Ordered to stop, census takers fall short of target goal in some areas of the U.S.

- Share via

ORLANDO, Fla. — From tribal lands in Arizona and New Mexico to storm-battered Louisiana, door-to-door census workers were unable to reach all the households they needed for a complete tally of the U.S. population, a count that ended abruptly last week after a Supreme Court ruling.

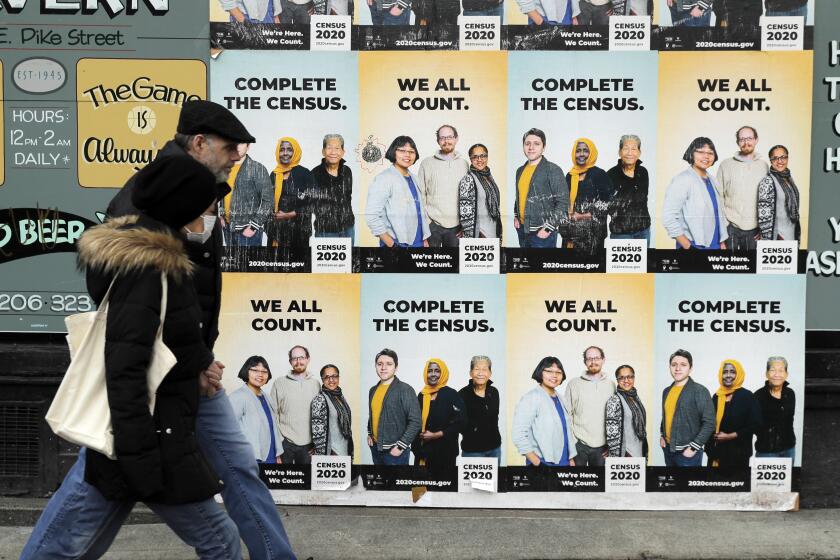

Community activists, statisticians and civil rights groups say racial and ethnic minorities are historically undercounted, and shortcomings in the 2020 census could set the course of life in their communities for years to come.

The count determines the number of congressional seats each state gets, where roads and bridges are built, how schools and healthcare facilities are funded and how $1.5 trillion in federal resources is allocated annually.

“An undercount in our community means schools are overcrowded, hospitals are overcrowded, roads are congested,” said John Yang, president and executive director of Asian Americans Advancing Justice.

The census ended last week after the Supreme Court sided with the Trump administration and suspended a lower court order allowing the head count to continue through Oct. 31.

The U.S. Census Bureau says that overall, it reached more than 99.9% of the nation’s households, but in a nation of 330 million people, the remaining 0.1% represents hundreds of thousands of uncounted residents. And in small cities, even handfuls of undercounted residents can make a big difference in the resources the communities receive and the power they wield.

A census tract in Stockton is the hardest to count in California, emblematic of the challenges faced by other underserved communities in the state.

Also, a high percentage of households reached does not necessarily translate to an accurate count: The data’s quality depends on how they were obtained. The most accurate information comes from people who “self-respond” to the census questionnaire online, by phone or mail. Census officials say 67% of the people counted in the 2020 census responded that way.

In any case, census takers who go door to door fell short of the 99.9% benchmark in many pockets of the country.

In large parts of Louisiana, which was battered by two hurricanes, census takers didn’t even hit 94% of the households they needed to reach. In Window Rock, the capital of the Navajo Nation on the Arizona-New Mexico border, an area ravaged by COVID-19, census takers reached only 98.9%.

Other parts of the U.S. where the count fell short of 99.9% include Quincy, Mass.; New Haven, Conn.; Asheville, N.C.; Jackson, Miss.; Providence, R.I.; and Manhattan, where neighborhoods emptied out in the spring because of the coronavirus.

The U.S. Postal Service isn’t the only staid federal agency to be drawn into a political battle this year.

Rhode Island is one of about 10 states projected to lose a congressional seat, based on anticipated state population figures in the 2020 census. It could take as few as 30,000 overlooked people for the nation’s physically smallest state to revert back to having a single House district, said John Marion, executive director of Common Cause Rhode Island, a nonprofit watchdog.

The early conclusion of the census “is really going to stymie our efforts, not only to maintain that second district but also to have fair representation in our state Legislature,” Marion said.

Jackson Mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba blamed the pandemic for curtailing in-person outreach efforts that could have made a difference in harder-to-reach neighborhoods. The mayor wasn’t sure having an extra two weeks would have made a huge difference, but he said not having a complete count is significant: Jackson loses $1,000 each year for every person not counted.

“All of this has long-term implications for city planning, for how we address our needs and for ensuring that we are fairly represented in the statehouse and in Congress,” Lumumba said.

There are also concerns about the quality of the data obtained. The second-most accurate information after self-responses comes from household members being interviewed by census takers. When census takers can’t reach someone at home, they turn to less accurate information from neighbors, landlords and administrative records. Information was obtained by these methods for almost 40% of the door-knocking census takers’ caseload, according to the Census Bureau.

“Do not be fooled by the Census Bureau’s 99% myth. If there was ever fake news, this is it,” said Marc Morial, president and CEO of the National Urban League, one of the civil rights groups that challenged the Trump administration’s census schedule in court.

Census Bureau Director Steven Dillingham said Monday that a first look at the data collection operation indicates “an extremely successful execution.” He noted that the 67% self-response rate this year was higher than the 66.5% reached during the 2010 census.

How much time the Census Bureau has to crunch the numbers is still being fought in courts and in Congress. Civil rights groups and others are pushing Congress to extend the bureau’s deadline for turning in apportionment numbers for congressional seats from Dec. 31 to the end of next April.

President Trump has swung a wrecking ball through the 2020 census in hopes of hurting Democrats and helping Republicans.

The Trump administration said the Census Bureau needed to end the count early to meet the Dec. 31 deadline. But top officials at the Census Bureau said as recently as July that it would still be impossible to process all of the data by the end of the year. They’ve since changed their tune, and on Wednesday they said in a conference call with news media that the deadline can be met by working around the clock and with technological advances in computer processing.

Groups suing the administration over the timetables said the deadline for turning in apportionment numbers was moved up to accommodate an order from President Trump to exclude people in the U.S. illegally from the numbers used to divvy up congressional seats among the states. Sticking to a Dec. 31 deadline ensures that data-processing remains under the administration’s control, regardless of who wins the presidential election.

A panel of federal judges in New York ruled that Trump’s order was unlawful, but the administration has appealed to the Supreme Court.

“This census isn’t over,” Morial said. “We will continue to fight in the courts, Congress and the court of public opinion.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.