an acute version of the life-and-death calculus confronting every American: What’s safe, and for whom?

“Americans eat all kinds of food,” Nimenya, a 32-year-old Burundian refugee, recently said as she held her toddler in her sparse apartment on the southeastern edge of the city, where colorful East African straw mats covered the floors and rainbow plastic garlands were nailed to the walls. “Why is pork essential?”

Pork is part of life here.

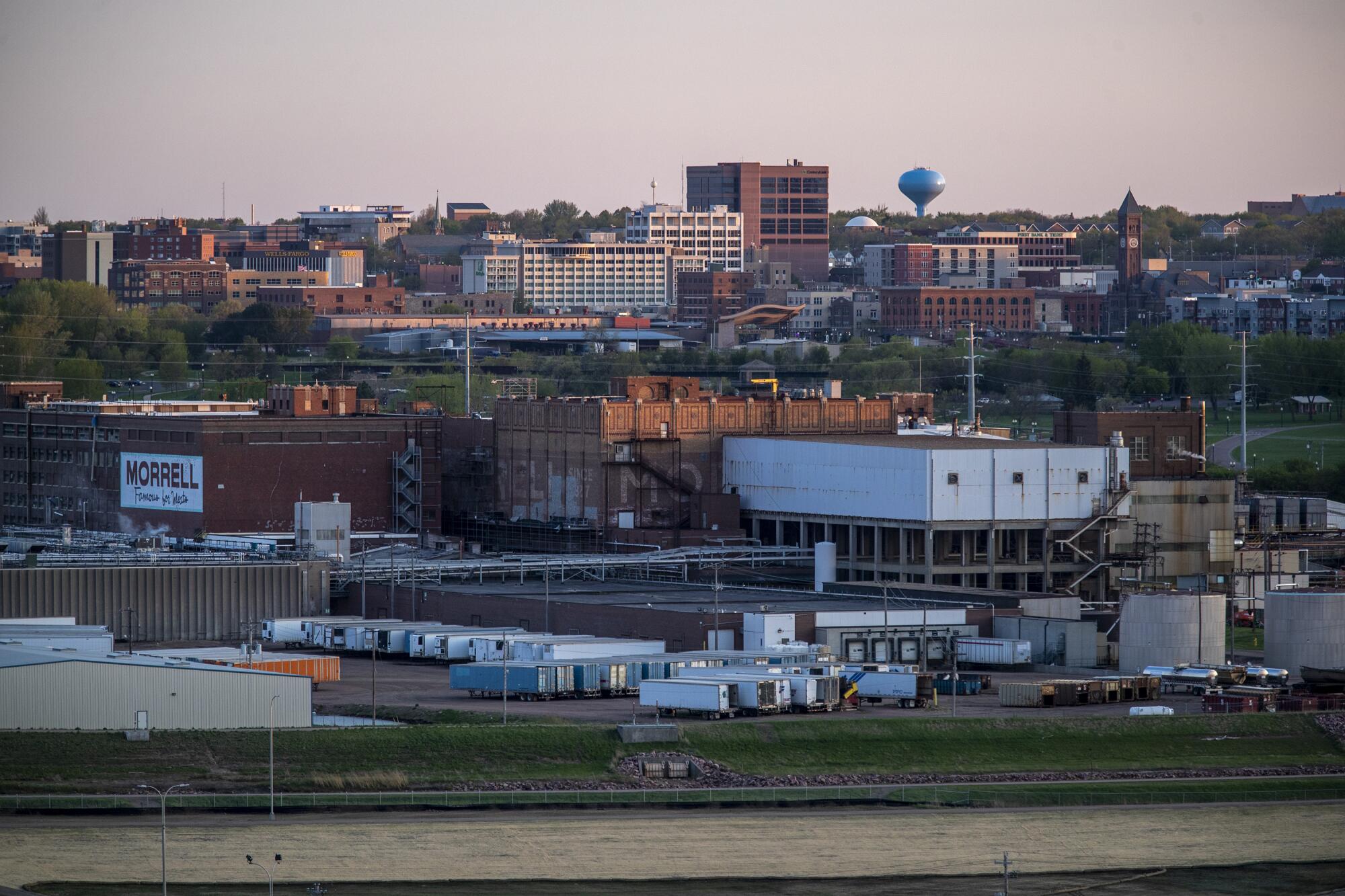

A community of 188,000, Sioux Falls straddles the Big Sioux River, which curves around the plant’s 45-acre property. More than 40 times smaller than the U.S. epicenter of New York, this is South Dakota’s largest city, founded in 1856 by land speculators and settled before them by Dakota and Lakota tribes.

Its downtown of bars and eateries doesn’t stretch beyond 10 blocks. Victorian-era houses on grassy plots spread out in adjacent neighborhoods. The Catholic cathedral’s bell towers stand out on the low-hung skyline in a land where residents tend to stay home through the bitter, long winters. A 15-minute drive leads past semi-truck and tractor lots to wide-open vistas of just-planted soy and corn fields.

