This is what happens when a Buddhist nun joins a heavy metal band

- Share via

TAICHUNG, Taiwan — Five men walked onstage one Saturday night in January with electric guitars, and the audience anticipated one thing: ear-piercing riffs.

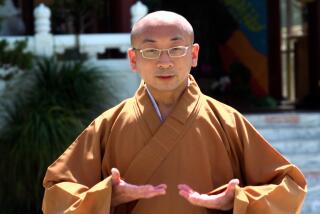

The black-clad members of a heavy metal band matched the color of the central Taiwan Legacy Taichung concert hall’s hulking amplifiers. But one member of the band stood out more than the others. Head shaved and dressed in her religion’s traditional orange robe, a Buddhist nun stood among them.

Miao Ben, 50, is a member of Dharma, a Taiwanese Buddhist heavy metal band. She’s quite a contrasting sight onstage alongside the other members of the band, some in goth makeup, Grim Reaper robes and fake blood. Unusual, to say the least.

“You really have to get your tongue ready to explain this fusion to traditional people,” said Miao Ben, who works by day for a Taiwanese Buddhist charity that helps children in Africa. “When I first heard heavy metal, I thought it was hard to accept, but after attending these concerts I’ve found it has a beautiful melody, and I was moved by the band’s passion.”

Dharma says its wall-splitting chords fit snugly with the religion, musically and spiritually, despite murmurs of opposition from Taiwan’s more traditional believers who prefer quiet chants in forested temples.

One recent evening, Miao Ben rang a ritual bell under the thunder of guitars so loud that several supporting nuns handed out earplugs to an audience of some 200 headbangers. Moments earlier, she had joined nine other nuns in opening the performance, reading a scripture before the three guitarists filed onto the stage.

Miao Ben says she met Taipei drumming instructor and band founder Jack Tung last year through a former classmate. She joined Dharma, which refers to the teaching of Buddhism, because she felt metal would link the faith to younger Taiwanese who might otherwise lack exposure besides memories of temple visits with their parents.

“We can gain their acceptance little by little,” she said.

In 2017, Tung started visiting as many of Taiwan’s 4,000 Buddhist organizations as he could, including the biggest four. The man with long black hair and specs wanted to make sure his plan to mix Buddhism with metal wouldn’t offend anyone. The singer will chant like monks and nuns, he would explain, and shun violent heavy metal themes.

“I was afraid they would think I was doing something incorrect or not good, yet when I ran into them again, they gave it their approval,” Tung said. “We pick chants with significance. We just have to be mean and use loud noise to scare off evil things.”

Tung said no organization opposed his blend of metal and mantras, though he encountered some individual Buddhists with doubts about whether the faith and the music genre fit spiritually. A representative for one landmark Taiwanese Buddhist group, Fo Guang Shan Monastery, declined to comment on Dharma.

Tung won a high school percussion contest at age 15, a jump-start to his music career. He’s been into metal for a couple of decades and teaches drums in his hometown, Taipei. He won’t disclose his age at the risk of surprising younger students.

All along, Tung said, he had always felt the pull to do something “alternative.” When he heard Tibetan Buddhist music 16 years ago, he knew that would eventually be his heavy metal mission. He assembled an equally enthusiastic band from Taiwan’s small metal scene.

Lead guitarist Andy Lin helps Tung compose the band’s songs, which total 12 and counting. He grew up going to Buddhist temples with a devout father who made him recite scriptures, an edge now in picking mantras that are ideal for song lyrics.

The band’s rhythm guitarist, Jon Chang, 36, applied to Tung for the job and brought to it a lust for metal that started in 1999 when he lived in Canada and first heard Metallica play on MTV. He works selling guitars for a music distributor in Taipei.

Lead singer Joe Henley, a 38-year-old Canadian, moved to Taiwan in 2005 on a college roommate’s advice and met the drummer-founder a year later. They still belong to two other, now dormant metal bands. Tung wanted to steer one of those bands toward Buddhism, Henley recalled, but other metal heavyweights in Taiwan preferred “straight-up, old-school, blood-and-guts death metal,” he said.

Henley joined partly to ease the stress of his other work, including finding jobs as a freelance writer for documentaries and magazines. While learning Dharma’s lyrics, the singer, who was “born Christian,” converted to Buddhism a year ago and now calls it a “refuge.”

About 8 million Taiwanese, or 35% of the population, are Buddhists, Taiwan Ministry of the Interior data show.

Henley studied four months with a monk to memorize the lyrics that are all in Sanskrit — Tung wants to stick with the original language for authenticity. “Thankfully it’s all mantras, so it’s usually quite short. I might be repeating the mantra 10 or 20 times over the course of the song,” Henley said.

Then there’s the one with 84 names in a row, with no rhyming. “I growl them,” he said backstage that Saturday at the Legacy Taichung concert hall.

Endless volumes of uncopyrighted scriptures catalyze the composition of songs. “We joke that we’ll never run out of lyrics because there are so many sutras we can choose from,” Chang said.

“Amitabha Pure Land Rebirth Mantra” is one of the sutras they use in song. Reciting it is supposed to bring peace and joy. Another is “Medicine Buddha Mantra,” which is supposed to bring healing and purification from bad karma.

Dharma first performed in October 2019, but gigs stalled early last year because of Taiwan’s curbs on large-scale events to prevent the spread of COVID-19. Since performances resumed last October, the band has taken the stage four times, and at least 200 people have turned out for each concert, with a record of 900.

There’s a curiosity factor because we have a monk in the band, so they stop by the stage, and hopefully they stay to enjoy the music too.

— Joe Henley, lead singer of Dharma

Band members expect a run of shows this year but haven’t come out with an album or turned a profit yet. They were excited to be the final and main act of four bands in Taichung on Jan. 2.

“There’s a curiosity factor because we have a monk in the band, so they stop by the stage, and hopefully they stay to enjoy the music too,” Henley said.

Fans were surprised.

“This is like two different concepts coming together,” Taiwanese computer industry worker Jeffrey Sho, 39, said after watching the $27-per-head concert. “This is pretty special for us to hear heavy metal mixed with something else. The nuns on stage, that intro, gave the whole act a good feeling.”

Younger Taiwanese are losing touch with Buddhism partly because of how it’s spread, said Lin Hung-chan, a publicity director with 55-year-old Taiwan-based Buddhist charity the Tzu Chi Foundation. Elders normally visit temples and watch Buddhist cable TV channels, both outside the scope of media and activities of most Taiwanese people under 40.

“Dissemination, after all, has many methods, and it’s not limited to a traditional method,” Lin said.

Buddhist chanting and heavy metal mix well from a musical perspective because both genres normally stay on the same key for a long time, said Freddy Lim, a Taiwanese metal band leader and member of the island’s parliament.

Sticking to a single key can make listeners feel at peace even if they start out angry, he said.

“For the band to mix Buddhist chants into metal I find quite skillful,” said Lim, who started the band Chthonic in 1995 and has heard Dharma on YouTube.

But Wen Chih-hao, 30, a fan from Taiwan’s information technology sector, left the Taichung concert early because he had been to temple gatherings before and found that scripture readings onstage clashed with the concert’s party atmosphere.

“I think the concept is OK, but when I hear Buddhist scriptures I get scared and don’t feel so playful,” Wen said once outside on the sidewalk.

Jennings is a Times special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.