Guilty, your virtual honor: Texas court holds jury trial over Zoom

- Share via

DALLAS — The jurors appeared on screen from their living rooms, bedrooms and home offices. Juror 11 took notes as a sheriff’s deputy testified about giving a speeding ticket. Juror 18 occasionally looked away as a white cat scampered across her couch.

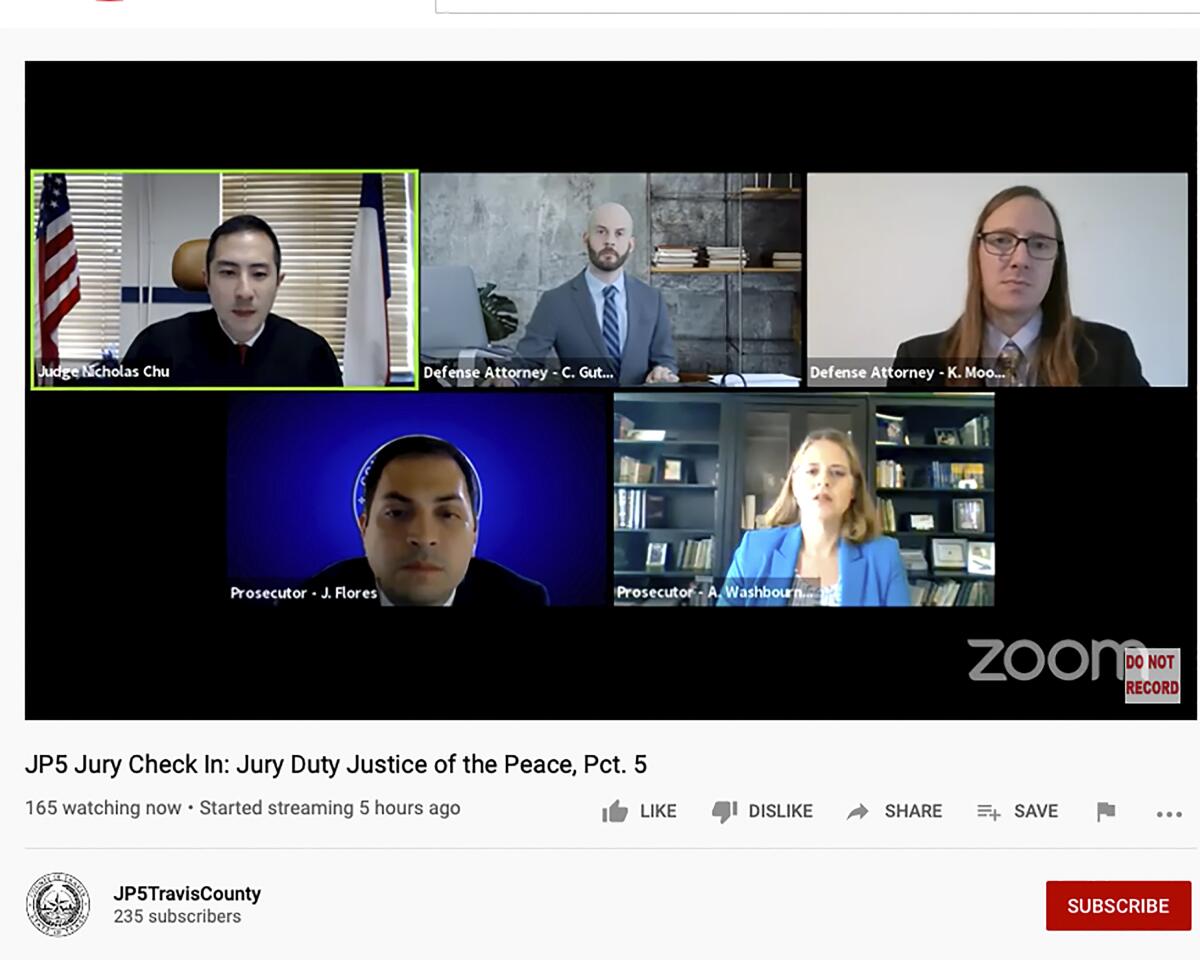

They gathered on a video conference call Tuesday in what Texas court officials said is a national first: a virtual jury trial in a criminal case.

“You’re here today for jury duty in a different way,” Judge Nicholas Chu said at the start of the trial. “That’s jury duty by Zoom.”

The Travis County misdemeanor traffic case is the latest experiment in how to resume jury proceedings in a criminal justice system that’s been crippled by the COVID-19 pandemic. It was greeted by lawyers and legal experts as a low-risk step forward, but one that could imperil defendants’ rights.

Nationwide, the virus has put many court cases on indefinite hold and left some defendants in jail longer, possibly exposing them to outbreaks. It has forced judges to hold hearings via video conference and even led the Supreme Court to hold oral arguments by phone for the first time in its history.

In Texas, fewer than 10 jury trials have been held since state courts resumed in-person proceedings in June, according to Megan LaVoie, a spokeswoman for the state judicial branch. She said Tuesday’s case was picked as the first criminal jury trial to be held virtually in the U.S. because both sides agreed and it was “ready to go.”

An online bond hearing for a Florida teen accused of hacking prominent Twitter accounts was interrupted by rap music and pornographic videos from users who apparently disguised their names

The trial of Calli Kornblau, an Austin-area nurse charged with speeding in a construction zone, was broadcast live on YouTube. At some points, there were more than 1,000 people tuned in to hear testimony about traffic rules and the workings of police laser speed readers.

Chu cautioned the jurors that the unusual setting made their work no less serious, warned them against using Google to search about the case and forbade them from posting about it on social media. He asked for their patience with technological “hiccups” and apologized for the proceeding taking much longer than expected.

Shortly before 5 p.m., the lawyers finished their arguments and the jury was sent to a private virtual room where they could look at the evidence and deliberate. They took about 30 minutes to return a guilty verdict. Kornblau was given a deferred adjudication, and ordered to pay a $50 fine and court costs.

Her case comes after another Texas court held an experimental civil jury trial in May.

Singapore has sentenced a drug suspect to death at a hearing held on the videoconferencing app Zoom because of the city-state’s coronavirus lockdown.

Defense attorneys have raised constitutional and logistical concerns about e-court for criminal cases, saying they already struggle to speak privately with their clients during routine hearings held remotely.

Legal experts say the pandemic requires courts to strike a tricky balance: They must advance cases to give people speedy trials and prevent an overwhelming backlog while preserving defendants’ rights.

Whether trial by Zoom can achieve this equilibrium is unclear.

Daniel Medwed, a professor at Northeastern University School of Law, said one concern is that video won’t allow jurors to assess witness credibility through demeanor and body language. Another is that it falls short of the constitutional guarantee that defendants can confront witnesses.

There are also questions about whether the lack of physical gathering fundamentally changes the nature of jury deliberation. And a conviction through such a trial might run into trouble on appeal, said Laurie Levenson, a professor at Loyola Law School and former federal prosecutor.

“It’s a grand experiment,” said Levenson. “Whether or not it will comply with the Constitution still remains to be seen.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.