Yet of the more than 5,000 cases that have hit South Dakota, close to three-quarters are in Sioux Falls. A state with America’s fifth-smallest population, it has had more infections per capita than all but the largest dozen. The biggest cluster has been traced to Smithfield, where 3,800 workers speaking 80 languages crammed into eight floors processing 19,000 pigs a day before the virus shattered the immigrants who dominate the rolls.

Two workers died. Augustín Rodriguez, 64, died of the virus after nearly two decades cutting pork. Craig Franken, 61, was planning his retirement after 40 years on the job.

Many more were hospitalized. Most suffered quietly at home, becoming pariahs in their adopted city as the toll of the virus reached far beyond the infected.

“If you were out and people found out you were from Smithfield, they would just run away from you,” said Nimenya, who admitted to avoiding certain co-workers when she first heard murmurs of the virus’ spread inside the plant’s gates.

Stores posted signs banning pork workers. Uber drivers rejected rides to the factory. The governor blamed crammed housing among immigrants for the spread. A corporate spokesperson said “living circumstances in certain cultures” were the culprit. The building stayed open as infections multiplied, only to close after protests went viral and the mayor and governor called for a shutdown.

“It swept like a plague through the community — it still is,” said the Rev. Kristopher Cowles of Our Lady of Guadalupe, a Catholic parish. Employees of Smithfield from Guatemala, El Salvador and Mexico make up a third of the congregation at the church, the only one in the city for Spanish-speaking Catholics. Church is now open again, but most of congregants haven’t returned, fearing they will scare away others or get reinfected.

In a city where 82% of residents are white, the outbreak, as it has done in towns across America, has highlighted cultural divides. The mud-booted farmer on the outskirts doesn’t often mingle with the darker-skinned workers whose hands transform the hogs he raises into the neatly packaged cuts on supermarket shelves. But they are connected, even if the numbers behind the virus show the disparity of their lives, histories and beliefs.

The majority of those who get infected are racial minorities. At rowdy bars, now reopened, customers down pints and servers take orders with no masks, while crowds jam into Hy-Vee grocery stores on weekends. The city just lifted all restrictions on capacity inside businesses. Yet the small African, Asian and Latino markets on the east side, where most immigrants live, are still the realm of social distancing with floor stickers to mark where to stand and N95 respirators that abound.

Nimenya was born in Rwanda to parents who fled civil war in Burundi. She grew up in a Tanzania refugee camp, where the family settled after the Rwandan war broke out 1994. They came as refugees to Tucson on July 20, 2007.

Mom took up a job working as a dishwasher at a nursing home, as did Nimenya. Dad worked at a restaurant.

In Tucson, she met Jeremie Nimpaye, a Burundian refugee who boarded a bus for Sioux Falls after hearing of Smithfield’s unionized jobs — where workers made $25 an hour in overtime and had health insurance. Two years later, they married.

She was surprised to meet more Burundians in her new city than she’d ever seen in Arizona. The dry, freezing winters were as foreign as the distinct, pink Sioux quartzite that made up old buildings across the city. She quickly noticed that many of the East Africans she met gathered each day on North Weber Avenue.

Smithfield offered Nimenya a job on Aug. 8, 2011.

Workers labored side-to-side, back-to-front in a refrigerated warehouse where they would ask for bathroom breaks just to warm up. Nimpaye worked the night shift deboning slabs of shoulder. She did days. Their hands ached from the repetitive motions; their clothes sometimes smelled of dried blood and meat. They hardly saw each other as three boys, the oldest now 10, were born. Nimenya once sued the company, saying racist managers sexually harassed her, before losing in court.

But at more than $17 an hour before frequent overtime, it was all worth it. The couple could afford a babysitter, two used cars, a Roku and still cover $995 per month for their three-bedroom rental. They had cash to spare for parents and relatives in East Africa.

“I came from a continent where everybody knew about America and the life there,” said Nimenya, who speaks softly and grew accustomed to wearing jeans and a T-shirt every day while out of work. “Now, I was living in America and making good dollars.”

She proudly kept a locker room selfie showing her all-white Smithfield attire on her phone, which had a plastic case printed with the green, white and red Burundian flag.

Rumors of the virus hit the factory in March. By mid-April, managers sent employees home with 40 hours of weekly pay but no overtime. A high school parking lot in a neighborhood popular with African migrants opened in May to test workers. Thousands showed up despite no requirement to get results to go back to work.

Nimenya defended her decision not to get tested, saying she didn’t feel sick. But she also felt the danger lurking.

“If I could find another job now, I would take it like that,” she said on a recent afternoon after being back on the floor. “But with the coronavirus, are there jobs anymore?”

She complained of the new mask and shield that made it hard to breathe. She worried the new, shorter shifts — some just five hours — would become permanent after bosses told her there wasn’t enough meat. For now, she’d still get paid each week for 40, and get an extra $200 for returning to the job.

Forty miles southwest of the factory, where the highway gives way to dirt roads and silos, the shutdown has trickled to family-run hog farms that supply Smithfield. The scent of pig manure fills the air. But the rumble of livestock trucks that once rolled in and out of barns has slowed.

The great-grandson of Danish and Swedish immigrants, Craig Anderson was born into a family of farmers on the edge of Centerville, a town of 800 established on the banks of the Vermillion River just years after Sioux Falls came to exist.

His father helped launch the local pork producers association. His mother was president of the South Dakota Porkettes.

In this 98% white city dominated by farming families and their kids, Anderson graduated from the sole public school before studying agriculture at South Dakota State University. He met his wife, Gail, whose parents raised pigs and grain one town over, after an introduction through relatives.

“I’ve never had a job outside this farm,” said Anderson, who keeps a trim white beard, doesn’t like to leave the house without his bullhorn-embroidered cap, and speaks with a slight drawl.

Now 51, he lives on the same property where his forefathers once toiled, in a house his parents built where plates with hog prints decorate the walls next to framed aerial shots of two barns he runs with his two sons and daughter. Together, they house 2,400 pigs.

Before the plant closed, the days were routine and predictable. Now, with the factory still below full speed, he doesn’t know what comes next.

“We used to have a reliable schedule,” said Anderson, who sells off his animals at least twice each year, including once in the spring. “Now, anybody’s guess is as good as mine as to when the hogs will go.”

It takes up to five months to get his pigs, raised on corn and soybean meal, to a sellable weight between 270 and 300 pounds. Over the years, the same animals have at times probably fallen beneath Nimpaye’s knife and been pressed into Nimenya’s nets.

But with fewer orders, some now approach 350 pounds, bringing a new set of problems. Anderson worries about pushing legal limits on how many he can keep in one space. Their bodies are growing far outside the window that pork producers, whose factories are tailor-made for smaller carcasses, will buy. And he long ago signed a contract for upcoming deliveries of piglets that will soon be on their way.

He’s changed the feed, replacing soybean meal with oats so the animals grow more slowly on a diet high in fiber and low on protein. Recently, he resorted to selling a few individual hogs to neighbors. It was a novel idea for a man whose family has depended on its relationship to the plant since it was John Morrell, the name long before it was purchased by Virginia-based Smithfield, now part of a Chinese conglomerate.

“A complete loss, no profit at all,” he said of the $125-a-head price. He looked across the soy and corn fields on his 640 acres, crops he wouldn’t harvest until months later.

He prayed for a return to normal.

“We’re farmers. We plant, we feed, and we trust God to give us in return,” Anderson said.

He also prayed for the workers at the factory, a place where he once knew many of the men on the floor before they retired and influxes of immigration — first from Mexico and Central America and later from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Sudan and Ethiopia — changed its makeup over the decades.

“I’m concerned about the workers. I am. But it doesn’t make our situation any better,” Anderson said. “As for the plant itself, it’s safe. But if you put that many people together, things are bound to happen.”

Even with the large toll of the virus, most at Smithfield didn’t get sick. Some believe the danger was exaggerated.

“I don’t worry about this at all. There is no panic,” said Svitlana Pavlus, a 24-year-old Ukrainian refugee who began working there last year after arriving in the city two years ago.

An operator, she makes sure bags of ground pork that ride along the line are properly boxed by robots. “In my department, I do not know a single person who got this virus,” Pavlus said, describing the reports as overblown.

John Massaley, a 51-year-old Liberian refugee in Department 19, said people “were right to get worried and scared.” But he was assured with precautions now in place.

A former overnight stockyard worker, he collects, weighs and tags hams before pushing them into an industrial cooler.

“I don’t stay in one place. I’m always moving around,” said Massaley, who returned to work after getting the nasal test. “Being close to people is not a problem then.”

“Washing your hands. Covering your face. We’ve got to be very sensitive and follow procedures, but as long as you do we’ll be OK,” he said.

On a recent morning, the city’s rhythms returned. The vast dirt lots outside Smithfield again began to fill with cars, and the smell of hogs returned to the air as livestock trucks rolled by.

The mayor of Sioux Falls stood outside the brick building on North Weber Avenue. and cheered as masked workers switched shifts. Advertised as a “parade” to honor the factory’s refugees, about a dozen people — nearly all white — showed up as they held red, white and blue “thank you” signs.

Nimenya passed by them, confused, as she entered the property. She wondered if they were homeless before noticing the words “thank you” and “Smithfield.” She smiled in appreciation. She also wondered how people had found the time to show up. As she told the guard she was healthy and did a temperature check, she mused over what kind of jobs those outside the gate had.

“To be American is to work. I’m not saying I won’t,” she said. “But why do some people get to stay home, and others are pushed to return?”

Times staff writer Arit John contributed reporting.

(This is the first in a series of occasional stories on the coronavirus’ effect on the Sioux Falls Smithfield plant and its workers.)

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.